What Does Paying 35% Tax Actually Get Us? A Mumbai Writer's Perspective

I remember the moment I knew I had to leave Mumbai: around 15 years ago, at the end of the monsoon season, the water flowing from my tap turned a deeply concerning shade of brown. A subsequent laboratory report confirmed my worst fears – it was contaminated with sewage. This was not an isolated incident affecting only my household. The actor Hrithik Roshan, who lived just down the road, made a similar complaint to the press around the same time.

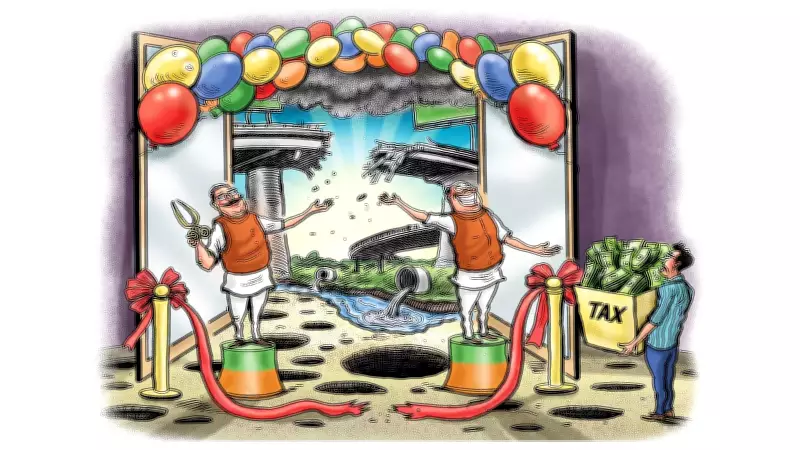

The Satirical Reality of Indian Democracy

This situation highlighted the true, almost satirical nature of Indian democracy at that moment. Here we were, a humble writer and a celebrated Bollywood superstar, both facing the same basic infrastructural failure. We were, to paraphrase an American president, essentially forced to eat shit. The irony was palpable and deeply frustrating.

Questioning the Returns on High Taxation

This personal experience forces a critical question that many middle and upper-class Indians grapple with: What does paying 35% tax actually get us? When citizens contribute a significant portion of their income to the state, there is a fundamental expectation of reliable public services in return. Basic amenities like clean, potable water are not luxuries; they are essential rights that taxation is meant to secure.

The incident in Mumbai underscores a broader issue across urban India. High tax brackets, like the 35% rate, are justified by the promise of developed infrastructure, efficient governance, and improved quality of life. Yet, stories of sewage mixing with drinking water reveal a stark disconnect between taxpayer contributions and on-ground realities.

A Shared Struggle Across Socioeconomic Lines

It is particularly telling that this problem did not discriminate based on fame or fortune. Both an ordinary writer and one of India's most bankable film stars were equally vulnerable. This shared struggle, while uniting in a perverse way, exposes systemic failures that affect all citizens, regardless of their social or economic status.

The memory of that brown water remains a powerful symbol. It represents not just a personal breaking point that led to leaving the city, but a larger, unanswered question about the social contract in India. When taxpayers fulfill their financial obligations, what tangible improvements can they rightfully expect in their daily lives? The search for that answer continues for millions.