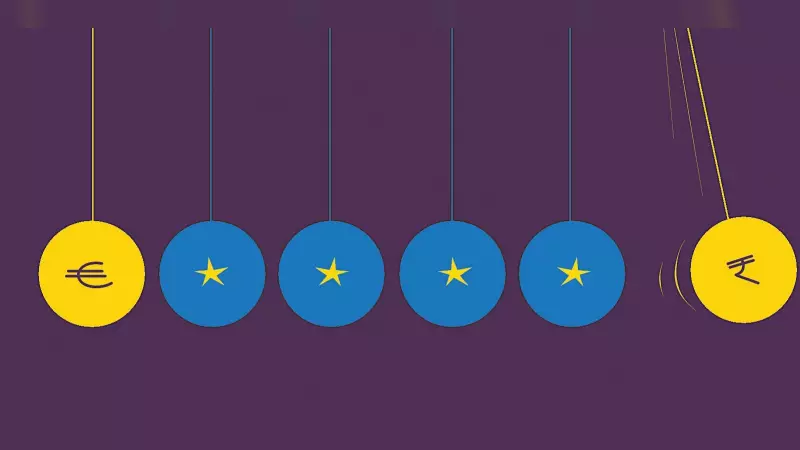

From the very first day of 2026, a significant financial challenge has emerged for Indian steel and aluminium producers selling to Europe. The European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has officially taken effect, imposing a tax on imports based on the carbon emissions generated during their manufacturing. This policy is set to reshape trade dynamics, potentially eroding a substantial portion of India's export revenue from a critical market.

The Direct Impact on Indian Exporters' Bottom Line

The financial strain imposed by CBAM is severe and immediate. Experts estimate the new carbon tax could wipe out 16 to 22 per cent of the actual prices received by Indian companies. This drastic cut in margins will force widespread renegotiation of existing contracts and significantly weaken the competitive position of Indian products within the EU. This is particularly alarming as the European market absorbs approximately 22 per cent of India's total steel and aluminium exports.

The warning signs were already visible. In the financial year 2025, India's exports of these metals to the EU stood at $5.8 billion, which was a notable 24 per cent decline from the previous year—and this was before the tax was formally applied. The drop began after the CBAM's transitional phase started in October 2023, requiring detailed plant-level emissions reporting. The burdens of compliance, data collection, and verification led many Indian firms to reduce their European shipments well in advance.

How CBAM Works and Why It's Costly for India

CBAM essentially extends the EU's internal carbon pricing rules to imports. Within Europe, companies pay for their emissions under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). CBAM imposes a comparable cost on foreign producers to prevent "carbon leakage," where companies might relocate production to regions with laxer climate regulations. The mechanism currently covers steel, aluminium, cement, fertilisers, electricity, and hydrogen, with plans to include more sectors.

The tax liability is calculated using two key factors: the volume of carbon emissions from production and the prevailing EU carbon price, which is currently around €80 per tonne of CO2. If an exporting country has its own carbon tax, the EU reduces the CBAM charge accordingly. However, since India lacks a nationwide carbon pricing system, Indian exporters are liable for the full amount unless special exemptions are negotiated later.

While EU importers are the ones who officially register, calculate emissions, and purchase CBAM certificates, the cost is inevitably passed down the supply chain. European buyers will demand lower prices from Indian suppliers to cover this new expense, directly reducing Indian earnings and bargaining power.

The Critical Role of Data and Production Methods

CBAM is not about voluntary sustainability pledges; it is a rigorous, factory-level accounting system. It counts only Scope 1 (direct fuel use) and Scope 2 (electricity use) emissions for the specific plant manufacturing the exported goods. If Indian exporters fail to provide verified data, EU importers will use default CBAM values, which are set 30–80 per cent above actual emissions, sometimes nearly doubling the cost. Buyers will then demand even steeper price cuts or seek alternative suppliers.

From 2026, emissions data must be verified by auditors approved under ISO 14065 or EU regulations, a qualification not all Indian auditors currently hold, making early preparation vital. Furthermore, CBAM will fundamentally alter export contracts, with European clients likely inserting clauses for cost-sharing, verified data provision, and price renegotiation linked to EU carbon price fluctuations.

The policy also incentivises cleaner production. Coal-intensive steel production faces the highest CBAM burden, while gas-based or scrap-based electric arc furnace (EAF) steel incurs a much lower cost. This creates a clear financial advantage for greener manufacturing processes.

The Path Forward: Negotiation and Domestic Action

The disparity in carbon pricing poses a challenge for developing economies. The EU's charge of ~€80/tonne is far higher than China's carbon price (about 10% of the EU level) and any future price India might set. Critics argue that applying developed-world carbon costs to countries like India raises production costs, hurts exports, and can slow industrial growth with minimal global emission benefits.

The solution lies on two fronts. Internationally, India must seek a resolution on CBAM within the ongoing Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations with the EU. Domestically, it is imperative to strengthen carbon accounting frameworks and support investments in cleaner production technologies.

CBAM represents a structural shift in global trade where carbon efficiency is becoming a core component of competitiveness. For Indian exporters, adapting swiftly through accurate carbon measurement, verified reporting, and strategic shifts in production and pricing is no longer optional—it is essential for survival in the valuable European market.