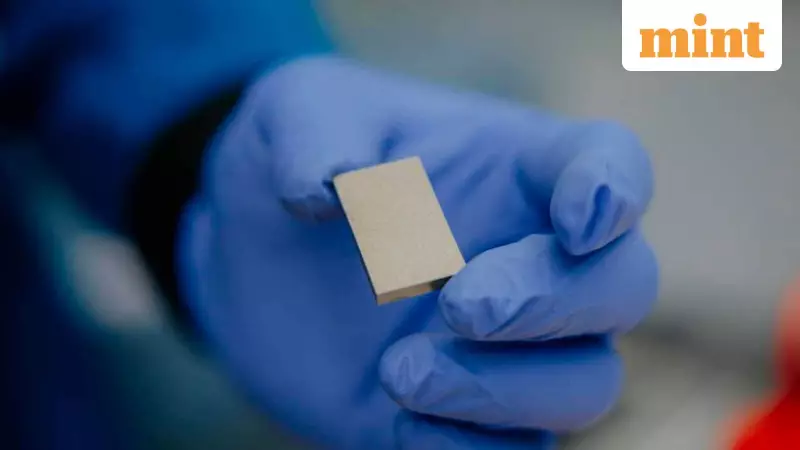

India's first plant producing neodymium–praseodymium (Nd-Pr) metals, essential for high-performance permanent magnets, began operations earlier this year. The facility, commissioned by Pune-based Ashvini Rare Earth, was hailed as a breakthrough. Yet, a critical puzzle remains: why do leading Indian electric vehicle (EV) makers like Ather and Bajaj Auto continue to source their magnets from China?

The Structural Gap Between Metals and Magnets

The answer lies in a deep-seated structural gap in the supply chain. While India can now produce the raw rare-earth metals, it lacks commercial-scale capability in manufacturing the sintered NdFeB magnets required for automotive-grade applications like EV motors and wind turbines. These are far more advanced than the bonded magnets historically made in India for smaller devices.

Switching magnet suppliers is not a simple procurement decision. It involves extensive product redesign, rigorous safety testing, re-homologation, and carries significant warranty risks. For companies like Ather, Bajaj, and TVS, the operational risk of using unproven, domestically produced magnets at scale remains too high, making Chinese imports the only reliable option.

Geopolitical Weaponization of Supply Chains

This dependence exposes a strategic vulnerability, as supply chains have become tools of statecraft. China has demonstrated its willingness to weaponize control over critical inputs. It maintains an export licensing regime for materials like gallium and germanium (vital for semiconductors) and has imposed controls on graphite used in EV battery anodes.

The recent tightening of Chinese export rules on heavy rare-earth magnets sent shockwaves through Indian industry, offering a stark preview of potential disruptions. This situation is a direct consequence of years of underinvestment in building domestic capacity for strategic materials, with a preference for cheaper imports over long-term resilience.

Charting a Strategic Path Forward

To reduce this critical dependence, experts argue India needs a focused and multi-pronged strategy. Smart fiscal support is essential to address the high capital costs for setting up refining and magnet-making cells, the long learning curves to achieve automotive-grade quality, and the demand risk for new factories.

Policy tools could include:

- Capex subsidies and long-term, low-cost credit for domestic suppliers.

- Incentives linked to volume, quality, and reliability, not just installed capacity.

- Demand aggregation by pooling multi-year purchase contracts across automobiles, electronics, and public sector units to assure scale for suppliers.

- Exploring first-loss capital coverage or sovereign guarantees to back private investment.

This approach mirrors components of industrial policy seen in the US (Chips Act), the EU (Critical Raw Materials Act), Japan, and South Korea. India's own Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes echo this philosophy, but success hinges on capturing the full value chain. The proposed Rare Earth Permanent Magnet mission could be the catalyst to move from metal production to full-scale magnet manufacturing.

Geopolitically, the path is not about full decoupling from China, which remains a major trade partner, but about achieving strategic symbiosis. India must diversify sourcing—building domestic capacity where possible, forging alliances for alternative supply, and trading freely with China where dependence is low. The goal is to de-risk aggressively at chokepoints while supporting a rules-based global trade order.

The magnet story underscores that the reliance on China is not about corporate reluctance or a lack of nationalism. It reveals the tangible cost of delayed upstream investment in strategic sectors. As geopolitics now influences the bill of materials, India must treat critical inputs like rare-earth magnets as strategic infrastructure, deploying targeted fiscal policy, regulatory clarity, and global partnerships to secure its industrial and green energy future.