In an unprecedented literary achievement, Hungary has claimed both the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Booker Prize within a single season, establishing the Central European nation as 2025's undisputed capital of world literature. The remarkable dual victory features two authors of Hungarian heritage whose writing styles couldn't be more different yet together represent the spectrum of contemporary literary excellence.

Two Crowns, One Heritage

The autumn of 2025 has witnessed what many are calling Hungary's greatest literary moment in modern history. Within just over a month, both the Nobel Prize in Literature and the prestigious Booker Prize have been awarded to writers connected by Hungarian roots but separated by their artistic visions.

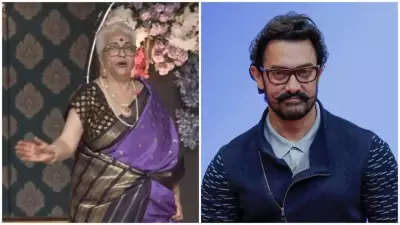

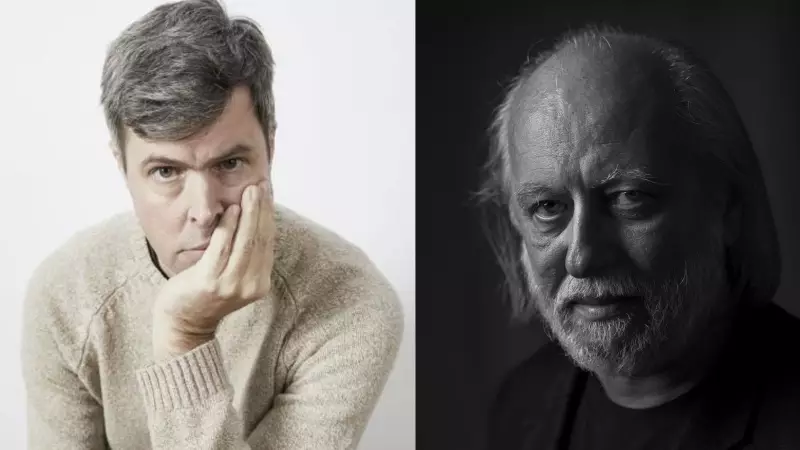

László Krasznahorkai, the reclusive Hungarian master often described as a prophet of apocalyptic terror, received the Nobel Prize for his visionary body of work. Meanwhile, David Szalay, the Hungarian-British novelist known for his precise dissection of modern rootlessness, was honored with the Booker Prize for his sixth novel, Flesh, during a glittering ceremony in London.

Krasznahorkai's Labyrinthine Vision

The Swedish Academy recognized Krasznahorkai for his compelling and visionary oeuvre, celebrating writing that discovers artistic power precisely where conventional reality ends. His novels, including the celebrated Satantango and The Melancholy of Resistance, are not so much traditional narratives as intricate linguistic labyrinths from which readers might never fully escape.

Krasznahorkai's signature style features famously long, winding sentences that critics have compared to rivers overflowing their banks, carrying readers through torrents of philosophical despair and grotesque beauty. He stands as the literary heir to Kafka and Bernhard, a writer who has openly stated his mission involves examining reality to the point of madness.

His collaboration with filmmaker Béla Tarr on the seven-hour black-and-white adaptation of Satantango represents less a conventional film translation and more a shared hypnotic incantation that captures the essence of his literary world.

Szalay's Anatomy of Modern Dislocation

If Krasznahorkai represents the visionary gazing into the abyss, David Szalay serves as the precise anatomist dissecting what emerges from that void. Born in Canada, raised in London, and currently residing in Vienna, Szalay carries his Hungarian heritage as a central tension throughout his work.

During the Booker ceremony, Szalay explained his perspective in a video presentation: Even though my father's Hungarian, I never feel entirely at home in Hungary. I suppose I'm always a bit of an outsider there, and living away from the UK and London for so many years, I also had a similar feeling about London. So I really wanted to write a book that stretched between Hungary and London and involved a character who was not quite at home in either place.

This state of perpetual unbelonging fuels his Booker-winning novel Flesh, which judges praised for its spare prose—a stark contrast to Krasznahorkai's dense textual landscapes. The novel spans from Hungarian housing estates to London's elite mansions, tracing the unraveling of an emotionally detached man and exploring Szalay's recurring theme of the fragile modern male psyche adrift in globalized society.

Literary Significance and Global Impact

This remarkable convergence of literary honors doesn't signal the triumph of a single Hungarian style but rather showcases the opposite poles of contemporary writing. Krasznahorkai's work feels deeply embedded in Hungarian soil and history, its prose rhythms echoing ancient folk tales, while Szalay's writing is fluid, transnational, and immediately contemporary.

Together, these authors bookend the modern human condition: Krasznahorkai provides the grand, terrifying prophecy of systemic collapse, while Szalay offers intimate case studies of individuals navigating the resulting ruins. For readers, this autumn presents a unique opportunity to journey from the metaphysical plains of Krasznahorkai's Hungary to the disorienting corridors of Szalay's Europe—a complete pilgrimage through contemporary anxieties.

The dual recognition represents more than individual achievement—it signals a shift in literature's center of gravity toward voices that understand the end of the world manifests not as a single event but as countless personal, quiet apocalypses. In honoring both these Hungarian-connected writers, the literary world acknowledges that within these endings, we might discover our capacity to endure.