Renowned Bengali filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak fundamentally transformed how sound functions in cinema through his innovative audio techniques that continue to influence filmmakers today. A new examination of his work reveals how he composed soundtracks that actively shaped audience perception rather than simply accompanying visuals.

The Symphony of Man and Machine in Ajantrik

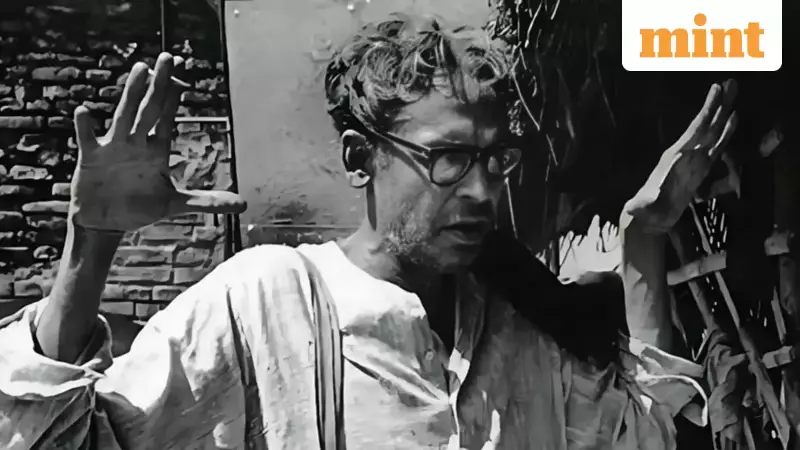

Ghatak's 1958 feature Ajantrik demonstrates his pioneering approach to sound design. The film explores the relationship between taxi driver Bimal, played by Kali Banerjee, and his dilapidated 1920 Chevrolet named Jagaddal. Ghatak used artificial-sounding noises on the soundtrack that evoked science fiction, expressing the protagonist's fascination with treating his vehicle as both a living creature and an extension of his personality.

The various sounds characterizing the automobile through different stages of health became crucial elements in establishing the film's tragicomic tone. When Jagaddal finally breaks down irreparably, the sound of Bimal weeping becomes as significant as the musical score. In the final scene, the harsh sound of the wreck being towed away creates poignant contrast with the detached car horn still wheezing when squeezed by an infant, allowing the hero a sense of triumph.

Reinventing Cinema Through Layered Soundscapes

Ghatak essentially created his films twice - first during shooting and again when composing their soundtracks. According to his son Ritban Ghatak, none of his father's films employed direct sound recording. All were technically required to be post-dubbed, which emphasized how deliberately Ghatak composed his soundscapes.

His highly unorthodox methods of sound composition essentially rethought the dramaturgy of visuals, affecting how audiences perceive images by directing attention toward certain details and away from others. This approach was facilitated by Ghatak's technique of composing both visual mise en scène and aural mise en scène in discrete layers.

Ghatak frequently employed deep focus cinematography, creating counterpoint between background and foreground details reminiscent of Orson Welles' early films. Similarly, his sound layered music, dialogue, and sound effects that ranged from naturalistic, like food cooking on a grill, to expressionistic, such as the recurring sound of a cracked whip.

A Radical Approach to Film History

Film scholars identify two basic approaches to filmmaking: working within existing traditions or proceeding radically as if no one had made films before. Ghatak belongs to the rare second category alongside figures like Danish filmmaker Carl Dreyer and American experimental director Stan Brakhage.

His methods of composing soundtracks and interrelating sounds with images demonstrate his unique contribution to cinema. Ghatak reinvented cinema for his own purposes both conceptually, through his overall working methods, and practically, by rethinking the nature of shots he had already filmed.

He achieved this by starting and stopping sounds at unexpected moments, creating unorthodox ruptures in mood and tone. These radical breaks in his soundtracks represent pure moments of creation that reinvent cinema by reinventing spectators, keeping audiences more alert than conventional soundtracks would.

While Ghatak's lectures and essays, collected in Rows and Rows of Fences: Ritwik Ghatak on Cinema, don't explicitly acknowledge these ruptures, their effect remains profoundly innovative. Like many artists, what Ghatak accomplished through his filmmaking practice may ultimately speak more powerfully than his theoretical statements about his methods.

These insights come from Unmechanical: Ritwik Ghatak in 50 Fragments, edited by Shamya Dasgupta and published by Westland, offering fresh perspectives on the legendary director's enduring legacy in Indian and world cinema.