5,000-Year-Old Ice Cave Bacterium Shows Resistance to Modern Antibiotics

In a groundbreaking discovery, a team of Romanian researchers has identified a bacterium preserved for approximately 5,000 years within an underground ice deposit that already exhibits resistance to multiple modern antibiotics. This ancient organism, recovered from the Scărișoara Ice Cave in north-west Romania, survived frozen conditions for millennia and demonstrated resilience against drugs commonly used today to treat infections of the lungs, skin, blood, and urinary tract.

Study Details and Methodology

The study, recently published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology, raises alarms about both the potential hazards and scientific opportunities presented by organisms exposed as warming temperatures penetrate long-sealed environments. These include areas covered by permanent ice, such as glaciers, ice sheets, and ice caps, which collectively cover about 10% of the Earth's land surface.

To retrieve this strain, the research team drilled a 25-metre ice core from the cave's "Great Hall," representing around 13,000 years of accumulated ice. To prevent contamination, fragments were placed in sterile bags and transported frozen to the laboratory, where multiple bacterial strains were isolated and sequenced.

Key Findings on the Bacterium

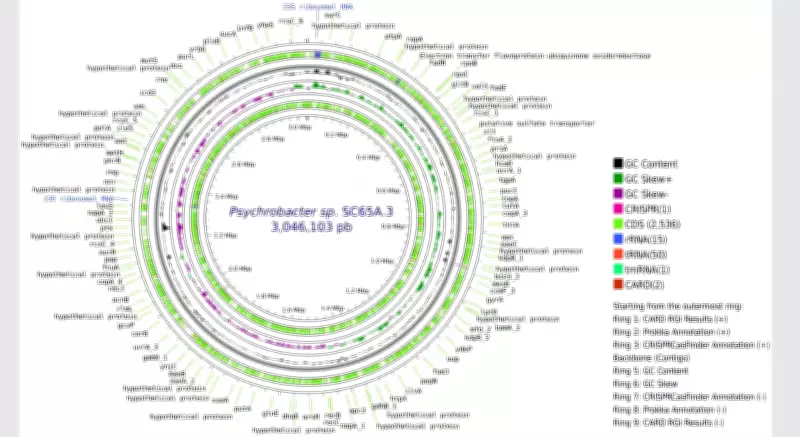

The most notable organism identified was Psychrobacter SC65A.3, a cold-adapted bacterium from a genus previously linked to infections in humans and animals. Dr. Purcarea, a lead researcher, stated, "The Psychrobacter SC65A.3 bacterial strain isolated from Scărișoara Ice Cave, despite its ancient origin, shows resistance to multiple modern antibiotics and carries over 100 resistance-related genes."

Genetic analysis confirmed the strain possesses more than 100 resistance-related genes. When tested against 28 antibiotics from 10 classes routinely used in human medicine, the bacterium proved resistant to 10 of them. These included drugs like trimethoprim, clindamycin, and metronidazole, which are employed to treat infections of the lungs, skin, blood, reproductive system, and urinary tract.

Dr. Purcarea emphasized, "The 10 antibiotics we found resistance to are widely used in oral and injectable therapies for treating a range of serious bacterial infections in clinical practice."

Implications for Antibiotic Resistance

The findings shed light on the natural evolution of antibiotic resistance. "Studying microbes such as Psychrobacter SC65A.3, retrieved from millennia-old cave ice deposits, reveals how antibiotic resistance evolved naturally in the environment, long before modern antibiotics were ever used," the researchers noted.

While ancient microbes do not automatically signal an impending pandemic, they represent genetic reservoirs. If thawing environments release them, their resistance traits could transfer to contemporary bacteria. Dr. Purcarea explained, "If melting ice releases these microbes, these genes could spread to modern bacteria, adding to the global challenge of antibiotic resistance."

Antibiotic resistance is often associated with overuse in medicine and agriculture, but this discovery indicates some mechanisms existed in nature long before human intervention. Scientists warn that warming climates increase exposure risks to long-frozen organisms, citing a 2016 Siberian heatwave that thawed permafrost and triggered an anthrax outbreak from an infected reindeer carcass, killing a child and infecting several people.

Potential Benefits and Future Research

Beyond risks, the bacterium's genome offers unexplored biological potential. Researchers identified 11 genes capable of killing or inhibiting bacteria, fungi, and viruses, along with nearly 600 genes with unknown functions. Cold-adapted strains like this may serve as reservoirs for antimicrobial compounds and enzymes.

Dr. Purcarea highlighted, "On the other hand, they produce unique enzymes and antimicrobial compounds that could inspire new antibiotics, industrial enzymes, and other biotechnological innovations." She added that while these ancient bacteria are scientifically valuable, careful handling and safety measures in the lab are essential to prevent uncontrolled spread.

This discovery underscores the dual nature of thawing ice environments: as sources of both potential health threats and promising medical resources, urging further study and cautious exploration in the face of climate change.