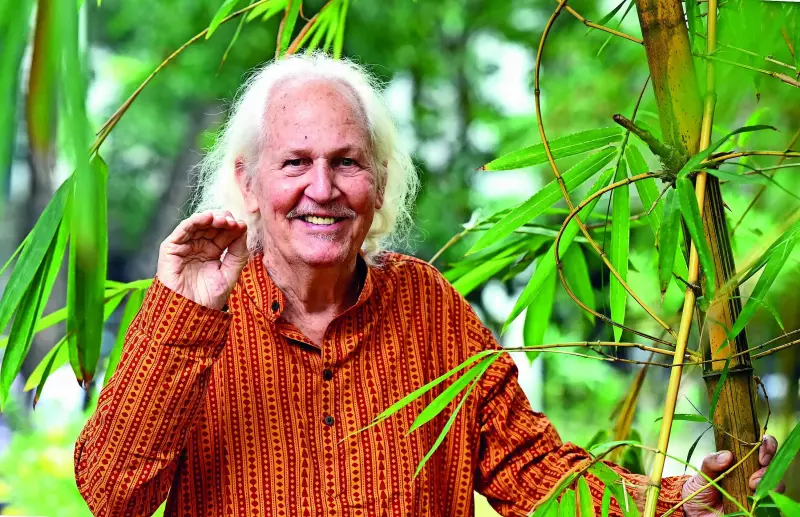

In 1957, a 13-year-old boy on a family trip to Kerala experienced a moment that would define his life's path. As a boat drifted on the Periyar waters, a tiger emerged silently from the forest edge, moving like a shadow. For Romulus Whitaker, this electrifying encounter with wild India, long before it was confined to sanctuaries, planted the seed for his future as one of the nation's most influential conservationists.

The Making of a Conservationist: From New York to Kerala

Whitaker's first journey to India was part of a celebration for his sister's high school graduation. The family stayed at Kochi's premier Malabar Hotel and took popular boat rides where sightings of gaurs, deer, and even tigers were common. "I never saw a king cobra on that trip, but the habit of looking closely had already taken root," Whitaker recalls. His fascination with reptiles, however, began far away in northern New York State. After seeing neighborhood boys kill a snake out of fear, his mother nurtured his curiosity by buying him a book on snakes. When he later brought a live snake home, she admired its beauty, allowing him to keep it in an old, cracked aquarium.

This early engagement deepened when his family moved to India in the 1950s. His partner and co-author, Janaki Lenin, notes that Whitaker's schooling was unconventional, filled with forest camping, lake fishing, and even discovering a python under his bed. Formal education never suited him. After a brief stint in college, he found his true calling at the Miami Serpentarium under legendary snake handler Bill Haast. "Bill Haast was my guru. He taught me respect for snakes, not just technique," says Whitaker, who learned to handle venomous snakes and extract venom for medical use.

Transforming Fear into Science: The Madras Snake Park & Beyond

Returning to India with a clear vision, Whitaker sought to replace blind fear with scientific understanding. This idea materialized in 1969 with the founding of the Madras Snake Park. It was an educational experiment, not entertainment, allowing the public to see snakes up close, learn species identification, and realize most snakes are not intent on harm. Today, India has thousands of snake rescuers, a development Whitaker views with cautious optimism. He particularly praises Kerala for institutionalizing rescue work through registered rescuers, ID cards, and an online database—a model now adopted by Karnataka and being replicated in Tamil Nadu.

Despite progress, snakebite remains a severe public health crisis. For decades, official figures cited around 1,400 annual deaths, but the "Million Deaths Study" revealed a grim reality: over 50,000 deaths yearly from nearly one million incidents. Whitaker emphasizes prevention—using torches at night, wearing footwear, and caution near pump houses. The bigger challenge is treating snakebite as a medical emergency, not a mystical event.

Sustainable Solutions: The Irula Model & Managing Conflict

One of Whitaker's most impactful collaborations is with the Irula tribal community in Tamil Nadu. After the snake skin trade ban devastated their livelihood, Whitaker helped create a sustainable alternative. Irula catchers now capture snakes, extract venom under controlled conditions, and release them. This venom supplies pharmaceutical companies to produce antivenom. "They are saving lakhs of human lives," Whitaker states. Today, about 350 Irula families supply venom meeting India's entire antivenom need, representing a rare model of sustainable wildlife use.

On broader human-animal conflict, Whitaker notes that India's growing tiger, leopard, and crocodile populations increasingly live outside protected forests. Leopards have adapted to agricultural landscapes, raising cubs in sugarcane fields. "Leopards don't need forests the way we think they do," he explains. He criticizes reactive measures like relocation, which often worsen conflict. From personal experience after losing a dog to a leopard near his Chennai farm, he learned that simple precautions—keeping pets indoors at night—are more effective.

He is also critical of policies like in Kerala, where farmers can legally kill crop-raiding wild boars but must bury the carcasses, wasting a potential protein source. Science-based preventive infrastructure, he argues, works better than reactionary measures.

A Legacy of Advocacy and a Call to Action

Whitaker credits former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi as India's most conservation-minded leader, instrumental in the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972. "These were the times when you could actually speak to a prime minister and the next day you might see some action," he recalls, contrasting it with today. After receiving the Padma Shri, he briefly met Prime Minister Narendra Modi and later sent a draft message hoping for a mention of snakebite prevention in 'Mann Ki Baat'. "If the PM spoke for even one minute about snakebite as a medical emergency... thousands of lives could be saved," he asserts.

Now in his eighties, Whitaker continues focusing on snakebite mitigation through films and awareness. From the boy who defended a snake to the man who persuaded a nation to rethink its fears, his journey underscores a lifelong commitment to choosing scientific knowledge over fear. His advice to aspiring herpetologists is simple: "Observe, respect, and don't try to be a hero. Conservation is about patience and understanding, not spectacle."