From Henry VIII to Sarah Mullally: The Church of England's 500-Year Journey

In the classic British satire Yes Minister, when Jim Hacker discovers that Italian terrorists possess British-made weapons, Sir Humphrey Appleby dismissively notes it's not their department's concern. He suggests it's a matter for the Defence Ministry or Foreign Office, prompting Hacker to retort, "I am talking about good and evil." Sir Humphrey wryly responds that this makes it a "Church of England" problem. This humorous exchange highlights the enduring complexity of moral authority within an institution born from royal ambition.

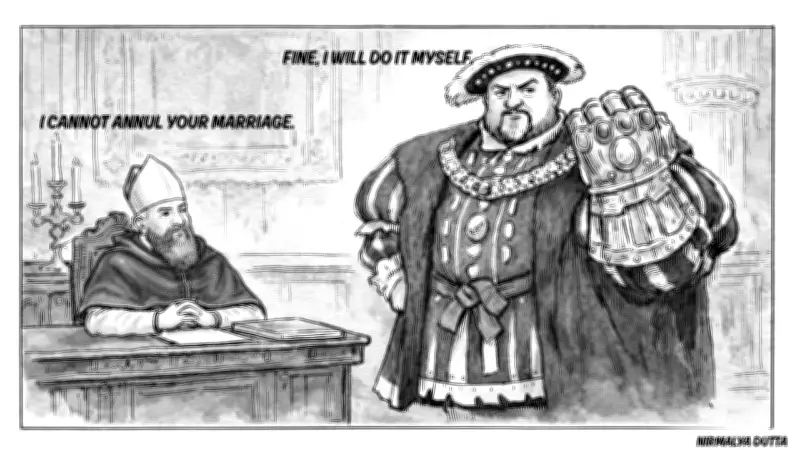

The Origins: Henry VIII and the English Reformation

The Church of England's story begins with King Henry VIII, who sought to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon after failing to produce a male heir. When Pope Clement VII refused—partly due to pressure from Catherine's nephew, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V—Henry took drastic action. In 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, effectively nationalising Roman Catholicism in England and establishing the monarch as the head of the church. This marked the birth of the Church of England, separating it from papal authority.

Liturgical Independence: The Book of Common Prayer and King James Bible

Under Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the Church developed its unique identity. In 1549, Cranmer introduced the Book of Common Prayer, translating Latin Catholic rites into English and standardising worship across the kingdom. This work, along with the King James Version of the Bible published in 1611, provided England with a liturgical framework that blended Protestant theology with Catholic ceremony. These texts became cultural touchstones, with phrases like "ashes to ashes, dust to dust" and "till death us do part" entering common usage.

Evolution Through Centuries: Puritanism, Revival, and Modernisation

The Church's history has been marked by internal conflicts and adaptations:

- During the English Civil War, Puritans briefly gained control under Oliver Cromwell, suppressing episcopal traditions before the monarchy's restoration.

- In the 18th century, preachers like John Wesley emphasised personal faith, leading to the rise of Methodism.

- The 19th-century Oxford Movement advocated for reclaiming Catholic-style rituals, highlighting ongoing tensions between tradition and reform.

Throughout, the Church remained intertwined with the British state, with bishops in Parliament and monarchs as its supreme governors.

The 20th and 21st Centuries: Secularism and Progressive Shifts

The modern era brought significant changes:

- Declining attendance in an increasingly secular Britain has challenged the Church's relevance.

- Gender inclusivity advanced with women ordained as priests in 1994 and as bishops in 2015.

- LGBT+ issues remain contentious, with same-sex marriages not solemnised but blessings permitted.

- Abuse scandals have eroded public trust, exposing institutional failures.

Sarah Mullally: A Historic Appointment

In 2026, Dame Sarah Mullally became the first female Archbishop of Canterbury in nearly 1,400 years. A former nurse and administrator, her background suggests a pragmatic approach to leadership. Her appointment, formally made by King Charles III on advice from Prime Minister Keir Starmer—an atheist—epitomises the Church's complex relationship with the state.

Reactions to her appointment have been mixed:

- Many in Britain celebrate it as a progressive milestone.

- Conservative Anglican leaders globally have criticised it.

- The Vatican issued a neutral statement, reflecting its own stance against female ordination.

Challenges Ahead: Decline, Division, and Credibility

Mullally inherits a church facing three core challenges:

- Decline: Falling attendance threatens its spiritual vitality.

- Division: Internal conflicts over gender, sexuality, and doctrine persist among evangelical conservatives, Anglo-Catholic traditionalists, and liberal reformers.

- Credibility: Safeguarding scandals have damaged moral authority.

As one Canterbury tour guide noted about previous archbishops, "Some of them have been very good, some of them have been pretty bad. Some of them have been very contentious, and some of them ended up murdered. I hope it doesn't happen to this one." This blunt assessment captures the high stakes of her role.

Conclusion: Irony and Legacy

The Church of England's journey from Henry VIII's divorce to Sarah Mullally's leadership is rich with irony. An institution created by a king seeking marital freedom is now led by a woman steering one of the world's most influential Christian denominations. As Sir Humphrey might quip, this development likely involved inter-departmental committees, while Hacker would ponder its electoral implications. Ultimately, the Church continues to navigate its hybrid identity—Catholic in structure, Protestant in doctrine—amidst the pressures of modernity.