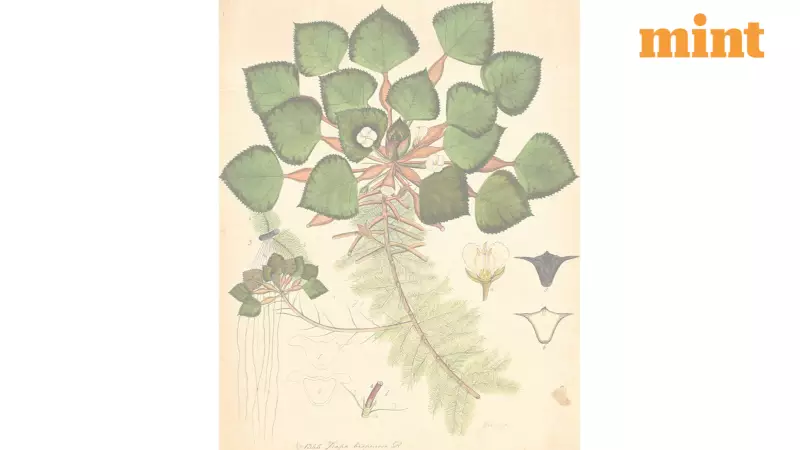

Rediscovering India's Botanical Heritage Through Colonial-Era Paintings

"These are palimpsests that combine art and science," explains Henry J. Noltie, the distinguished taxonomist, curator, and botanical historian, as he describes the remarkable paintings we are examining. Created during the 18th and 19th centuries by talented Indian artists, these exquisite works were commissioned primarily by East India Company officers and later British authorities to systematically document the subcontinent's rich biodiversity. The taxonomic precision in these paintings is so pronounced that many remain only partially colored, with just enough detail for botanists to reconstruct complete specimens from the delicate outlines.

A Morning in Delhi: Discussing Flora Indica and Its Mission

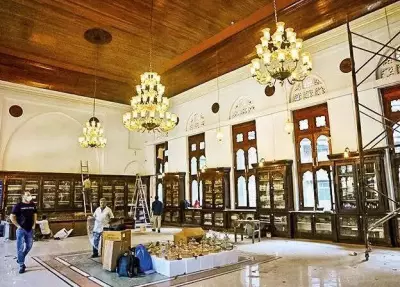

On a particularly overcast morning in Delhi, at his publisher's office, Noltie discusses his latest publication, Flora Indica. This beautifully produced catalogue accompanies an exhibition at London's Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (running until 12 April). The book's subtitle, Recovering Lost Stories From Kew's Indian Drawings, clearly articulates the project's dual objectives: to celebrate India's botanical heritage while making reparations to the artists whose names have been largely forgotten despite their significant contributions.

The Daunting Task of Selection and Organization

Noltie, who dedicated his long career to the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, undertook the formidable challenge of reviewing over 7,500 botanical paintings from Kew's collection, selecting only a curated few for exhibition. Collaborating with historian and independent researcher Sita Reddy, he organized both the show and book around three comprehensive themes: "The life of the paintings, the lives of the artists who made these, and the afterlife of the works and their makers." The current selection emphasizes paintings from North India, particularly from herbariums in Saharanpur and Calcutta (present-day Kolkata), while southern works reveal distinct styles and narratives. This endeavor uncovers not merely a historical fragment but a captivating, complex jigsaw puzzle—partially coherent yet far from complete.

Reviving the "Company School" Artists

In recent years, scholarly efforts to reclaim the identities of 18th and 19th century Indian artists—previously grouped under the generic "Company School" label—have gained significant momentum. The 2019 exhibition Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting For The East India Company, curated by historian William Dalrymple at London's Wallace Collection, showcased diverse works by artists like Mazhar Ali Khan, Yellapah of Vellore, Shaikh Zain ud-Din, Bhawani Das, and Manu Lall. Beyond highlighting India's flora, fauna, and people, this exhibition illuminated the varied artistic approaches these painters employed.

Humanizing the Artists Through Archival Discoveries

Noltie's work advances this mission by humanizing artists in unprecedented ways. During his archival research, he uncovered a poignant letter from senior artist Vishnuprasad to his former supervisor, Nathaniel Wallich, who had recently resumed his role as Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Garden after nearly five years in Europe. Beyond requesting reinstatement to Calcutta from Saharanpur, Vishnuprasad's letter, with its imperfect English, reveals a personality long obscured by the anonymous "Company School" categorization.

Patronage and the Erasure of Artistic Identity

The responsibility for this historical erasure largely rests with the original patrons. Colonial officials rarely documented artists' names, typically identifying works by collection—such as the Fraser Album or commissions by Scottish botanist William Roxburgh. Even esteemed scholars like the late B.N. Goswamy initially deemed recovering these names unworthy. Recently, however, researchers have begun scrutinizing accompanying paper trails, uncovering both provenance details and artist identities.

Attribution Challenges and Discoveries

Noltie's fortunate discovery of stylistically unique paintings led him to their creators, aided by Adam Freer's meticulous attribution practices. Conversely, some labels incorrectly credit British artists like Mary Govan—a trained artist who did embellish certain works—though such anomalies often stem from later family additions. Despite generally disrespectful attitudes toward painters, British patrons compensated them relatively well compared to gardeners and other staff. Compassionate patrons like Hugh Falconer even advocated for pensions for deceased artists' widows.

Talent Triumphs: The Case of Lutchman Singh

Artistic talent frequently overcame personal flaws, as exemplified by Lutchman Singh. Despite youthful indiscretions, his exceptional skills earned forgiveness from his masters, with Noltie describing him as a "loveable rogue." Singh ultimately enjoyed a prosperous, decades-long career, likely earning enough to sustain himself into old age when life expectancy was considerably lower.

Colonial Context and Environmental Insights

Like most colonial endeavors, the botanical mission reflected desires to control, tame, and classify. Historian Eugenia W. Herbert's 2013 study Flora's Empire: British Gardens in India demonstrated how British "garden imperialism" enriched the Raj through opium and tea cultivation. "The officials who commissioned these paintings were not ecologists," Noltie clarifies, "though they were deeply interested in natural history." Nevertheless, paintings like one depicting a fern reveal how climatic and environmental changes have affected species over centuries—where trees once towered meters high (shown alongside a Lepcha person), they no longer do.

Future Revelations Through Digitization

As these invaluable paintings undergo digitization and become accessible to broader scholarly communities, further revelations about India's botanical and artistic heritage will undoubtedly emerge, continuing to enrich our understanding of this intricate historical tapestry.