How the Supreme Court Settled the Constitutional Question of Chief Ministers Without House Seats

The recent controversy in Maharashtra, where a lawyer questioned the legality of Sunetra Pawar taking oath as Deputy Chief Minister without being an elected Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) or Legislative Council (MLC), has brought renewed attention to a long-standing constitutional provision. This discomfort with unelected executives has deep roots in Indian political history, particularly during the turbulent late 1960s.

The Constitutional Foundation: Article 164(4)

Article 164(4) of the Indian Constitution provides the legal basis for such appointments. It explicitly allows a person to be appointed as a minister, including the position of Chief Minister, for up to six consecutive months without being a member of either house of the state legislature. The crucial condition is that the individual must secure membership within this six-month period to continue in office.

This constitutional provision remained largely untested until the political instability of the late 1960s created circumstances where it became practically necessary. The weakening of the Congress party and the emergence of fractured mandates led to innovative political maneuvers that ultimately required judicial clarification.

The Bihar Precedent: A Five-Day Chief Ministership

The first significant test occurred in Bihar following the 1967 elections, which produced the state's first non-Congress government under the Samyukta Vidhayak Dal (SVD) coalition. After political disagreements caused the SVD government to collapse, Bindeshwari Prasad Mandal emerged as the consensus candidate for Chief Minister with Congress support.

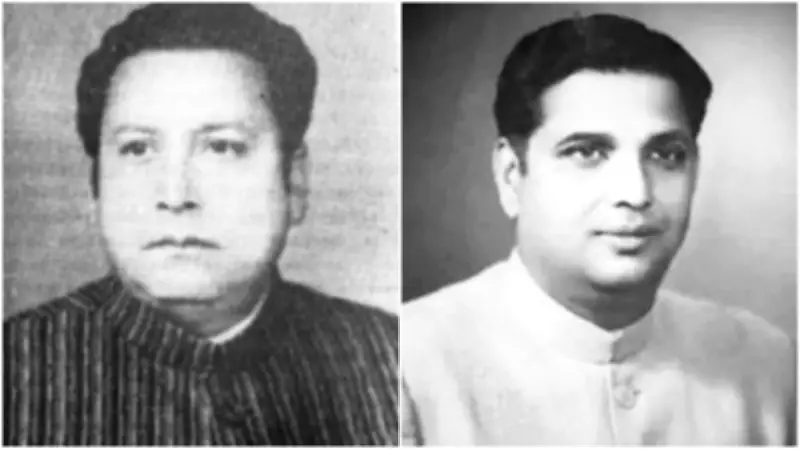

However, Mandal faced a constitutional hurdle: he was not a member of either the Bihar Legislative Assembly or Legislative Council. The political solution was both ingenious and temporary. On January 28, 1968, Satish Prasad Singh, a 37-year-old MLA from the SSP who had been elected from the Parbatta Assembly seat, was sworn in as Chief Minister. Singh thus became Bihar's first OBC Chief Minister, though his tenure was deliberately brief.

Just two days later, Singh facilitated Mandal's nomination to the Legislative Council and promptly resigned. His chief ministership lasted exactly five days, demonstrating how Article 164(4) could be utilized in practice, though the provision's constitutional validity remained formally untested.

The Uttar Pradesh Test and Supreme Court Verdict

The constitutional question moved to the forefront in Uttar Pradesh during 1969-70, another period of political instability. After Charan Singh's government collapsed and President's Rule was lifted, a new coalition government took shape. On October 18, 1970, Tribhuvan Narain Singh, a Rajya Sabha member from Congress (O), was sworn in as Uttar Pradesh's sixth Chief Minister despite not being an MLA or MLC.

Opposition leader Narain Dutt Tiwari immediately challenged Singh's legitimacy, while Lucknow resident Har Sharan Verma filed a petition in the Allahabad High Court arguing the appointment violated constitutional provisions. When the High Court dismissed the plea, Verma appealed to the Supreme Court.

On March 16, 1971, the Supreme Court delivered its landmark verdict, firmly establishing three key principles:

- A person can be appointed Chief Minister without being an MLA or MLC

- Article 164(4) applies specifically to Chief Ministers, not just ministers

- Such appointments remain valid for up to six months

The judgment represented a constitutional victory for Singh, though it couldn't secure his political survival. To comply with Article 164(4), he contested a by-election from the Maniram Assembly seat (now Gorakhour Urban) but lost, making his resignation inevitable. His government fell on March 30, 1971, during discussion of the Motion of Thanks on the Governor's address.

Lasting Impact on Indian Politics

The Supreme Court's 1971 verdict settled the constitutional position definitively, creating a precedent that has enabled several Chief Ministers to take oath without immediate legislative membership. The ruling balanced constitutional flexibility with democratic accountability by maintaining the six-month limit for securing legislative membership.

This legal framework continues to influence Indian politics, providing constitutional accommodation for political realities while ensuring that unelected executives cannot indefinitely govern without securing democratic mandate through legislative membership. The recent Maharashtra controversy demonstrates how this decades-old constitutional provision remains relevant in contemporary political discourse.