Gandhi's Collective Leadership: A Rebuttal to Partition-Era Misconceptions

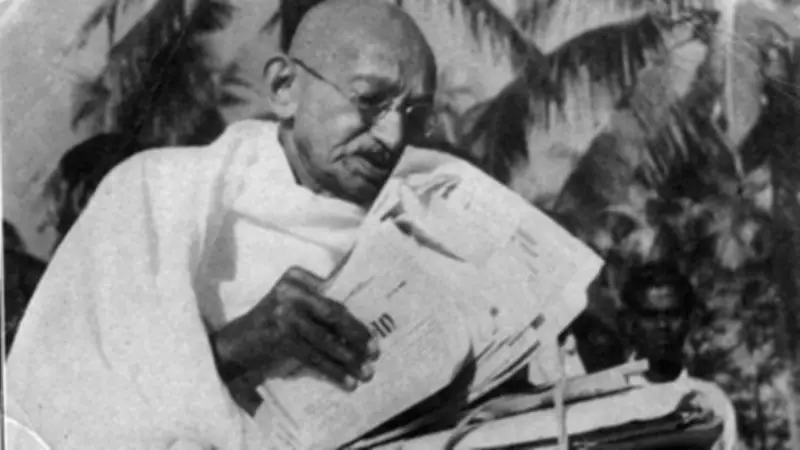

In a recent opinion piece, Ram Madhav revisits the tumultuous era of India's Partition, making assertions that demand a nuanced historical examination. Contrary to popular simplifications, Mahatma Gandhi's approach was that of a practical idealist, whose life was a continuous experiment with truth. This perspective is often overshadowed by partisan narratives.

The Dynamics of Congress Leadership

Madhav argues that Gandhi persistently tried to prevent Partition until the end, while Jawaharlal Nehru allegedly sought political power by any means. However, this overlooks the intricate power-sharing within the Congress. The organization was not a monolithic entity but a collective effort. Political scientist Granville Austin aptly described it as "the oligarchy of four," comprising Rajendra Prasad, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Nehru, and Maulana Azad.

Patel himself acknowledged in November 1948 that Nehru commanded a broader public following, whereas Patel had stronger organizational support. This division of labor was not a weakness but a strategic collaboration, with Nehru focusing on ideological leadership and Patel on administrative groundwork.

Nehru's Role and Gandhi's Trust

Madhav's critique extends to Subhas Chandra Bose, suggesting Bose saw through Nehru's "bluff." Historical records, however, indicate Bose was more critical of Patel than Nehru. As noted by Nirad Chaudhuri, Nehru remained aloof from the rancor between Gandhi and Bose, demonstrating his diplomatic acumen.

Nehru never hid his differences with Gandhi, who was well aware of Nehru's radical leanings. Yet, Gandhi believed this radicalism could be tempered. When Nehru assumed the Congress presidency in 1936, he moderated his stance, recognizing the limited support for the Left and the organizational control held by Patel and Prasad. Gandhi viewed Nehru as a counterbalance to Bose's appeal among urban intellectuals and youth, ultimately seeing him as a successor capable of guiding the nation without disrupting its fragile political equilibrium.

External Pressures and Colonial Machinations

A critical omission in Madhav's analysis is the role of external actors. Viceroy Linlithgow, influenced by Winston Churchill and other imperial defenders, encouraged Muhammad Ali Jinnah's belligerence towards the Congress. The Muslim League's offer of unconditional support to the British during World War II, in exchange for recognition as the sole representative of Indian Muslims, exacerbated tensions.

In response, the Congress, under collective leadership, hardened its position. Nehru's perceived unilateralism was, in part, a reaction to the divisive tactics employed by Linlithgow and Jinnah. Gandhi, ever perceptive, understood the colonial game of divide and rule. On April 1, 1940, he stated, "Muslims have the same right of self-determination that the rest of India has. We are at present a joint family. Any member may claim division."

The Path to Partition and Beyond

Following the failure of the Gandhi-Jinnah talks in 1944, the younger generation, led by Nehru and Patel, took charge. The 1946 elections solidified the Congress and Muslim League as dominant forces. Despite Gandhi's vehement opposition to Partition and his unwavering commitment to composite nationalism, the geopolitical realities led to division.

It is essential to remember Gandhi as a practical idealist. His leadership style fostered a collaborative environment where Patel and Nehru functioned as two sides of the same coin, steering India toward a stable democratic order. In any triangular political situation, as the writer notes, two sides invariably outweigh the third—a principle that shaped the Congress's strategic decisions during this critical period.

This collective leadership, rooted in trust and shared vision, remains a testament to Gandhi's enduring legacy in navigating one of history's most complex transitions.