The Communist Party of India (Maoist), once described by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh as India's gravest internal security threat, faces an existential crisis following the killing of top commander Madvi Hidma in an encounter in Andhra Pradesh. This development represents the latest in a series of operational setbacks that have nearly decimated the leftwing rebel group.

The Decline of a Revolutionary Movement

The CPI (Maoist) formed over 21 years ago on September 21, 2004, through the merger of the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) and the CPI Marxist-Leninist (People's War). At its peak, the organization had presence in almost one-third of India's districts, drawing inspiration from the Naxalbari movement that began in West Bengal during the late 1960s.

The party's founding document from October 2004 clearly distinguished it from other Communist parties by rejecting parliamentary democracy. Instead, it advocated for armed agrarian revolutionary war with the central objective of seizing power through Mao Zedong's theory of protracted people's war - encircling cities from the countryside and eventually capturing them.

Violent Escalation and Government Response

Between 2005 and 2012, India witnessed a sharp escalation in Maoist violence following the formation of CPI (Maoist). In response, the Chhattisgarh government launched the Salwa Judum movement from 2005 to 2009, which utilized tribal civilians to counter Maoist influence.

The situation intensified in 2009 when then Union Home Minister P Chidambaram launched Operation Green Hunt to confront rebels in their forest bases. However, the Maoists delivered a devastating blow on April 10, 2010, ambushing and killing 75 CRPF jawans in Dantewada - their deadliest attack to date, which effectively halted the operation.

Despite this demonstration of strength, the Maoists suffered a significant setback in 2013 when they attacked a Congress motorcade in Chhattisgarh, wiping out almost the entire state leadership of the party, including Vidya Charan Shukla and Mahendra Karma.

Historical Context and Ideological Challenges

The current challenges facing CPI (Maoist) mirror historical patterns. The original Naxalite movement was curbed within 72 days during a strong government crackdown in the early 1970s. Police arrested movement leader Charu Mazumdar in 1972, and he subsequently died in Alipore jail. The movement splintered into four main factions:

- Dakshin Desh, which became MCC in 1975

- People's War Group (PWG)

- CPI M-L (Party Unity)

- CPI (M-L) Liberation

Professor Aditya Nigam has critically examined the class and caste composition of Maoist leadership, noting that the voice of the revolutionary is almost always that of a Brahmin/upper caste while the people actually dying in battles are almost all Adivasis.

Author Dilip Simeon similarly observed that the Maoist movement has been led by middle-class ideologues who claim to represent the people.

Current Crisis and Future Prospects

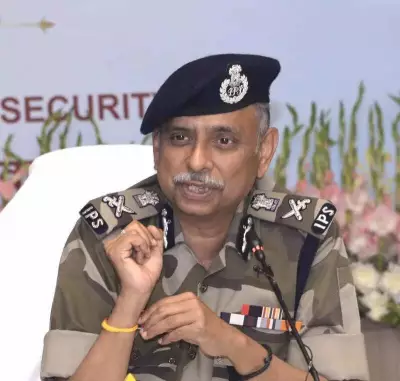

The killing of Madvi Hidma, who masterminded several attacks over two decades, represents another major blow to the already weakened organization. The central and Chhattisgarh governments are racing to eliminate Maoism by March 31, 2026, the deadline set by Union Home Minister Amit Shah.

According to Deepak Kumar Nayak of the Institute of Conflict Management in Delhi, the Maoists lost the ideological battle much before the current military reverses. He noted that after the arrest of Politburo member Kobad Ghandy in 2009, who spent a decade in prison, the movement lost its ideological heft.

What remains today, according to experts, is sectional and local elements with criminal characteristics rather than ideological commitment. With the expansion of the Indian state's presence in remote areas and the destruction of Maoist urban networks, many analysts believe the ideological glue that once held the party together has dissolved.

The material conditions in backward areas that previously helped Maoist groups survive have gradually changed through government initiatives like road-building projects, police station establishments in vulnerable areas, and MNREGA providing tribal communities with better incomes. Professor Shivaji Mukherjee of the University of Toronto notes that these developments contributed to violence levels dipping below the usual annual average of 400 deaths during 2013-15.