Bonded Labor's Enduring Shadow in India: A 50-Year Retrospective

Even after five decades since its formal abolition, the scourge of bonded labor continues to cast a long and dark shadow over India's democratic promises. This persistent issue, rooted in historical exploitation, remains a stark contradiction to the nation's constitutional guarantees and modern aspirations.

Cinematic Reflections and Historical Context

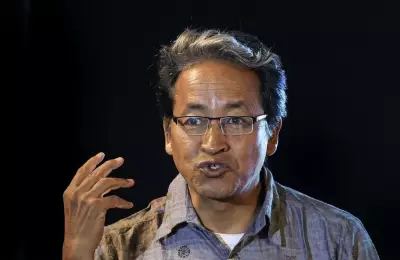

The recent Oscar entry Homebound by filmmaker Neeraj Ghaywan brings personal insight into the struggles of Dalit laborers, echoing themes from Shyam Benegal's 1974 debut Ankur, which highlighted labor exploitation and poverty. These artistic narratives underscore a grim reality that has persisted through the ages.

In 1974, during the Emergency, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi announced the Twenty-Point Programme, with its fourth point boldly declaring the abolition of bonded labor as a barbarous practice. This led to the passage of The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act on January 28, 1976, becoming law on February 9, 1976. The Act aimed to enforce constitutional provisions like Article 23(1), which prohibits forced labor, yet its implementation has faced significant challenges.

Modern Manifestations and Systemic Failures

Bonded labor, defined as debt bondage where laborers are forced to work to repay loans, persists in various sectors. Victims are found in industries supplying bricks, sugar, silk, ginger, and coffee, often through unskilled labor. Even government contractors, via complex subcontracting layers, have been implicated in using bonded construction laborers at official worksites.

Migrant workers, displaced from their homes, are particularly vulnerable to bondage in such settings. In rural areas, traditional systems like bitti chakri in Karnataka continue to demand free labor from the poor, bypassing legal protections. Caste biases and judicial delays further hinder enforcement, as seen in Supreme Court Justice Hemant Gupta's 2022 remarks about misuse of the Act.

Technological and Systemic Shortcomings

Technological interventions like Aadhaar, intended to prevent fraud in government benefits, sometimes exclude eligible workers due to biometric failures, with no systemic accountability for inclusion. Similarly, electoral roll revisions focus on excluding fraud rather than ensuring all eligible citizens are registered.

The new labor codes, effective from 2025, replace inspectors with facilitators, but in practice, this often benefits employers over workers. A core issue remains the non-payment of living wages, which fuels exploitation. Criminal penalties for debt bondage exist, but prevention through payment assurance is increasingly feasible with modern technology.

Pathways to a Future Free of Bonded Labor

Blockchain-based systems could ensure transparent disbursement of government payments down to the last worker in subcontracting chains. By resolving payment issues and strengthening enforcement, India can move toward a future where bonded labor is truly abolished, aligning with its democratic ideals and constitutional promises.