A massive logjam of over 3,200 cases related to illegal construction is currently overwhelming the judicial system of Goa's village panchayats. Governance experts are raising alarms, describing this crisis as a systematic erosion of local self-governance that appears to benefit the powerful construction lobby in the state.

The Staggering Scale of the Backlog

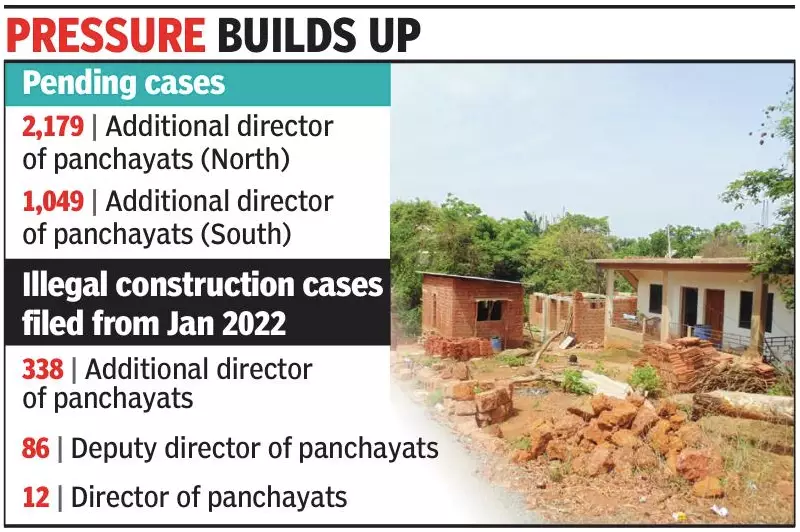

Official data paints a grim picture of the administrative paralysis. A total of 3,228 cases are pending across the state's panchayat directorates. The breakdown reveals that the Additional Director of Panchayats for North Goa is saddled with 2,179 unresolved cases, while the counterpart in South Goa has another 1,049 cases awaiting a decision.

Focusing on more recent violations, the situation remains dire. From January 2022 onwards, 436 new cases have piled up at various levels within the directorate. Of these, 338 are before the courts of additional directors, 86 before deputy directors, and 12 are even pending before the court of the Director of Panchayats himself.

A Flawed System Designed to Fail

Soter D'Souza, a noted expert on panchayati raj who has extensive grassroots experience, explains that the current workflow is fundamentally broken. He traces the root of the problem to a key policy shift. "Up until 2010, building files came to the panchayats first," D'Souza told The Times of India. The change came after the anti-regional plan movement of 2010, which led to the creation of the Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010.

This act made the Town and Country Planning (TCP) Department the nodal agency. "Now all construction files go to the TCP first, without the panchayat's knowledge," D'Souza stated. The TCP conducts inspections and issues No Objection Certificates independently. Only after securing TCP approval does a builder approach the local panchayat for the final construction licence.

This creates an immediate conflict. When a panchayat tries to reject an application based on local infrastructure deficits—like garbage management issues, water shortages, or electricity constraints—the applicant simply appeals to a government-appointed director. "They go in appeal before these directors, who are govt officers, and the cases get kept pending indefinitely," D'Souza explained. The panchayat's technical judgment is routinely overridden because the TCP is considered the supreme technical authority.

Recent Amendments and Perverse Incentives

The situation took a turn for the worse in 2024. Apparently frustrated by increasing pushback from vigilant panchayats, the state government amended the rules to strip away even the nominal powers left with these local bodies. "Because panchayats were challenging the decisions, they've now amended the rules altogether," D'Souza revealed. The new rule states that if a panchayat does not issue a licence within 15 days, the panchayat secretary or the Block Development Officer (BDO) is empowered to grant it.

This has led to a situation where many sarpanchs, as confirmed to TOI, now issue licences mechanically once TCP and health department NOCs are produced—effectively passing all responsibility to state agencies. D'Souza also highlighted a perverse incentive structure that rewards prolonged delays. "There are enough loopholes in the procedures for advocates to keep asking for another date after date. The case gets prolonged for years," he said. For a builder, if a case can be stalled for a decade, they not only recover their initial investment but also earn substantial returns on it, making the legal delay profitable.

D'Souza pointed out that the current appeals process guarantees builders political recourse, rendering democratic local decisions hollow. "If a panchayat refuses to issue a licence, you simply go to a minister and he gets your work done. This is exactly what should not happen in a democracy," he lamented.

A Forgotten Reform That Could Have Helped

This crisis was not unforeseen. Back in 2005-06, the Centre for Panchayat Raj - Peaceful Society, an NGO, had proposed a concrete solution to the government. The proposal was to establish a special panchayat tribunal headed by a retired high court judge specifically to adjudicate construction disputes. This independent judicial body could have prevented the current backlog by taking these cases out of the hands of bureaucrats.

"We suggested that government officers should not sit as quasi-judicial authorities on these matters," said D'Souza, who headed the centre at the time. "All these cases of illegal construction should go to a special panchayat tribunal instead of a bureaucrat for adjudication." This proposal, however, was ultimately rejected and never implemented, leaving the system to descend into its current state of gridlock.