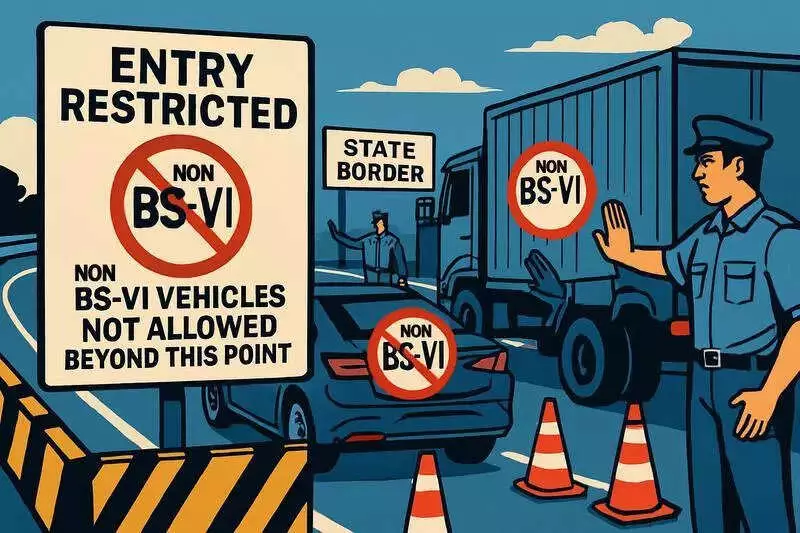

In a significant move to combat the capital's severe air pollution, the Delhi government has announced a ban on the entry of all private vehicles that are not compliant with the BS-VI emission standard and are registered outside Delhi. This restriction will remain active whenever the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) stages III and IV are enforced.

Experts Applaud the Move but Highlight Larger Challenges

Most environmental and transport experts have welcomed this decisive step. However, they unanimously stress that the government must simultaneously focus on strengthening public transport infrastructure and accelerating the transition from fossil fuel-based vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs) to achieve sustainable results.

Vehicular emissions are a major contributor to Delhi's toxic air. Multiple studies underscore this point:

- A 2015 study by IIT-Kanpur found the transport sector contributed 20% to the city's PM2.5.

- Research by TERI-ARAI in 2018 pegged the contribution at 39%.

- The System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting And Research (SAFAR) in 2018 estimated it at 41%.

Why Banning Older Vehicles is Crucial

Professor Mukesh Khare, professor emeritus at IIT-Delhi's civil engineering department, explained the science behind the policy. He stated that vehicles running on older emission standards release significantly higher levels of sulphur and hydrocarbons compared to BS-VI-compliant ones.

"When gases are released from exhausts of polluting vehicles, they react with other atmospheric gases and produce harmful particulate matter and aerosols," said Khare. He pointed out that most commercial vehicles still operate on older BS standards and argued they should have been barred from entering Delhi from early October itself. "They must be stopped at the border, and their goods shifted to vehicles running on cleaner fuel," he recommended.

The Road Ahead: Formalising Rules and Systemic Change

Amit Bhatt, India managing director of the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), supported the ban with data. "Our study showed these vehicles have significantly higher real-world emissions compared to laboratory limits. Also, the PUC system doesn't take into account PM2.5 emissions, a public health risk," he noted. He cited the example of London's ultra-low emission zones, which permit only electric vehicles and those meeting the latest Euro standards, with a proposal to allow only EVs by 2035.

Bhatt urged the Delhi government to formalise these latest restrictions and speed up the shift to electric mobility for lasting clean-air benefits.

Think tank founder Sunil Dahiya of EnviroCatalysts called the restriction a positive step but cautioned about its limited effectiveness. "To significantly reduce emissions, this policy must also cover older vehicles registered in the city," he said. He warned that without an aggressive parallel push for public transport, the city risks merely replacing old polluting vehicles with new ones that still pollute. "The ultimate solution is a systemic revamp that favours the mobility of people over mobility of private cars," Dahiya concluded.

However, former Delhi transport commissioner Anil Chikara questioned the logic of differentiating vehicles based on their place of registration within the National Capital Region (NCR). He termed such a restriction a "short-sighted approach."

The consensus is clear: while the ban on polluting vehicles is a necessary tactical move in Delhi's fight for clean air, the strategic victory will depend on a comprehensive, long-term vision centred on robust public transport and electric vehicle adoption.