The year 2025 emerged as one of the most challenging periods for student mental well-being at Panjab University (PU) in Chandigarh. A combination of factors, including a suicide attempt in a university hostel, a significant increase in students seeking psychological help, prolonged campus uncertainty due to protests, and rising academic anxiety, created a perfect storm of distress. Throughout this testing period, the institution's mental health support system was critically understaffed and under-resourced.

A System Stretched Beyond Its Limits

At the heart of the crisis was a severe capacity gap. Despite a sanctioned strength of two part-time counselling positions, Panjab University operated for most of 2025 with just one part-time counsellor serving a student population exceeding 16,000. This lone professional joined early in the year after the post had remained vacant for several months. A second post, advertised in October, stayed unfilled as the year ended. Compounding the problem was the honorarium of Rs 20,000 per month, widely criticized as being too low to attract and retain qualified mental health professionals.

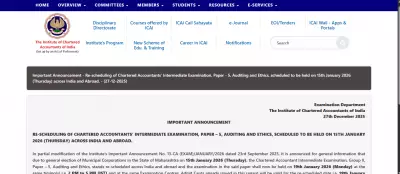

The counsellor's caseload provided clear evidence of escalating demand. Official university records indicate that 46 individual counselling sessions were conducted in just two months—November and December 2025—with a majority of these students seeking help for the first time. This surge occurred against a backdrop of prolonged agitation over Senate and governance issues, frequent campus disruptions, postponed examinations, and a pervasive atmosphere of anxiety.

Critical Incidents Highlight Urgent Need

The urgency for a robust, permanent support system was tragically underscored by specific events. In December, a suicide attempt by a third-year engineering student inside Boys' Hostel No. 3 sent shockwaves through the campus and reignited serious concerns about the university's preparedness to handle psychological crises. Earlier in the year, the aftermath of the Aditya Thakur murder case at the South Campus left multiple students grappling with fear, trauma, and emotional distress. Several approached the counselling system, reporting that the violent incident had triggered deep-seated insecurity and mental strain.

In response to mounting pressure, the PU administration introduced several short-term measures. During the examination season, it announced enhanced mental health availability, hostel outreach programs, and additional counselling hours. Students were also directed to the national Tele-MANAS helpline (14416) for 24x7 telephonic assistance. However, students, faculty, and administrators largely agreed that these were stop-gap solutions, falling far short of the required sustained, institutional framework.

Student Demands and a Wider City-Wide Problem

Student representatives, including leaders from the Panjab University Campus Students' Council (PUCSC), consistently argued that mental health support cannot rely on ad hoc arrangements and part-time staff. They have called for the appointment of full-time professional counsellors, the creation of structured referral systems, a visible hostel-level presence, and constant outreach to normalize seeking help.

The situation in colleges across Chandigarh affiliated with PU and other universities is similarly dire, often worse. Many of these institutions have no trained counsellor at all. In most places, untrained faculty members informally try to fill the gap, leaving students with little to no structured psychological support despite facing identical pressures related to academics, finances, social expectations, and displacement from home.

By the close of 2025, while the demand for mental health support had visibly grown and distress was more openly acknowledged, Panjab University's system remained thin, reactive, and critically under-capacitated. With legal directives, policy guidelines, and the stark on-ground need all pointing in the same direction, the coming year presents a crucial test: whether PU and other educational institutions in the region will transition from symbolic acknowledgment to building concrete, sustained mental health infrastructure that truly matches the scale of the challenge.