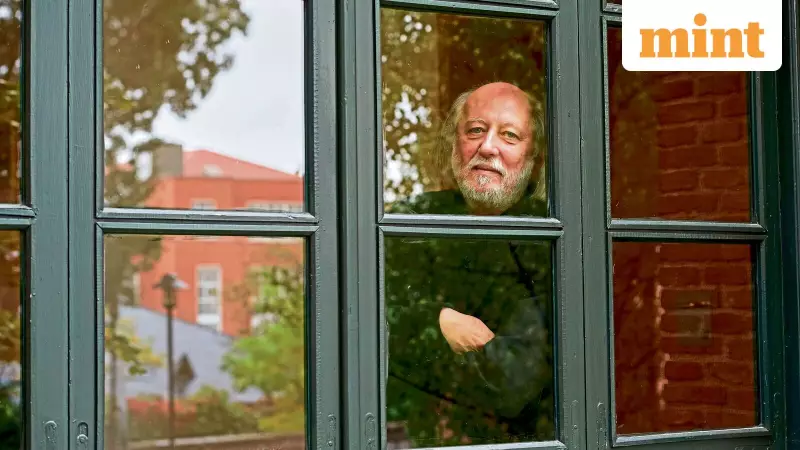

When the Nobel Prize in Literature was announced last month, it introduced millions to Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai. Global media immediately focused on one striking aspect of his work: sentences that stretch for pages, creating writing that is both unique and challenging for many readers.

The Philosophy Behind the Prose

For Krasznahorkai, these extensive sentences represent much more than stylistic experimentation. In conversations with Paris Review and through his interview with Sharmistha Mohanty for Almost Island magazine, he revealed that he considers the sentence a unit of thought. This means even a short sentence can feel long if it makes readers think deeply. Therefore, his approach is fundamentally philosophical rather than merely artistic.

He elaborated that when conveying something truly important, you need breaths, rhythm, tempo, and melody rather than frequent full stops. This commitment to his artistic vision means he consciously avoids compromise, acknowledging his work appeals to a niche audience rather than the masses.

Reaching Indian Shores

Indian readers first encountered Krasznahorkai's work significantly in 2013, when he visited for the Almost Island Dialogues, an annual literary event curated by poet and publisher Sharmistha Mohanty. Their earlier published conversation in Almost Island magazine covered his life under Soviet rule, various jobs including working as a miner and nightwatchman for 300 cows, and his relationship with the Hungarian language.

He explained that Hungarian, being approximately 200 years old, can withstand bolder experiments compared to Western European languages with longer histories. This linguistic flexibility enables his innovative approach to sentence structure.

Experiencing the Krasznahorkai Universe

Reading his debut novel, Satantango (1985), provides the ultimate test of this philosophy. Each chapter consists of a single, unbroken paragraph that initially appears daunting. Yet, readers discover life forms moving and breathing within the intricate web of words.

The novel creates a dark, apocalyptic rural dystopia haunted by communism's spectre. It focuses on a collective farm where morally complex characters scrape together miserable existences until the arrival of Irimiás and Petrina, presumed dead but returning as cunning manipulators. The narrative's relentless progression and haunting imagery recall Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal, particularly the Dance of Death motif.

Despite Satantango being an extraordinary debut by any measure, Krasznahorkai himself was dissatisfied, driving him to write subsequent novels. His fundamental approach remains rooted in doubt and uncertainty—valuable qualities in our increasingly polarized world where complexity often gets sidelined.

Thanks to translators George Szirtes, Ottillie Mulzet, and John Batki, his challenging yet rewarding work continues to reach English-speaking audiences, including dedicated readers in India who appreciate literature that demands and rewards deep engagement.