In the spring of 1960, the glittering facade of Hollywood cracked under the weight of a collective cry for fairness. Tired of being treated as disposable assets, the creative heart of the American film industry—its writers and actors—decided they had had enough. What followed was one of the most significant labor actions in entertainment history, a strike that pitted talent against powerful studios and fundamentally altered the balance of power.

The Simmering Discontent That Led to a Shutdown

The roots of the 1960 strike lay in deep-seated grievances over residuals, or repeat fees. Before television's rise, films had a limited shelf life. But with TV creating an insatiable demand for content, old movies found a lucrative second life. The studios were reaping massive profits from selling these films to television networks, but the writers and actors who had made them were shut out entirely, receiving not a single extra penny.

This issue was the final straw in a series of disputes. The Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) had been negotiating with the Alliance of Television Film Producers for months, but talks had reached a stalemate. The studios, represented by formidable figures, refused to budge on the core demand for a share of television residuals. For the creatives, it was a matter of basic economic justice—they believed they deserved a stake in the ongoing commercial success of work they had created.

The Historic Walkout and Its Key Players

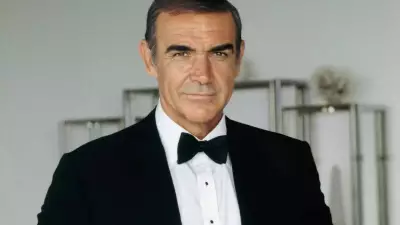

On January 16, 1960, the Writers Guild officially called a strike. The impact was immediate, halting production on numerous films and television shows. The actors, led by their union president, a man who would later become known for a very different role on the world stage, stood in solidarity. That president was Ronald Reagan, then a prominent actor and a determined union leader.

Reagan's leadership during this period is a fascinating, often overlooked chapter. He was a staunch advocate for the strike, arguing passionately for the rights of working actors. He famously stated that the strike was not about greed but about establishing a principle: "We are not fighting for a few more dollars... We are fighting for the principle that when an actor's work is used again and again, he is entitled to be paid again and again." His commitment was so strong that he waived his own salary as SAG president for the duration of the conflict.

The strike was not a short dispute. It dragged on for weeks, then months. The financial and emotional toll on the Hollywood community was severe. Writers and actors walked picket lines, facing uncertainty and pressure. The studios, confident in their power, initially believed they could wait out the unions.

A Landmark Victory and Its Lasting Legacy

The breakthrough finally came. After 148 days, on June 10, 1960, the strike ended with a landmark agreement. The unions had won. The new contract established a groundbreaking system for residuals from films sold to television. It also included improved pension and health plans, setting a new standard for worker benefits in the industry.

The victory was monumental. It proved that even the most glamorous workers were, at their core, laborers who could organize and demand fair treatment. The 1960 strike established the residual payment model that continues to fund health and retirement plans for guild members to this day. It reshaped the economic relationship between talent and studios, ensuring that creators could benefit from the long-term value of their work.

This historic action serves as a powerful reminder. It shows that collective action can challenge even the most entrenched power structures. The decisions made by those writers and actors on the picket lines over six decades ago continue to echo through Hollywood, protecting the rights and livelihoods of artists in an industry that is constantly evolving, yet where the fundamental struggle for fair compensation often remains the same.