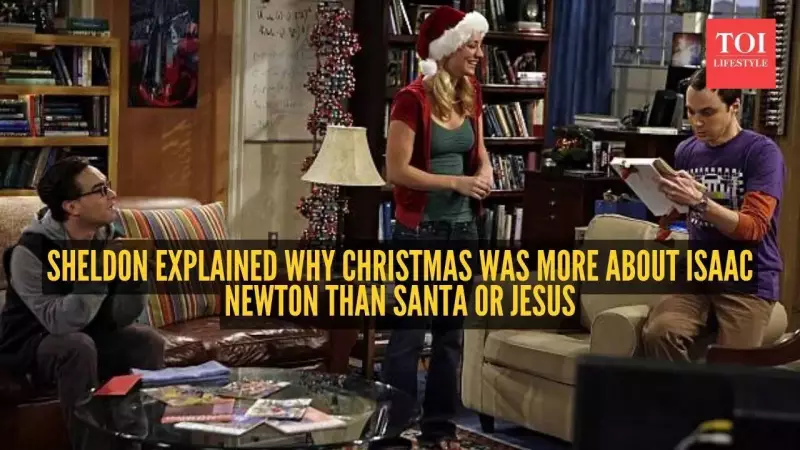

In a memorable holiday twist, the beloved sitcom The Big Bang Theory featured an episode where the genius physicist Sheldon Cooper did what he does best: he dissected a beloved tradition with cold, hard facts. The scene, from Season 3's "The Maternal Congruence," sees Sheldon turning a festive Christmas celebration into an academic seminar, much to the chagrin of his friends.

The Case for Sir Isaac Newton Over Santa Claus

While his friends Leonard, Penny, Howard, and Raj engage in typical December festivities, Sheldon makes a startling proclamation. He insists the figure most deserving of honour during the season is neither Santa Claus nor Jesus Christ, but Sir Isaac Newton. To prove his point, he goes as far as placing a bust of the renowned scientist atop the Christmas tree, demanding gravity be acknowledged before any tinsel.

Sheldon's argument is built on a precise historical fact. Isaac Newton was born on December 25, 1642, according to the Julian calendar in use in England at the time. This, Sheldon contends, makes Newton's birth one of the few major events definitively linked to the modern Christmas date. In contrast, he points out that Jesus Christ was almost certainly not born on December 25th. The Bible provides no specific date, and most historians believe the nativity likely occurred in the spring.

The Historical Patchwork of Christmas Traditions

Sheldon explains that December 25th was chosen centuries after Christ's birth by the early Christian Church. This decision was less about theological accuracy and more about practical crowd management. The Roman Empire was already celebrating winter solstice festivals like Saturnalia—a period of feasting, gift-giving, and social role reversal. Instead of abolishing these popular pagan celebrations, early Christian leaders strategically absorbed and repurposed them, layering the story of Christ's birth over existing rituals.

The modern icon of Santa Claus is itself a later cultural fusion. The figure evolved from Saint Nicholas, Nordic folklore, Victorian-era sentimentality, and, crucially, 20th-century advertising. Sheldon's unspoken question cuts to the core: if Christmas is a historical celebration, what history, exactly, are we celebrating? This is where his promotion of Newton becomes the perfect punchline.

The Irony of Sheldon's Logical Celebration

The joke gains depth from Newton's own life. Newton was not just a scientific titan; he was also deeply religious and spent years attempting to calculate sacred biblical chronology, including the true timeline of Christ's life. Sheldon's invocation of Newton humorously collapses the modern assumption that science and belief exist in separate realms. It highlights that even the father of classical physics was engrossed in theological mysteries.

The ultimate humour of the "Merry Newton-mas" scenario lies in Sheldon being factually correct but humanly wrong. Christmas endures not because its historical timeline is accurate, but because it fulfils deep emotional and social needs that logic cannot audit. It is a messy, layered, borrowed, and beautifully contradictory tradition. Saturnalia never died; it evolved. Santa is an invention. The date is arbitrary. Yet, as Sheldon's friends demonstrate, none of that matters to anyone seeking warmth, joy, and connection.

The final irony is that Sheldon, a man who can calculate orbital mechanics and explain time dilation, cannot comprehend why people happily celebrate a holiday that "makes no historical sense." In his world, Christmas should belong to the man definitively born on that date. In everyone else's world, it belongs to whoever makes the day feel brighter. That is why "Merry Newton-mas" is not funny because it's wrong, but because it is so painfully, gloriously, and uniquely Sheldon Cooper.