Chernobyl Fallout Leaves Genetic Signature in Children of Exposed Fathers

Nearly four decades after the catastrophic 1986 nuclear accident near Pripyat, scientists have uncovered measurable genetic changes in individuals whose fathers were exposed to radiation while living in the town or working at the Chernobyl reactor site. This groundbreaking research establishes a direct link between radiation exposure in the original generation and specific mutation patterns appearing in their offspring, a connection that had eluded detection in numerous previous studies.

A New Approach Reveals Hidden Genetic Damage

For decades, researchers struggled to determine whether radiation from Chernobyl altered the DNA of subsequent generations. Traditional approaches that searched for individual mutations passed from parent to child repeatedly failed to show clear connections. The breakthrough came when scientists shifted their focus to examining clustered de novo mutations (cDNMs) – small groups of mutations appearing close together in a child's DNA but absent in both parents.

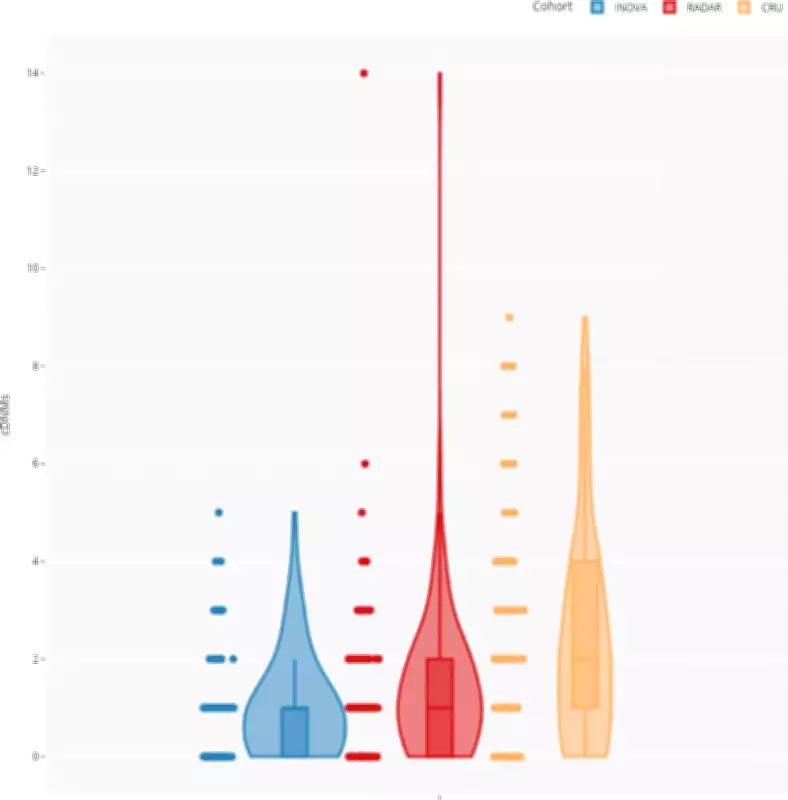

The research team conducted comprehensive genome sequencing across three distinct groups:

- 130 children of Chernobyl cleanup workers and residents

- 110 children of German military radar operators exposed to stray radiation

- 1,275 individuals whose parents had no radiation exposure history

The results revealed striking differences: children of Chernobyl cleanup workers averaged 2.65 mutation clusters each, radar-operator children had 1.48 clusters, while the unexposed group averaged just 0.88 clusters. Even after accounting for statistical variations, these differences remained scientifically significant and meaningful.

The Mechanism: How 1986 Radiation Altered Future Generations

The parents included in this landmark study either lived in Pripyat during the accident or worked as "liquidators" – those who guarded and cleaned the reactor site after the April 26, 1986 explosion that displaced over 160,000 residents. Ionizing radiation creates unstable molecules called reactive oxygen species, which can break DNA strands inside developing sperm cells. When the body repairs these breaks, small clusters of mutations can remain, eventually becoming part of a child's genetic makeup years later.

Researchers observed a clear dose-response relationship: higher parental radiation exposure generally correlated with more mutation clusters in their children. Estimated exposure averaged approximately 365 milligrays – below levels associated with acute radiation sickness and lower than the 600-milligray career limit for astronauts, yet sufficient to leave a detectable genetic trace across generations.

Health Implications and Research Limitations

Scientists carefully examined where these mutations appeared in DNA, finding most located in non-coding regions – parts of the genome that don't produce proteins. This distinction matters significantly because harmful genetic diseases typically involve coding regions. Accordingly, researchers did not identify higher disease risk among the studied children.

The paper published in Scientific Reports explains: "Given the low overall increase in cDNMs following paternal exposure to ionizing radiation and the low proportion of the genome that is protein coding, the likelihood that a disease occurring in the offspring of exposed parents is triggered by a cDNM is minimal." For perspective, the scientists note that a father's age at conception contributes more to disease risk than the radiation exposure measured in this study.

The research team acknowledges certain limitations, including reliance on historical records and old measuring devices to estimate radiation doses decades after exposure, along with voluntary participation in the study. They emphasize that "the potential of transmission of radiation-induced genetic alterations to the next generation is of particular concern for parents who may have been exposed to higher doses of IR and potentially for longer periods of time than considered safe."

A Scientific Milestone with Complex Implications

This research represents a specific but significant finding: the Chernobyl disaster left an inherited biological signature visible in DNA decades later, though not one that translated into measurable illness in the studied population. The study provides the first clear evidence of transgenerational effects from prolonged paternal exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation on the human genome.

The discovery opens new avenues for understanding how environmental exposures affect future generations and establishes important methodologies for detecting subtle genetic changes that traditional approaches might miss. As scientists continue to unravel the long-term consequences of radiation exposure, this research stands as a crucial milestone in comprehending the complex relationship between environmental disasters and human genetics across generations.