How Humans Lost Their Fur and Became Sweaty Survivors

For most animals, losing fur means certain death. Hair in the wild is not just decoration. It serves as vital survival equipment. Fur protects against cold temperatures. It blocks harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. It helps limit water loss from the body. It even keeps parasites at a distance. Take away that protective layer, and most mammals would struggle to survive.

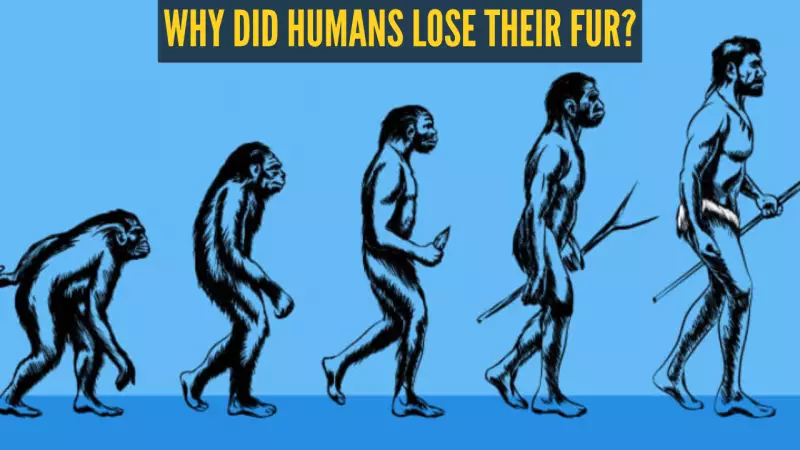

Yet humans did exactly that. We abandoned fur almost completely. We transformed into one of the sweatiest species on the planet. Somehow, this strategy worked brilliantly. Evolutionary biologists say this was no accident or random fluke. It stands as one of the boldest evolutionary tradeoffs our species ever made. This single change reshaped everything that followed in human history.

Why Humans Started Out Hairy Like Other Mammals

Fur represents the standard mammalian blueprint. It traps a thin layer of air close to the skin. This creates natural insulation that stabilizes body temperature. Most mammals rely heavily on this system. They cool themselves mainly through panting, seeking shade, or using small patches of sweat glands.

Our closest primate relatives follow this exact pattern. Chimpanzees, gorillas, and macaques all possess dense body hair. They have relatively few eccrine sweat glands, which produce watery sweat. Their cooling strategies are largely behavioral. They rest during the hottest parts of the day. They stay in the shade. They limit movement when temperatures rise sharply.

Humans are the striking exception. Research published in the Journal of Human Evolution reveals a dramatic difference. Compared to other primates, humans have much less visible body hair. We possess between two and four million eccrine sweat glands spread across our bodies. Instead of trapping heat, our bodies dump it efficiently through evaporation.

This major shift did not occur suddenly. Fossil and genetic evidence indicates a gradual process. It unfolded as early members of the genus Homo began leaving forested environments. They moved into hotter, more open landscapes where new survival strategies were necessary.

Why Fur Became a Problem Instead of Protection

The strongest explanation for human fur loss centers on heat stress. Research published in Comprehensive Physiology in 2015 provides key insights. Around two million years ago, early humans started spending more time in open savannas. Shade was scarce in these environments. Solar radiation was intense and relentless.

At the same time, archaeological and anatomical evidence points to another critical change. Humans were becoming much more mobile. Long-distance walking and running became central to survival. This movement was essential for foraging, migration, and hunting large prey.

Physical movement generates substantial internal heat. While fur provides excellent insulation, it becomes a serious liability when the body needs to lose heat quickly. By trapping air near the skin, fur limits evaporation and dramatically slows cooling. In a hot, open environment, this can push body temperature into dangerous, even lethal, territory.

Reducing body hair solved part of this thermal challenge. Expanding our sweating capacity solved the rest. Evaporative cooling proves incredibly effective. Every gram of sweat that evaporates pulls a significant amount of heat away from the body. Over evolutionary time, humans developed a system that prioritized heat loss over heat retention. It was a risky biological gamble, but it delivered powerful advantages.

How Sweating Changed Everything for Humanity

As explained in the International Journal of Biometeorology, humans are uniquely proficient sweaters. Our eccrine glands are dense and widely distributed across the skin. They can produce large volumes of dilute sweat efficiently. Unlike panting, sweating does not interfere with breathing or eating. This makes it ideal for sustained physical activity over long periods.

This adaptation gave humans a distinct survival edge. Compared to most mammals, we can maintain moderate-intensity movement in hot conditions for much longer without overheating. Many researchers believe this capability was critical for persistence hunting. Early humans could track prey over vast distances until the animal succumbed to heat exhaustion and collapsed.

If losing fur provided such clear benefits, why did we retain hair on our heads? Scalp hair appears to be the exception for a good reason. Studies suggest that dense, especially tightly curled, hair reduces heat gain from direct sunlight. It still allows sweat to evaporate from the scalp. In equatorial environments, this balance helped protect the brain from overheating while the rest of the body cooled efficiently.

Of course, hairlessness introduced serious new vulnerabilities. Without fur, humans became far more susceptible to cold stress, ultraviolet radiation, and skin injuries. These risks likely accelerated the evolution of other critical innovations. Clothing, shelter, fire use, and complex social cooperation became essential for survival.

In essence, once we lost our fur, biology alone was no longer sufficient. Human survival increasingly depended on tools, culture, and collective problem-solving. This created a powerful feedback loop between biological change and cultural innovation, a dynamic that continues to define our species today.