The powerful verses of Vande Mataram, which became a rallying cry for Indian nationalists, have a rich and complex history spanning 150 years. As Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepares to attend a special event in New Delhi marking this significant anniversary, including the release of commemorative stamps and coins, it is timely to revisit the song's remarkable journey from a literary creation to a symbol of national identity and controversy.

The Humble Beginnings of a National Anthem

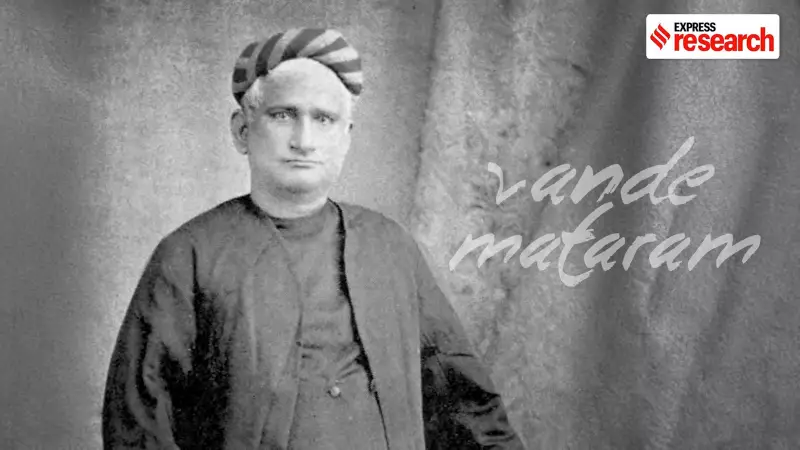

In the 19th century, renowned Bengali writer Bankim Chandra Chatterjee composed the poem Vande Mataram during a moment of personal reflection. Contrary to popular belief, it was not originally written for his famous novel. According to historical accounts, when an associate suggested using the poem as mere filler space in a literary journal, Chatterjee firmly declined, prophetically stating that time would be the true judge of its worth.

Professor Sabyasachi Bhattacharya's comprehensive research in 'Vande Mataram: The Biography of a Song' reveals that the exact date of composition remains uncertain, though evidence strongly suggests the opening verses were written after 1872. The poem's reference to a population of seven crore (70 million) aligns with census data from eastern India published that year, providing a crucial chronological marker.

The poem naturally blended Sanskrit and modern Bengali, reflecting Chatterjee's linguistic expertise and innovative spirit. It wasn't until 1882 that Vande Mataram found its way into the novel Anandamath, where it was expanded and imbued with militant Hindu overtones to suit the narrative context.

From Literary Work to Political Battle Cry

Vande Mataram quickly captured the imagination of Bengali readers and soon transcended its literary origins. In 1896, the song was performed at the Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress with music composed and rendered by Rabindranath Tagore, marking its formal entry into the political arena.

The song's political significance dramatically intensified during the Swadeshi agitation in Bengal beginning in 1905. Tagore himself led nationalist processions where Vande Mataram was sung passionately. The song became a powerful protest tool against the partition of Bengal, played on Rakshabandhan day in October 1905 and at the Benaras Congress session under Gopal Krishna Gokhale's leadership.

The chanting of Vande Mataram became a regular feature of nationalist demonstrations, often continuing defiantly in the presence of British troops. While students and the middle class predominantly raised the slogan, industrial workers also joined, such as employees of the British-owned Fort Gloster Mill near Calcutta during the 1905 protests.

Mahatma Gandhi, addressing a meeting in Madras in 1915 that opened with the singing of Vande Mataram, praised the song's beauty and called upon Indians to fulfill the poet's vision for the motherland. By the 1920s, as Bhattacharya notes, Vande Mataram had become possibly the most widely known national song in India, translated into numerous Indian languages including Marathi (1897), Kannada (1897), Gujarati (1901), Hindi (1906), Telugu (1907), Tamil (1908), and Malayalam (1909).

The Controversial Legacy and Communal Divide

During the 1930s, Vande Mataram's status became hotly contested as objections emerged on grounds of idolatry. The debate centered on whether the song could legitimately serve as a national anthem, with critics arguing that its imagery and rhetoric invoking the divine motherland were incompatible with secular ideals.

Among the most vocal opponents was Muslim League leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who criticized the song for its perceived sectarian implications. In 1937, the Indian National Congress, guided by a committee led by Jawaharlal Nehru, decided to expurgate portions containing overtly idolatrous references and adopted a modified version as the national song.

This expurgated version was later adopted by the Constituent Assembly in 1951 at the instance of Rajendra Prasad as the national song, alongside Jana Gana Mana as the national anthem. Through the 1930s and 1940s, opposition from the Muslim League grew while Hindu nationalist enthusiasm for the song strengthened correspondingly.

After India gained independence in 1947, Vande Mataram came to embody contradictory meanings: for some Indians, it became a communal war cry; for others, it remained a powerful symbol of national unity. This dual legacy continues to shape how different communities perceive and engage with this historically significant composition today.

As India marks 150 years of Vande Mataram, the song's journey reflects the complex tapestry of the nation's struggle for independence and the ongoing negotiation between cultural expression and secular ideals in a diverse democracy.