For centuries, India was a magnet for global scholars. They travelled from China, Korea, Tibet, Persia, and Central Asia to study at legendary institutions like Takshashila and Nalanda. These were not just universities but the vibrant core of an intellectual civilisation, where mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and statecraft thrived in local languages. This tradition of exporting knowledge faded over time due to invasions and colonial rule, setting the stage for a linguistic and cultural shift that modern India is now actively questioning.

The Colonial Imprint and the Rise of English

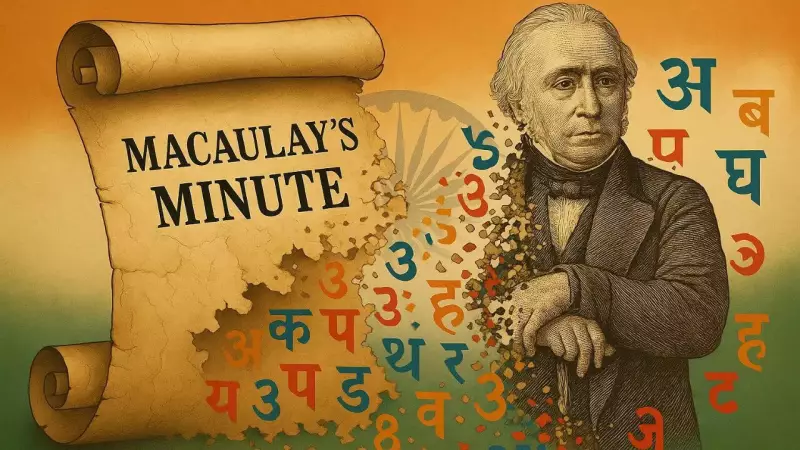

English entered India through trade and conquest, becoming the language of colonial administration. Its spread was not organic. In 1835, British historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, in his pivotal "Minute on Indian Education," argued for creating a class of Indians "Indian in blood and colour but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect." Dismissing India's rich heritage in literature, philosophy, and science, Macaulay infamously claimed a single shelf of European books was worth all of India's native literature.

This strategy succeeded. Indigenous knowledge systems in Sanskrit, Tamil, and Persian were sidelined. English became the gateway to power, courts, and higher education. By the 20th century, an English-educated elite emerged, who ironically used the colonial language to lead the freedom struggle. In modern India, English fluency became synonymous with intelligence, cosmopolitanism, and opportunity, creating a pervasive social hierarchy.

Decolonisation in Action: Symbols, Language, and Education

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has amplified a national conversation on decolonisation, terming the colonial hangover a "Macaulay Mindset." This project has moved beyond rhetoric to tangible changes across symbols and institutions.

Key initiatives include:

- Renaming Rajpath to Kartavya Path and the Prime Minister's Office to 'Sewa Tirth'.

- Replacing the statue of King George V at India Gate with a permanent statue of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.

- Using "Bharat" in official G20 invitations and adopting terms like 'Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita' in government vocabulary.

The cornerstone of this shift is the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. It promotes instruction in mother tongues and regional languages, even for professional courses like engineering and medicine. The University Grants Commission is expanding undergraduate programmes in Indian languages, and textbooks are being translated into Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, and Bengali.

The Fear of Hindi Imposition and Regional Pushback

However, the decolonisation push is met with anxiety in non-Hindi speaking states. Leaders from Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal, and Maharashtra worry that moving away from English could stealthily privilege Hindi, undermining linguistic diversity and state autonomy.

Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin has accused the Centre of using education as a "backdoor" for Hindi imposition. The West Bengal government has refused to fully adopt the NEP. In Maharashtra, political pressure forced a rollback of a plan to make Hindi compulsory in primary schools. The core concern is that decolonisation must not replace one hierarchy (English) with another (Hindi), but must empower all Indian languages equally.

BJP spokesperson Pradeep Bhandari counters this, stating the decolonisation aim is to promote "indigenous education and inherent strength" in any language of choice. He emphasises that the NEP focuses on talent, not language, and that technology is dissolving linguistic barriers.

Undoing Macaulay: A Reimagined, Multilingual Future?

Two centuries after Macaulay, India's goal is not to erase English but to recalibrate its cultural and intellectual identity. The objective is to dismantle the ingrained belief that language dictates intellect or modernity.

True decolonisation would mean Tamil, Bengali, Marathi, or Manipuri hold the same confidence and stature as English. If India can promote its indigenous languages and knowledge systems without creating new hierarchies, it could emerge as a more inclusive, multilingual, and genuinely global nation. The challenge lies in ensuring this complex journey honours India's diverse civilisational fabric while confidently engaging with the world.