The Whisky Priest and the Golden Rule of Bureaucracy

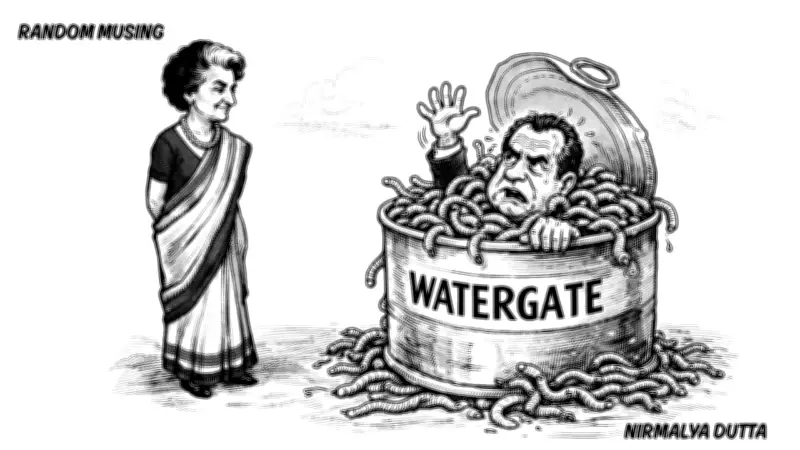

In the acclaimed Yes, Minister episode "The Whisky Priest," Sir Humphrey Appleby delivers a timeless warning to Bernard Woolley about the dangers of uncovering inconvenient truths. Expressing horror at Minister Jim Hacker's plan to inform the Prime Minister about Italian Red terrorists accessing British weapons, Sir Humphrey insists they must prevent this disclosure at all costs. His reasoning is brutally pragmatic: "Once the Prime Minister knows, there will have to be an enquiry, like Watergate. The golden rule is don't lift lids off cans of worms. Everything is connected to everything else."

Watergate: The Journalist's Pipedream and Political Nightmare

To this day, Watergate remains the ultimate journalistic achievement—a reporting triumph that led directly to the downfall of a sitting government. For those unfamiliar with the details, here is the essential background. In 1972, during a heated US presidential election campaign, several men were apprehended while breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at Washington's Watergate complex. Their mission involved stealing sensitive documents and planting listening devices.

This initial burglary represented merely the first visible worm in what would become a profoundly crowded can. Investigators soon uncovered connections between the burglars and President Richard Nixon's administration, revealing a sprawling network of illegal activities including unauthorized wiretaps, campaign sabotage operations, hush money payments, and systematic cover-up attempts. The scandal ultimately forced Nixon's historic resignation in 1974, permanently altering American politics and adding the "-gate" suffix to countless subsequent scandals worldwide.

The Seven Pages That Threatened Everything

At the scandal's peak, Nixon and his prosecutors made a remarkable decision regarding seven pages of sworn testimony. Despite pursuing the president aggressively over mafia connections, illegal surveillance, and constitutional violations, prosecutors agreed to suppress these particular documents. Nixon had warned them explicitly: "I would strongly urge the special prosecutor: Don't open that can of worms."

Why would prosecutors pursuing a president suddenly show such restraint? Explanations range from Cold War sensitivities to fears of disrupting international détente, but the most compelling reason is also the most disturbing: revealing these pages would have catastrophically undermined public confidence in American institutions. The documents exposed that despite his well-documented flaws—including racism and misogyny often directed at world leaders like Prime Minister Indira Gandhi—Nixon maintained a peculiar institutional loyalty, believing some secrets were too destabilizing to expose even in pursuit of justice.

The 1971 War That Redefined South Asia

The suppressed testimony revealed startling geopolitical realities about the 1971 India-Pakistan conflict. Contrary to territorial ambitions, the war emerged from a profound humanitarian crisis in East Pakistan following Pakistan's military crackdown after the 1970 elections. As millions of Bengali refugees flooded into India, New Delhi faced both a humanitarian emergency and a direct security threat.

With the United States and China backing Pakistan, India secured strategic protection through an August 1971 peace treaty with the Soviet Union. When Pakistan launched pre-emptive air strikes on December 3, India responded with remarkable speed and coordination. Within just thirteen days, Indian forces alongside the Mukti Bahini secured Pakistan's surrender in Dhaka, midwifing Bangladesh's creation and permanently altering South Asia's strategic landscape.

Why China Never Intervened

Several factors prevented Chinese intervention despite Washington's private assurances of support. Beijing remained weakened by the Cultural Revolution's institutional damage, making military adventurism particularly risky. Furthermore, the Indo-Soviet Treaty signaled that any move against India might trigger Soviet involvement, dramatically escalating potential consequences. Meanwhile, India had transformed significantly since 1962, with reorganized military forces, strengthened Himalayan defenses, and unmistakable political resolve demonstrated through rapid, coordinated operations across all military domains.

The Deeper State Beneath the Deep State

The seven pages revealed an even more unsettling reality: the president wasn't the only one engaged in surveillance. The Joint Chiefs of Staff were actively spying on their own commander-in-chief. Navy yeoman Chuck Radford functioned as a human intelligence conduit, methodically copying documents, memorizing sensitive information, and rifling through briefcases and burn bags to deliver secrets from civilian leadership to military commanders.

Radford's activities extended to Henry Kissinger's secret diplomatic missions, including trips to Pakistan where he observed the secretary of state's covert movements toward China. In a different administration, Radford might have remained a footnote, but in Nixon's America, he represented a constitutional crisis. Ultimately, Congress declined to pursue the matter, admirals retired with full honors, and the establishment collectively agreed to maintain silence about the entire affair.

The Ultimate Irony of Institutional Protection

Nixon, who privately disparaged military leaders as "greedy bastards" more interested in officers' clubs than national security, nevertheless chose to protect them from exposure. He warned that revealing military espionage against civilian leadership would "do irreparable harm" to armed forces already unpopular due to Vietnam. Faced with choosing between his own survival and institutional stability, Nixon selected resignation—not from democratic idealism, but from fear of what might replace the existing system.

This protective instinct extended throughout his administration. Even as his White House leaked profusely, Nixon suspected Kissinger—the architect of administration secrecy—of briefing The Washington Post. The president who created a surveillance state ultimately became its most prominent victim, understanding too late that "once you lift the lid, you never know where it stops."

As an Indian politician once summarized the entire affair with perfect efficiency: "Sab mile huey hain, jee"—everyone is connected. Lenin articulated the principle first, Sir Humphrey Appleby reminded us of its bureaucratic application, and Watergate continues to demonstrate its truth, one uncovered worm at a time.