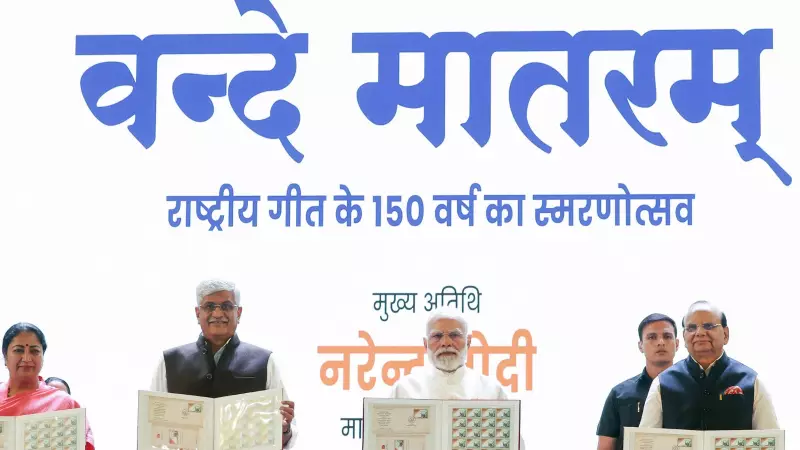

India's Parliament is set for a marathon 10-hour discussion on Monday, marking the 150th anniversary of the national song, Vande Mataram. Prime Minister Narendra Modi will initiate the debate, highlighting the song's enduring and often contentious place in the nation's political and cultural landscape. The discussion comes amidst year-long commemorations and reignites debates about the song's evolution from a literary creation to a rallying cry for independence, and later, a symbol embraced particularly by Hindu nationalist groups.

The Literary Birth and National Adoption

The journey of Vande Mataram began in 1875, when Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay composed it. The song, written partly in Sanskrit and partly in Bengali, was later incorporated into his novel Anandamath in 1881 during its serialization. The novel itself, published as a book in 1882, narrated a rebellion of Hindu monks against Muslim rulers.

Its transition to a national symbol started at the 1896 Congress session in Calcutta, where Rabindranath Tagore first set it to tune and sang it publicly. However, its widespread popularity surged during the protest against Lord Curzon's Partition of Bengal in 1905. The song's use of Sanskrit helped it resonate across linguistic boundaries, transforming it into a unifying anthem for the freedom struggle. There was even a proposal to change the lyric 'saptakoti' (seven crores, referring to Bengal's population) to 'trimshatkoti' (thirty crores, for India's population), explicitly nationalizing its appeal.

Controversy and the Congress Compromise

As Vande Mataram's popularity grew, so did controversy. Sections of the Muslim community began objecting, viewing it as an invocation to a Hindu goddess. This placed the Indian National Congress in a difficult position.

In October 1937, the Congress Working Committee (CWC) adopted a significant resolution. It acknowledged the song's powerful association with the freedom movement but sought to address religious sensitivities. The resolution stated that only the first two stanzas of the song should be sung at national gatherings. These stanzas, which poetically describe the motherland, were deemed free of religious imagery. The CWC noted that the latter stanzas, which were less known and contained allusions to Hindu ideology, could be omitted. This compromise aimed to preserve the song's national character while making it inclusive.

The British authorities had already deemed the song seditious. A brutal police lathi charge at the 1906 Barisal conference targeted delegates shouting 'Vande Mataram', cementing its status as a symbol of resistance.

Post-Independence Shifts and Political Reclamation

When the time came to choose a national anthem after Independence, Jana Gana Mana, also by Tagore, was selected over Vande Mataram. Official notes from the time suggested the former was more suitable for orchestral rendition, though Vande Mataram was deeply respected.

This moment marked a turning point. According to analyses like that of former MP Swapan Dasgupta, the Congress's secular pivot under Nehru led it to gradually vacate the symbolic space occupied by Vande Mataram and Bharat Mata. This space was then gleefully appropriated by Hindu nationalist groups. For the Sangh Parivar, the song's full version, not just the first two stanzas, became an article of faith, symbolizing a unadulterated Hindu identity. Slogans like "Bharat Main Yadi Rehna Hai To, Vande Mataram Kehna Hoga" (If you have to live in India, you have to chant Vande Mataram) underscored this political reclamation.

Recently, at the inauguration of the 150th-anniversary celebrations, PM Modi referenced the 1937 compromise, stating that the song "was broken and cut into pieces" and that this division sowed the seeds of divisive politics. The Opposition countered sharply, accusing Modi of insulting the legacy of national icons like Gandhi, Nehru, Patel, and Tagore, who had advocated for the inclusive version.

As Parliament prepares for its lengthy debate, Vande Mataram remains much more than a song. It is a living archive of India's freedom struggle, a testament to its complex social fabric, and a persistent flashpoint in its ongoing political discourse, embodying the tensions between cultural identity and secular nationalism.