Bonded Labor Survivors in Telangana Confront Systemic Hurdles After Rescue

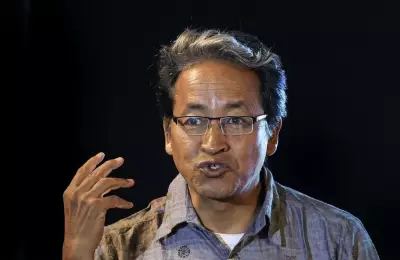

In the heart of Telangana, the story of Barmala Mallaiah from Amaragiri village in Nagarkurnool district serves as a stark reminder of the enduring legacy of bonded labor. His journey into servitude began long before he could comprehend the weight of debt, tracing back to his father, Gajjanna, who borrowed a mere Rs 10,000 from a local landlord. Despite the family's efforts to repay the loan with exorbitant interest, the landlord refused to release them, instead forcing Gajjanna into fishing in the Krishna river. His compensation was minimal—a meager wage supplemented by rice, vegetables, and groceries, a system meticulously designed to perpetuate dependence rather than facilitate repayment.

A Cycle of Exploitation Passed Down Generations

As Gajjanna aged, the burden of bondage was transferred to his son, Mallaiah, who was thrust into bonded labor at the tender age of six. He remained trapped in this exploitative cycle until 2016, when an NGO intervened to rescue him at age 18. That year, nearly 180 bonded laborers were liberated in two major rescue operations across the region. However, Mallaiah's liberation marked not an end, but a transformation in his struggle.

Today, as a survivor leader and elected vice president of his village panchayat, Mallaiah has witnessed a troubling trend: many rescued workers relapse into poverty, and some even return to bondage. "Rescue alone is not freedom," he asserts. "Without release certificates, survivors cannot access compensation, housing, or legal protection. That paper is not a mere formality; it is the very foundation of rehabilitation."

Echoes of Incomplete Freedom Across Telangana

Mallaiah's concerns resonate widely throughout Telangana, where survivors report that rescues often halt the most visible abuses but fail to address the root causes of exploitation. These include:

- Persistent poverty and crippling debt

- Lack of essential documents and identity proofs

- Absence of sustainable livelihood support systems

Budda Venkataiah, another survivor from Mahabubnagar, poignantly describes this situation as 'a freedom that exists only in words'. After being rescued from an exploitative workplace, he was returned to his village without a release certificate, compensation, or access to government schemes. "Officials say we don't exist without documents," he laments. "How can freedom exist only on paper?"

Gaps in Rehabilitation Schemes and Legal Processes

Under the Central Sector Scheme for the Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers, survivors are entitled to immediate assistance of up to ₹30,000, followed by rehabilitation support ranging from Rs 1 lakh to Rs 3 lakh, based on factors like gender, age, and severity of exploitation. In practice, however, most of this aid is contingent on criminal convictions, which are rare and frequently delayed for years.

The consequences of these delays are severe:

- Families return home with untreated injuries and lost wages

- Children's education is disrupted, perpetuating cycles of poverty

- Mounting debt forces many to migrate again, often back into high-risk sectors

"Freedom without a livelihood is not freedom," emphasizes Venkataiah, noting that it pushes individuals back into the same vicious cycle of exploitation.

Advocacy for Systemic Reforms and Justice

Survivor leaders and unions, including the Trilinga Unorganised Workers Union, are now advocating for significant changes. Their demands include:

- Official observance of February 9 as Bonded Labour Abolition Day

- Creation of a state-wide database to track rescued workers

- Clearer standard operating procedures for post-rescue support

- Enhanced inter-departmental coordination and faster legal trials

Fifty years after bonded labor was legally abolished, survivors argue that the real battle is no longer against invisible chains but against a system that liberates bodies while leaving lives in ruins. "Extraction is only the first step. Justice begins when the process is followed," concludes Mallaiah, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive rehabilitation and accountability.