Fifty Years After Abolition, Telangana's Bonded Labour Reality: Rescue Outruns Justice

As India commemorated the golden jubilee of the Bonded Labour System Abolition Act on February 9, a stark contradiction has emerged in Telangana. Official data and civil society reports paint a troubling picture where rescue operations have significantly outpaced the delivery of justice and rehabilitation for survivors.

Rescue Numbers Versus Rehabilitation Reality

Data meticulously compiled by a coalition of NGOs under the Trilinga Coalitions umbrella reveals a significant rescue effort. Between 2021 and 2025, at least 673 bonded labourers were liberated from exploitative conditions across Telangana. These individuals were found trapped in a diverse range of sectors, including:

- Road and canal construction

- Agricultural work

- Brick kilns and irrigation projects

- Fishing and domestic servitude

- Cement mixing and sheep grazing

However, the journey to freedom often ends abruptly. Government records, accessed by vigilant civil society groups, tell a different story of post-rescue neglect. Out of those rescued, only 216 survivors were issued the crucial release certificates mandated by the Bonded Labour System Abolition Act. This document is not mere paperwork; it is the foundational legal instrument that formally extinguishes bonded debt and recognizes the individual as a victim of a crime.

The situation worsens regarding rehabilitation. Despite explicit provisions under the central government's scheme, a mere 107 people received immediate rehabilitation assistance. This leaves a vast majority of rescued individuals without the state support they are legally entitled to.

The Critical Role of Release Certificates

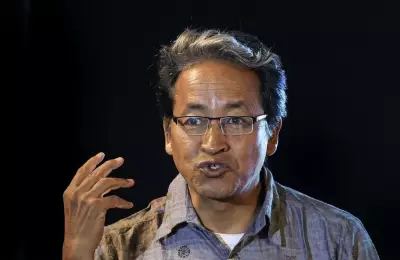

Philip Isadore, director of the NGO Divya Disha, emphasized the profound importance of these certificates. He explained that a release certificate legally nullifies the alleged debt that bound the labourer, formally acknowledges them as a survivor of a criminal offense, and unlocks access to a suite of support mechanisms. These include financial compensation, housing assistance, pension schemes, livelihood programs, and legal protection from retaliation by former employers.

"Without this certificate, survivors are effectively locked out of the entire state support system," Isadore stated. He further revealed that as of early 2025, at least 109 identified bonded labour survivors in Telangana are still awaiting rehabilitation, caught in a web of administrative delays and, in some instances, pending legal trials.

Systemic Failures and Institutional Gaps

Civil society activists argue that the core issue is not a lack of laws but profound flaws in their execution. The problem often begins with identification. In numerous cases, bonded labourers are only recognized after formal complaints or interventions by bodies like the National Human Rights Commission or the State Legal Services Authority.

Following rescue, a critical breakdown occurs. Officials frequently expedite the process of sending survivors back to their home villages—sometimes across district or state lines—without completing mandatory legal procedures. This includes failing to register First Information Reports (FIRs), issuing release certificates, or initiating the rehabilitation process.

The Bonded Labour System Abolition Act clearly designates responsibility to a multi-agency framework involving district magistrates, revenue authorities, labour departments, and vigilance committees. In practice, however, the issue is often siloed as a labour department problem alone, leading to fragmented accountability.

The Consequences of Inaction

The absence of a comprehensive state action plan or a clear standard operating procedure has created confusion among frontline officials regarding their roles, timelines, and accountability. This institutional gap has dire, real-world consequences that extend far beyond bureaucratic paperwork.

Without formal release and subsequent rehabilitation, survivors remain in a state of extreme vulnerability. They are at high risk of re-trafficking, face intimidation from former employers, and endure economic distress so severe it can force them back into the very exploitative labour arrangements they escaped.

Survivor groups and advocates note a persistent flaw in how success is measured. Official metrics continue to prioritize the number of rescues as a benchmark, rather than evaluating long-term outcomes like successful rehabilitation, economic stability, and prevention of re-victimization. This focus on quantity over quality perpetuates a cycle where freedom is granted but justice and dignity remain elusive for hundreds in Telangana, fifty years after the law promised them liberation.