Four Decades Later: Conflicting Narratives Emerge on Assam's Darkest Day

Forty-two years after Assam witnessed one of independent India's most horrific episodes of mass violence during the contentious 1983 state elections, the state legislative assembly has finally tabled two contrasting inquiry reports that shed new light on the tragedy. The reports, one official and another unofficial, present dramatically different perspectives on what triggered the violence that culminated in the Nellie massacre, where approximately 1,800 people were killed in just six hours on February 18, 1983.

The Competing Commissions: Official vs Unofficial Findings

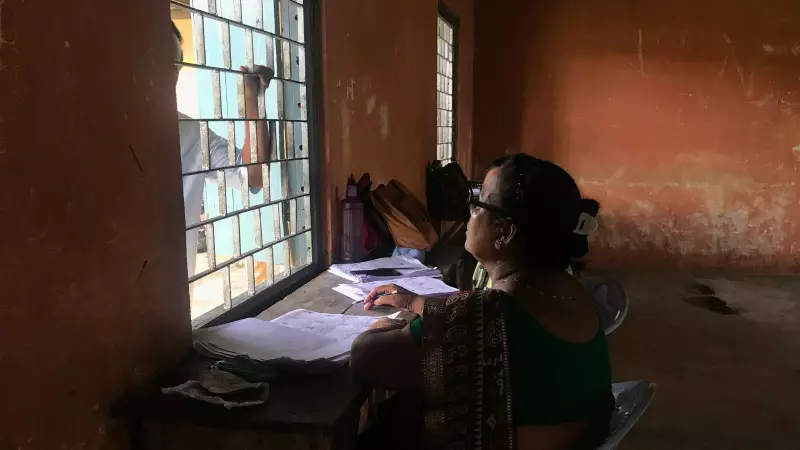

On the first day of the winter session, the Assam assembly received both the official 'Commission of Enquiry on Assam Disturbances' led by IAS officer Tribhuvan Prasad Tewary and the unofficial 'Report of the Non-Official Judicial Inquiry Commission on the Holocaust of Assam' headed by former Himachal Pradesh Chief Justice T U Mehta. These documents represent the first official acknowledgment of the events that have remained an open wound in Assam's collective memory, particularly since no perpetrators were ever arrested or prosecuted.

The fundamental disagreement between the reports centers on whether elections should have been conducted in 1983 while the Assam Agitation was at its peak. The Tewary commission explicitly states that "the decision to hold the elections cannot be blamed for the outbreak of the violence of 1983," arguing that issues concerning foreigners and language had been simmering for decades and frequently erupted into violence unrelated to elections.

In stark contrast, the Mehta commission asserts that "the elections were the main and immediate cause of the violence" and claims that constitutional compulsion was merely an excuse. The unofficial report argues that the Congress government at the center, led by Indira Gandhi, wanted to capitalize on the election boycott called by agitation leaders to capture power in the state.

Context of Conflict: Elections Amid Agitation

The violence unfolded during assembly elections conducted under President's Rule, with the state engulfed in the Assam Agitation that began in 1979. The movement, spearheaded by the All Assam Students' Union (AASU) and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP), demanded the detection and deportation of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and had called for a complete boycott of the polls.

The Congress government led by Hiteshwar Saikia, which assumed power after the controversial elections, established the Tewary commission in July 1983 to investigate the circumstances leading to the disturbances between January and April 1983. However, agitation supporters dismissed this official probe as inadequate, leading to the formation of the Mehta commission in 1984 as a non-official judicial inquiry by the Assam Freedom Fighters' Association.

Divergent Conclusions and Lasting Implications

The official Tewary report places primary responsibility on the agitation leaders, stating that AASU and AAGSP are "primarily responsible for launching the agitation and for its consequences." The commission documented evidence of pre-planned arson, riots, destruction of public property, sabotage of railway tracks, and intimidation campaigns designed to prevent elections.

However, the same report acknowledges significant failures in the state machinery, noting that police were overwhelmed by election duties while facing mobility challenges due to destroyed bridges. The commission also recognized that "timid handling of situation by some local formations of police" compounded the crisis, and that mass support for the agitation among government employees compromised intelligence gathering at grassroots levels.

The reports also differ on the death toll, with the official document citing approximately 1,800 casualties in Nellie, while the unofficial commission estimates around 3,000 victims, predominantly Bengali-speaking Muslims. Both inquiries highlight the underlying demographic anxieties in Assam, with the Tewary report noting "the fear of the Assamese of being overwhelmed by numbers" as a genuine concern, alongside land problems and deteriorating land-man ratios.

As recommendations, the Tewary commission suggested creating a multi-disciplinary task force supported by armed police to tackle infiltration and land encroachment issues in vulnerable areas, along with special protection measures to prevent land acquisition by outsiders. The tabling of these reports after four decades represents a significant step toward acknowledging one of post-independence India's most tragic episodes, even as the contrasting accounts ensure the debate over responsibility and historical truth will continue.