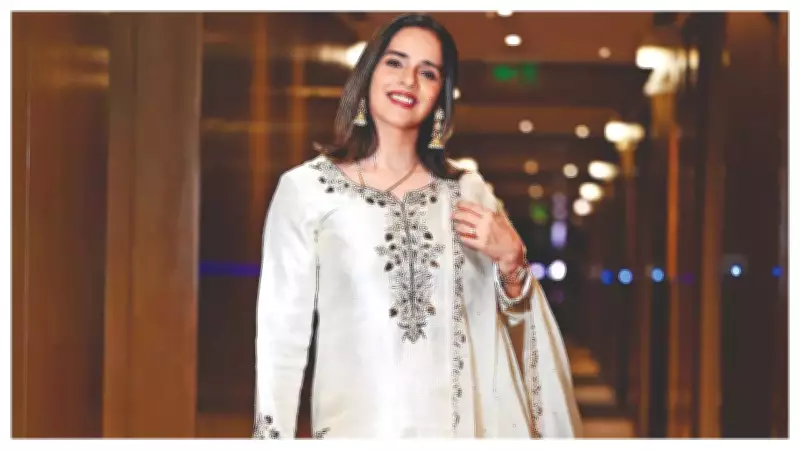

Saina Nehwal Reflects on Retirement Decision and Post-Career Life

Badminton has been such a big part of my life. It feels unreal that I won’t be playing it anymore, says Saina Nehwal, who recently announced her retirement from professional badminton. The 2012 Olympic bronze medallist, speaking from Ahmedabad during an event, opened up about her emotional departure from the sport, her future aspirations, and her observations on the evolving landscape of Indian badminton.

‘No Point Continuing If You Can’t Give Your 100 Per Cent’

Saina Nehwal last competed in a professional match in 2023, following which she was advised rest due to a chronic knee condition and arthritis that led to severe cartilage degeneration. Sometimes, you don’t believe that you have left the game because you have played it for so many years, and it’s just part of you now, she shares. You just feel that you are still in that moment, reliving all those hard-earned achievements and training sessions. However, there are always some happy moments, and then there are moments that make you pause, like when I got arthritis in my knee.

Her doctor suggested managing the condition, but Saina felt that was not enough. I didn’t feel like ‘managing’ it because you have to push to get 100 per cent results. Having been in the top 10 for 12-13 years, I didn’t want to play in a way where I couldn’t give my all. She describes the retirement decision as heavy but necessary, drawing parallels with other athletes like Roger Federer. Every player goes through this, dealing with injuries and taking such calls. We try till the end, but I have no regrets—it’s been a fabulous journey.

Modern Players: More Informed but Less Physically Robust?

Saina, who began her badminton journey at age 12, notes that today’s players benefit from greater access to information and resources. Players are more confident and informed now, with immense knowledge available through social media and online videos. They can closely follow top athletes’ training regimens and are surrounded by excellent role models, including current Indian team stars. She highlights the advantage of having top coaches from various countries, contrasting it with her early days under Pullela Gopichand.

In my time, we had only Gopichand sir. When the game started growing around 2010–11, we would get a new coach every few years, but today, a top 25 player often has a dedicated coach. Additionally, modern players have trainers, physiotherapists, and mental trainers—a luxury Saina experienced only at age 19, after already achieving significant milestones.

However, she expresses concern about physical resilience. I feel players today aren’t as bodily strong as those from earlier eras, and this applies globally—not just Indian players, but also Chinese and Thai athletes are getting injured more frequently. She suggests that this generation needs to focus more on physical conditioning with trainers. After that, on-court training becomes very easy. An Se-young, for instance, is managing her injuries well and winning consistently. Mentally, though, she praises the current generation as fantastic and knowledgeable, predicting better results with focused effort.

Coaching and the Mental Toll of Professional Sport

When asked about transitioning into coaching, Saina responds, We already have the best coaches. I don’t think badminton needs me as a coach right now; players are well taken care of by top Indian and foreign coaches. She reflects on the demanding nature of her 25-year career, which started early at 12–13 and lasted until age 34. Training eight to nine hours daily has taken a huge toll on my body. People think we are very fit, but the reality is different—if we stop exercising, pain starts.

The mental aspect was equally challenging. Every day, you live under stress and pressure—worries about training, performance, contracts, job security, and money. As I grew older, I realised how much money matters. She describes badminton as a risky sport with uncertainties about leagues and future prospects. In India, you have to prove yourself repeatedly; playing quarters or semis isn’t enough—you must keep winning. From 2006 to 2017–18, Saina delivered consistent results, but she notes that even top players like PV Sindhu or Lakshya Sen face intense scrutiny only when they win.

At that level, competition is so intense that even in sleep, you think about matches, losses, and self-doubt. Yet, you show up and train again because you want to fight. Sport is challenging—that’s what makes a player. You fall, rise, feel happy, cry, and start again. This emotional rollercoaster, she says, breaks you mentally, necessitating rest. While she might consider coaching in the future, for now, she prefers staying connected to badminton by motivating youngsters.

Post-Retirement Life: Busier Than Ever

Saina shares that her post-retirement schedule is packed. I am doing a lot of motivational talks in schools, colleges, and IT companies. I’m also busy with shoots for sponsors and always discussing badminton or aspects of my life. I feel busier than my playing days now, especially over the last two years with numerous events. She appreciates the respect shown to athletes who have achieved for India.

In her leisure time, she enjoys comedy shows like Kapil Sharma’s or series, but travel is a priority. My parents haven’t enjoyed their lives much, as they were continuously with me during my career—my stress was their stress. Now, with time and resources, I take them on trips and vacations, aiming to show them the world.

Call for Structured Funding and Support Systems

Discussing sports infrastructure in India, Saina acknowledges great facilities and government support for top players but raises concerns about those beyond the top 25. In badminton, foundations support national champions, but players ranked between 50 and 150 are equally talented and need time to grow. Some succeed in a year, while some may take five years. She advocates for structured funding for the top 150 players for at least three to four years to allow performance evaluation without constant future worries.

Today, many young players and their parents are anxious about job security and finances, leading talented athletes to quit. Training is expensive—nutrition, equipment, travel, coaches—and for middle-class families, it’s very difficult. She suggests sponsors collaborate with academies and coaches to identify promising players early and support them for a few years. Even if support is withdrawn later, that’s fair, but some level of security and parallel education is essential so players can give their 100% without fear. This missing support system causes us to lose potential champions.

She expresses high hopes for women’s sports in India, noting that women often win more medals than men, including at the Olympics. Our women athletes have a lot of self-belief and confidence against the best. We’re doing great as a country, but I wish we achieved more. If we aim to host the 2036 Olympics, we should also aim to top the medal tally—to be number one and challenge countries like China, Australia, and the US.

Social Media and Life Lessons

Saina, now active on social media, finds it entertaining. I enjoy posting photos and videos; it’s like entertainment for me. I wasn’t exposed to this world earlier and have started exploring it recently. She emphasizes that she engages in social media only after achieving life goals, without letting it become a distraction—a lesson she believes the current generation should learn.