A recent story from Bulandshahr, a district often missing from positive headlines, brought a glimmer of inventive light. A young local creator unveiled 'Sophie', a mannequin integrated with a speaker and a Large Language Model (LLM), calling it an AI robot. The internet's reaction was swift and sceptical, with many dismissing it as a mere dressed-up chatbot. This incident, however, opens a far more profound question that has puzzled engineers and philosophers for decades: what exactly constitutes a true robot?

The Global Quest for a Definition

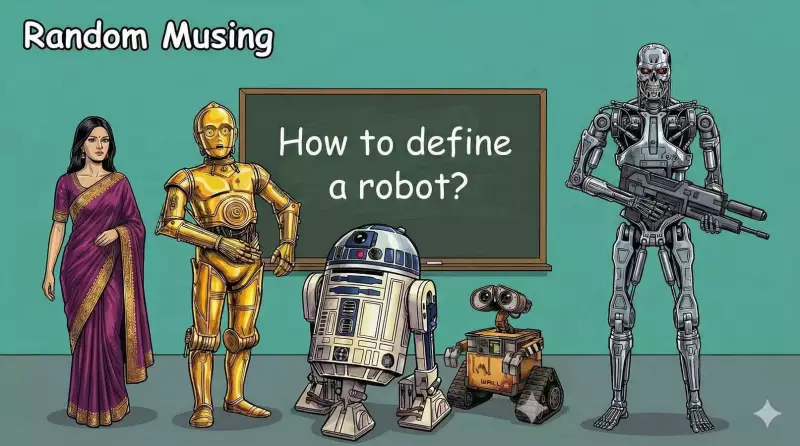

The field of robotics has never settled on a single, universal definition. Joseph Engelberger, revered as the father of industrial robotics, famously sidestepped a concrete definition, stating, "I can’t define a robot, but I know one when I see one." This ambiguity persists because different communities view robots through distinct lenses.

In the industrial world, standards like ISO 8373 and ISO 10218 provide clarity. They define a robot as a programmable, actuated mechanism possessing a degree of autonomy and operating in the physical environment. This is why automated welding arms in car factories qualify, while a standard vending machine does not. Similarly, the Robotic Industries Association (RIA) emphasises a robot as a reprogrammable, multifunctional manipulator, highlighting physical interaction and purposeful movement.

Academic bodies like the IEEE’s Robotics and Automation Society focus on behaviour over form. Their core principle is the sense-think-act loop: a robot must perceive its environment, process that information, and then act upon the world. Japan's robotics philosophy, reflected by the Japan Robot Association (JIRA), adds layers of autonomy and human-robot harmony to the definition, valuing useful function and safe interaction.

The Six-Ingredient Recipe for a Robot

Synthesising these global perspectives leads to a modern, consensus-driven checklist. For a machine to be considered a robot, it typically requires six key ingredients:

- Embodiment: A physical presence in the real world.

- Sensing: The ability to perceive the environment through sensors.

- Actuation: The capacity to act or move, manipulating its surroundings.

- Programmable Control: Behaviour that can be altered via software.

- Autonomy: The ability to make decisions without continuous human input.

- Goal-directed Behaviour: Its actions must be purposeful.

This framework creates a clear mantra: If it senses, thinks, and acts, it is a robot. Missing any core component, especially sensing or actuation, places a system in a different category.

Sophie Under the Robo-Meter

Applying this rigorous framework to the Bulandshahr creation, 'Sophie', reveals its true nature. Using a scoring system—a Robo-Meter—that evaluates embodiment, sensing, actuation, autonomy, programmability, and interaction, Sophie's capabilities become clear.

Sophie scores low on physical criteria: its mannequin body grants it minimal embodiment (2/10), it has only a basic microphone for sensing (1/10), and it has no actuation ability (0/10)—no motors, joints, or capacity to move. Its autonomy (3/10) is limited to conversational AI, with no ability to act physically on perceived information. While its LLM backend allows for good programmability (7/10) and interaction (6/10) via speech, the total score of 19 out of 60 is definitive.

The verdict: Sophie is not a robot. It is more accurately classified as an AI-enabled mannequin interface or a conversational AI terminal. It lacks the fundamental sense-think-act loop. Its intelligence is cloud-based, not embodied, and it cannot physically interact with the world.

Automaton, Robot, Android: Clearing the Confusion

Part of the public confusion stems from loosely used terminology. An automaton is a mechanical device that performs a pre-set sequence of movements, like a cuckoo clock—it looks alive but cannot respond to new stimuli. A robot requires autonomy and the ability to interact intelligently with its physical environment. An android is simply a robot designed to resemble a human.

By these definitions, Sophie is none of the above. It is not an automaton (it cannot move), not a robot (it cannot act), and not an android (its human resemblance is purely cosmetic). It stands as a unique example of Indian jugaad—an imaginative solution powered more by software aspiration than robotic hardware.

A Mirror to Ourselves

The story, however, transcends technicalities. The episode recalls V.S. Naipaul's 'An Area of Darkness', a book once banned for its critical portrayal. The reaction to Sophie revealed a different kind of darkness: a reflexive, almost algorithmic cynicism in public discourse. While Sophie merely responded to inputs, the mockery it faced was strikingly uniform—identical jokes and sneers replicated across the digital landscape.

This prompts a philosophical counter-question: In an age driven by social media algorithms and cultural conditioning, how different are we from programmed systems? Isaac Asimov's famed Three Laws of Robotics were designed to ensure machines act with restraint and care for humanity. Observing the knee-jerk dismissal of a young innovator's attempt, it's worth asking if we hold ourselves to a similar standard of thoughtful response.

The real narrative here isn't about a machine's limitations, but about human potential and reaction. The light in this story comes from a boy in Bulandshahr who dared to build. The shadow comes from those who, perhaps performing more robotically than they realise, rushed to dismantle rather than understand. The debate over Sophie's identity ultimately holds up a mirror, asking us to define not just machines, but the quality of our own curiosity and engagement.