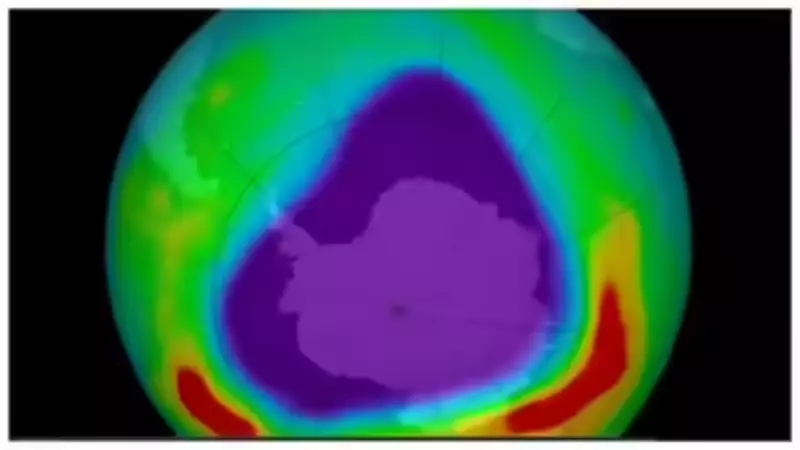

In a significant environmental breakthrough, scientists from NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have reported encouraging signs of recovery in Antarctica's ozone layer. This year's ozone hole has demonstrated steady improvement, ranking as the fifth smallest since 1992 and showing early breakup patterns that signal the positive impact of global environmental agreements.

Record-Breaking Recovery Patterns

Early observations reveal that the ozone hole is breaking up nearly three weeks earlier than in previous years, marking a substantial improvement in the atmospheric phenomenon. During the peak ozone depletion season from September 7 to October 13, the average size of the hole measured approximately 7.23 million square miles (18.71 million square kilometers).

The ozone hole reached its maximum single-day size on September 9 at 8.83 million square miles (22.86 million square kilometers). This measurement represents a remarkable 30% reduction compared to the largest ozone hole ever recorded in 2006, which spanned 10.27 million square miles (26.60 million square kilometers). Based on satellite records dating back to 1979, this year's ozone hole ranks as the 14th smallest over 46 years of continuous monitoring.

Scientific Community Celebrates Progress

Paul Newman, a senior scientist at the University of Maryland system and longtime leader of NASA's ozone research team, expressed optimism about the trends. "As predicted, we're seeing ozone holes trending smaller in area than they were in the early 2000s," Newman stated. "They're forming later in the season and breaking up earlier."

Stephen Montzka, senior scientist with NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory, provided crucial data supporting the recovery. "Since peaking around the year 2000, levels of ozone depleting substances in the Antarctic stratosphere have declined by about a third relative to pre-ozone-hole levels," he confirmed through NOAA's official statement.

Newman emphasized the dramatic impact of these changes, noting that "This year's hole would have been more than one million square miles larger if there was still as much chlorine in the stratosphere as there was 25 years ago."

Multiple Factors Driving Improvement

Weather balloon data collected this year showed that the ozone layer directly over the South Pole reached its lowest concentration of 147 Dobson Units on October 6. While this indicates ongoing depletion, it represents significant improvement from the record low of 92 Dobson Units recorded in October 2006.

Laura Ciasto, a meteorologist with NOAA's Climate Prediction Center and ozone research team member, explained that natural factors also contributed to this year's positive results. "A weaker-than-normal polar vortex this past August helped keep temperatures above average and likely contributed to a smaller ozone hole," she noted, highlighting how weather patterns, temperature variations, and vortex strength all influence ozone levels.

The Montreal Protocol's Lasting Impact

Scientists from both NASA and NOAA confirm that international controls on ozone-depleting chemicals established under the Montreal Protocol and its subsequent amendments are directly responsible for the gradual recovery of the ozone layer. This landmark international treaty, adopted in 1987, successfully phased out numerous harmful substances including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other ozone-depleting chemicals.

Earth's ozone layer, located in the stratosphere between 7 and 31 miles above the surface, serves as a crucial protective shield against harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Reduced ozone levels allow more UV rays to reach the Earth's surface, increasing risks of skin cancer, cataracts, and crop damage.

Ozone depletion occurs when chlorine- and bromine-containing compounds reach the stratosphere and react with ozone molecules. Although these substances are now banned, they persist in older products like building insulation and landfills, gradually decreasing over time. Based on current recovery rates, scientists project that the Antarctic ozone hole could fully recover by the late 2060s, marking a major environmental success story for global cooperation.