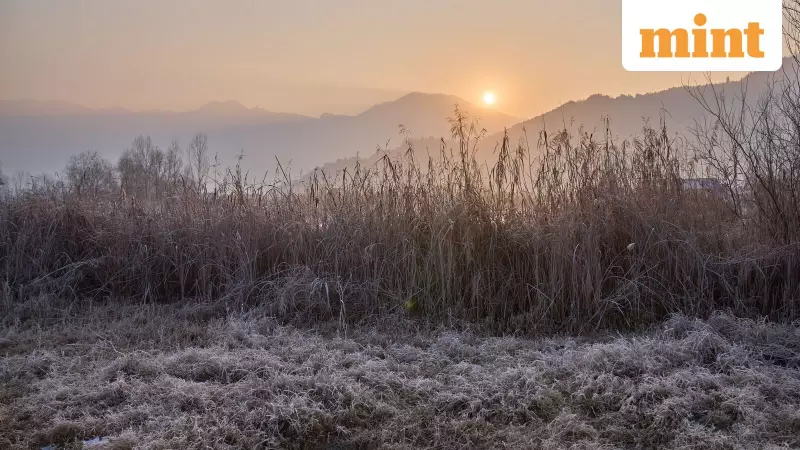

Kashmir finds itself in the grip of a strange winter. The sun rises over frost-covered fields near Dal Lake in Srinagar, but the ground remains bare. Temperatures drop sharply at night, yet the snow that once defined this season refuses to fall. This marks the third consecutive winter with inadequate snowfall, leaving residents caught between worry and disbelief.

The Missing Snowfall

During Chilai Kalan, the traditional 40-day harsh winter period from late December through January, Kashmir typically experiences its coldest months. This year, like the previous two, the Valley waits for snow that never arrives. Last winter brought only brief spells of snow, none lasting long enough to accumulate. Across much of the Himalayan region, cold but snowless winters are becoming increasingly common, disrupting communities accustomed to predictable seasonal rhythms.

In Srinagar's downtown area, known locally as Shahar-e-Khaas, elderly men gather outside shopfronts, sharing memories of winters past. "When I was a child, December and January were thick with snow," said Ghulam Mohammad Tibet Baqal, a 66-year-old resident of Lal Bazar. "One or two feet would stay frozen until the last week of February. Now those blessings have vanished."

Scientific Explanations

Scientists point to global warming as the primary cause of Kashmir's snow drought. The Valley has warmed by approximately 0.8°C since the 1980s, with the pace accelerating after 2000. An earlier warning came in 2007 when ActionAid reported average temperatures in the region had already risen by 1.45°C.

Recent data confirms the trend. The Indian Meteorological Department revealed December 2025 passed with almost no rain or snow across large parts of northern India. The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development reported the 2024-25 winter recorded nearly 24% below-normal snow persistence, the lowest level in 23 years.

Elevation-Dependent Warming

Climate scientists explain that mountain regions like the Himalayas respond more sharply to warming than lowland areas, a phenomenon called elevation-dependent warming. Even small temperature increases can push winter precipitation past the freezing threshold, turning snow into rain and shortening snowpack duration.

In Kashmir, effects are most evident in the upper Jhelum basin, where snow melts weeks earlier in high-altitude zones between 3,000 and 6,000 meters. These areas feed glaciers, springs, and tributaries like the Lidder and Sind rivers. Earlier snowmelt creates erratic runoff patterns, reducing base flows during dry months while increasing flood risks during intense rainfall.

The Emissions Paradox

A persistent question echoes across the Valley: why is snow disappearing in a region with minimal industry? Data from Greenhouse Gases Platform India reveals Jammu and Kashmir actually absorbs more greenhouse gases than it emits. In 2018, the region removed about 16.36 million tonnes more carbon dioxide equivalent than it released, largely due to carbon-absorbing forests and land use.

Per capita figures reinforce this picture. Jammu and Kashmir recorded net per capita emissions of minus 1.25 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2018, compared to India's national average of 2.24 tonnes. Industry accounts for only about 2% of gross emissions, mostly from small cement operations rather than heavy manufacturing.

Global Winds, Local Consequences

Shakil Ahmad Romshoo, vice chancellor of the Islamic University of Science and Technology, explains the disconnect. "Kashmir is not causing climate change, but it is bearing the maximum brunt of it. Our winds come from the Atlantic, passing over Europe and other industrialized regions before reaching the Himalayas. Along this long journey, they carry pollutants. What happens far beyond our borders directly affects our climate."

Mutaharra A. W. Deva, a Srinagar-based policy consultant and climate change expert, adds perspective. "Greenhouse gases do not respect borders. Carbon dioxide, methane and other heat-trapping gases released thousands of kilometers away mix uniformly in the atmosphere. Once global temperatures rise, every climate-sensitive region responds, regardless of local emissions."

Daily Life Impacts

The consequences of vanishing snow are already reshaping daily decisions across Kashmir. Snowfall traditionally sustained livelihoods tied to water, tourism, and agriculture. Its disappearance creates new challenges.

"Water shortages are forcing some families to leave their villages," Baqal explained. "Land is losing value, and in a few places even marriages are being shaped by scarcity. Families become reluctant to settle daughters in communities where water has become uncertain."

Weather Pattern Shifts

Weather experts emphasize that Kashmir's winters cannot be understood through purely local lenses. Faizan Arif, an independent weather forecaster and climate analyst, notes snowfall in Kashmir is driven by western disturbances originating over the Mediterranean and traveling thousands of kilometers before reaching the Himalayas.

"What Kashmir is witnessing now—persistently weaker winter precipitation and declining snowfall—is not a short-term anomaly," Arif said. Rising global temperatures reshape jet streams that steer Western Disturbances, making them fewer, weaker, or warmer. "That increasingly means rain instead of snow, or snowfall that is brief and ineffective."

Sonam Lotus, former director of the Srinagar weather office, observes snowfall has thinned even in higher reaches like Gulmarg, Sonamarg, and Pahalgam. This January, Jammu was colder than Gulmarg—an inversion once considered implausible. "Snow now often arrives late, slipping into February rather than settling in December," Lotus noted.

Local Contributing Factors

While global factors dominate, scientists also point to local elements that can intensify warming. Dr. Riyaz Ahmad Mir of the National Institute of Hydrology explains climate change operates at both global and local scales. Black carbon from vehicles, biomass burning, and winter heating settles on snow and glaciers, darkening surfaces and accelerating melt.

Environmental activist Raja Muzaffar Bhat acknowledges growing local pressures. "Leave global factors aside for a moment, local factors are equally responsible." He points to deteriorating air quality as a visible marker of stress, citing Central Pollution Control Board data showing Srinagar's air quality falling into the 'poor' category last autumn.

Industrial Perspective

Industry representatives argue Kashmir's industrial footprint remains tightly controlled. Sarwar Malik, general secretary of the Industrial Association at Lassipora, Kashmir's largest industrial estate, notes nearly 98% of industrial units are small and micro enterprises operating under strict environmental norms.

"Industries in Kashmir can only be set up in government-designated zones," Malik explained. "Before operations begin, units must obtain mandatory clearances from the Pollution Control Board and SIDCO. Without pollution clearance, no industry can legally function here."

A Climate Hotspot

Deva describes Kashmir as sitting at the intersection of multiple vulnerabilities. "High-altitude cryosphere, dependence on snowfall, sensitive ecosystems and small temperature margins. That is why Kashmir has effectively become a climate change hotspot."

Snow loss here represents not a local failure but a symptom of an uneven global climate system where warming costs are often borne far from emission sources. Romshoo warns that if current trends continue, Kashmir's people may one day need to travel outside the Valley to experience snowfall—an extraordinary reversal for a place once defined by its winters.