The Supreme Court of India has put a crucial judgment on hold, spotlighting the critical need for scientific expertise in environmental governance. The court stayed its own November 20 order that had adopted a controversial definition for the ecologically fragile Aravali hills based on a 100-meter height cutoff. This decision has thrown the composition of the Union Environment Ministry's (MoEF) technical committee, which proposed the definition, into sharp scrutiny.

Questioning the Bureaucrat-Heavy Panel

The bench, led by Chief Justice Suryakant alongside Justices JK Maheshwari and AG Masih, has now proposed to constitute a new committee of domain experts. This panel will undertake an "exhaustive, holistic and scientific" examination of the Aravali hills and ranges. The aim is to draft a comprehensive definition that protects the region's "structural and ecological" integrity.

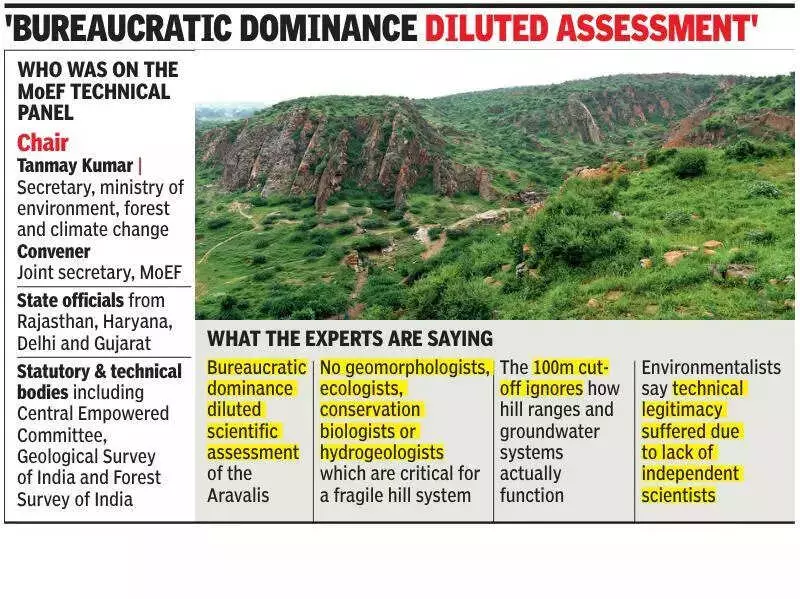

The move comes after it was revealed that the original nine-member MoEF technical committee was dominated by bureaucrats. Six of its nine members were administrative officials, including its chair and MoEF Secretary Tanmay Kumar, the MoEF joint secretary, and the forest secretaries of the four Aravali states: Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat. The remaining three members were representatives from the Supreme Court's Central Empowered Committee (CEC), the Forest Survey of India (FSI), and the Geological Survey of India (GSI).

Immediate Ban on Mining and Judicial Oversight Restored

In a significant interim order, the Supreme Court bench has imposed an immediate ban on all mining activities in the Aravali region. "Until further orders, no permission shall be granted for mining, whether it is for new mining leases or renewal of old mining leases, in the Aravali hills and ranges... without prior permission of this court," the bench stated. The court defined the area based on the Forest Survey of India Report of August 25, 2010.

The bench has issued notices to the Centre and the governments of Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat, seeking their responses within four weeks. The next hearing is scheduled for January 21. Legal experts view this stay order as a restoration of judicial oversight over a process that had, in their opinion, drifted away from science-based assessment.

Experts Decry "Arbitrary" Definition and Flawed Process

Environmental and legal experts have welcomed the Supreme Court's intervention, highlighting the core flaws in the earlier definition. The proposed definition, intended for mining regulation, suggested recognizing only landforms rising 100 meters or more from the lowest enclosing contour as an Aravali hill, with nearby hills within 500m grouped as a range.

Debadityo Sinha, lead for climate and ecosystems at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, called the 100m rule "arbitrary." He argued that the key question was never about average elevation but the ecological role of thousands of low-relief hills in groundwater recharge and biodiversity. "Committees without independent ecologists relied on bad statistics," he stated, advocating for a reconsideration based on science and constitutional principles.

Echoing this, retired Haryana forest conservator MD Sinha called the earlier process "a case of technical evaluation being overshadowed by administrative control." He noted that the environment ministry was seen as behaving like a mining ministry, with secretaries making calls that should have been left to domain experts.

RP Balwan, another retired Haryana forest conservator whose petition was admitted by the Supreme Court, warned that any definition based on vertical limits in the inconsistent Aravali ecosystem "is bound to destroy the entire system beyond repair." He asserted that the Aravalis are already well-defined in geological terms and need no new, restrictive definition.

Forest analyst Chetan Agarwal welcomed the stay, stating that focus must now shift to the new high-powered committee's constitution and mandate. He expressed hope that the new panel would view the Aravalis as a living ecological entity crucial for forest cover, air pollution moderation, and groundwater recharge.

Incidentally, the MoEF's own affidavit had noted that height and slope were insufficient parameters for defining the Aravalis, warning that a sole criterion would lead to "inclusion and exclusion error" due to the terrain's considerable variation. The Supreme Court's latest order underscores the imperative to prioritize ecological science over administrative convenience in safeguarding India's critical natural barriers.