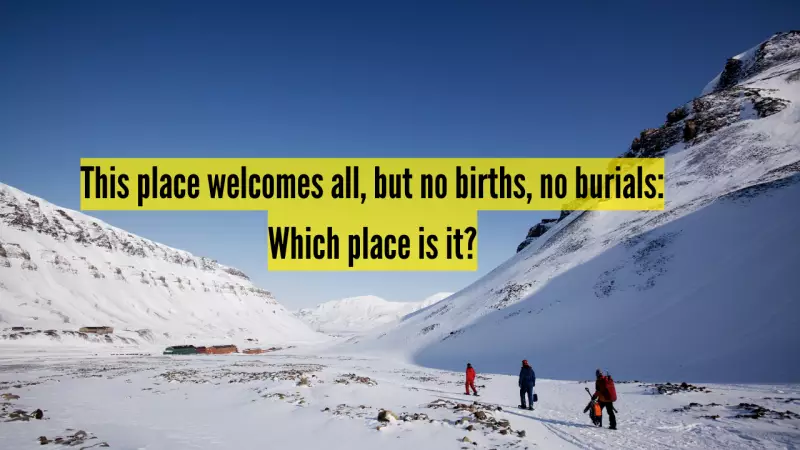

Far above the Arctic Circle, winter swallows daylight for months. In this remote region lies an extraordinary place that quietly challenges our ideas about permanent settlement. This place is Svalbard, a Norwegian-governed Arctic archipelago shaped by an international treaty. It is not designed for people to stay forever. Instead, it welcomes those who come, live for a while, and then leave.

The Reality Behind the Myths

People often call Svalbard "Depression Island" because of its long, sunless winters. Persistent myths surround this place. Many believe it is illegal to die or give birth there. The truth is more subtle and far more revealing about human adaptation at the edge of the habitable world.

Svalbard does not function like a conventional town or city. The archipelago lacks long-term hospital facilities and a standard burial system. Pregnant women must travel to mainland Norway, typically to Tromsø, several weeks before their due date. Similarly, when someone dies, their body is transported south for burial.

Practical Responses to Extreme Conditions

These practices are not symbolic bans on birth or death. They are pragmatic responses to the Arctic environment. Permafrost makes burial environmentally risky. Maintaining advanced medical infrastructure for a small, shifting population is neither practical nor safe.

Svalbard is intended for residents who are healthy, mobile, and self-sufficient. The archipelago makes its expectations clear through these restrictions.

Life in Longyearbyen

Most of Svalbard's population lives in Longyearbyen, the largest settlement. Including nearby research hubs like Ny-Ålesund, around 2,500 people live on the islands. They represent roughly 50 nationalities, with Norwegians forming the largest group.

This diversity reflects Svalbard's unusual legal status. Under the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, citizens of signatory countries can live and work there without a visa. Consequently, the population remains transient, shaped by research assignments, tourism seasons, mining, and short-term contracts.

Daily Life and Traditions

Dogs are deeply woven into life on Svalbard. The islands maintain an estimated 1,200 dogs—nearly one for every two people. This strong sled-dog tradition continues with many dogs living in kennels outside town, still used for transport and tourism.

Increasingly, retired sled dogs find new homes through adoption. They trade long Arctic runs for quieter companionship with local families.

Daily life unfolds under extreme conditions. In winter, darkness dominates completely. In summer, the sun never sets. These cycles shape work schedules, mental health, and social life in ways that mainland societies rarely experience.

Understanding the Restrictions

No one is denied medical care or emergency assistance in Svalbard. If a baby is born unexpectedly, local facilities can handle emergencies, including premature births. Likewise, death is not prohibited.

What Svalbard does restrict is long-term dependency. There is no extensive social safety net for residents who develop serious illnesses or require ongoing care. The archipelago expects residents to manage its extremes independently.

A Carefully Managed Experiment

Svalbard is not a frozen oddity where rules defy humanity. It represents a carefully managed experiment in living lightly within one of the world's most fragile environments. Its policies reflect limits of geography, climate, and sustainability—rather than cruelty or control.

Life here is temporary by design. Perhaps that is what makes Svalbard so compelling. It reminds us that not every place is meant to hold us forever. This Arctic archipelago shows how human communities can adapt to extreme conditions through practical, sustainable policies.