The Wallace Line: Nature's Invisible Barrier That Divided Continents

Have you ever examined a world map and pondered why tigers prowl certain Indonesian islands while kangaroos inhabit neighboring lands, with the two never encountering each other? This fascinating separation represents one of nature's most distinct neighborhood boundaries, where wildlife remains segregated despite minimal geographical distances. This biological divide has intrigued scientists for generations, presenting a puzzle that has only recently been unraveled through advanced scientific investigation.

The Discovery That Changed Biogeography Forever

Exactly 160 years ago, pioneering naturalist and explorer Alfred Russel Wallace first identified this peculiar biological boundary during his extensive travels through the Malay Archipelago. Between 1854 and 1862, Wallace embarked on an extraordinary eight-year expedition covering approximately 14,000 miles while collecting an astonishing 125,660 specimens, including thousands of previously undocumented insects, birds, and mammals for Western science.

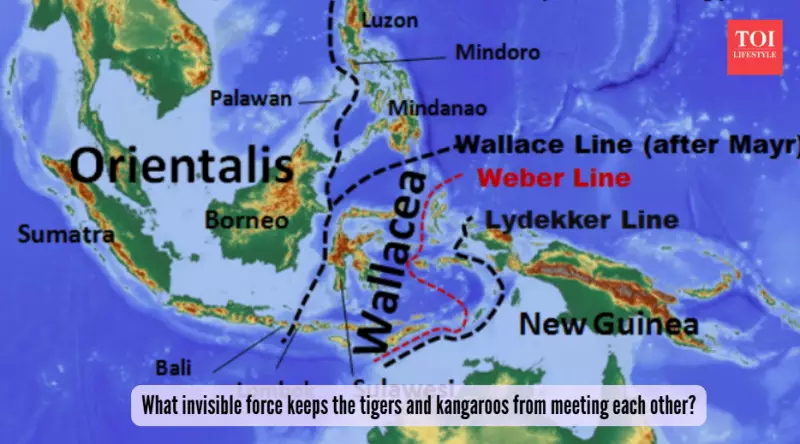

His breakthrough moment occurred in 1856 when he crossed the narrow strait separating Bali from Lombok. On Bali, he documented distinctly Asian bird species including barbets and woodpeckers. Upon reaching Lombok, however, the biological landscape transformed dramatically, revealing Australian cockatoos and megapodes as the dominant species. This sharp biological demarcation inspired what would become known as the Wallace Line, effectively carving Indonesia into distinct Asian and Australian biological zones.

Tectonic Collisions and Climate Shifts: The Real Bouncers of Evolution

The story begins approximately 50 million years ago when Australia separated from Antarctica and began its northward drift, eventually colliding with Asia's southeastern edge. This monumental tectonic convergence created Indonesia's volcanic islands while establishing deep ocean trenches that would serve as formidable barriers to most terrestrial animals.

Around 35 million years ago, another critical development occurred with the opening of the Drake Passage, which initiated the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. This oceanic shift triggered global cooling that transformed Antarctica into an icy continent while replacing the warm Eocene climate with the drier Oligocene conditions. These environmental changes created challenging new habitats that would test which species could successfully navigate the humid island chains between Sunda (Asian) and Sahul (Australian) landmasses.

Modern Science Cracks the 160-Year-Old Mystery

A groundbreaking 2023 collaborative study between Australian National University and ETH Zurich researchers has finally provided definitive answers using sophisticated climate modeling technology. The team employed Gen3SIS models to analyze approximately 20,000 vertebrate species across 30 million years of evolutionary history.

The research revealed a surprising pattern: Asian species, already adapted to humid tropical environments, successfully spread eastward into Australia. Meanwhile, Australian animals that had evolved during their continent's long period of isolated, arid conditions struggled to survive in Wallacea's steamy forests—the Indonesian islands that serve as biological transition zones.

"Asian fauna were already well-adapted to tropical conditions, which gave them a significant advantage when colonizing Australia," explained lead researcher Dr. Alex Skeels. The study found that dispersal rates from Asia to Australia were approximately twice as high as movement in the opposite direction, effectively creating a biological one-way street.

Why Marsupials Couldn't Make the Return Journey

The research identified several key factors that prevented Australian marsupials from crossing westward. Smaller Asian mammals like shrews and rodents could island-hop relatively easily, but larger Australian species such as kangaroos and koalas faced insurmountable barriers.

"If you travel to Borneo, you won't see any marsupial mammals, but head to neighboring Sulawesi and you will," Skeels noted, highlighting the precise nature of this biological boundary. The humid tropical conditions favored Asian species accustomed to such environments, while Australia's dry-climate specialists found Wallacea's steamy forests inhospitable.

Additional geographical obstacles including deep ocean trenches and volcanic island chains further restricted movement, transforming potential biological bridges into permanent barriers. This combination of climatic preferences and geographical constraints created the enduring Wallace Line that continues to define Asian and Australian fauna distribution today.

Lessons for Our Warming World

This research extends far beyond historical curiosity, offering crucial insights for understanding how climate change might redraw biological boundaries in our rapidly warming world. The study demonstrates how relatively minor climatic shifts can dramatically alter species distribution patterns, potentially creating new biological divides or eliminating existing ones.

The Wallace Line serves as a powerful reminder that Earth's biological map remains dynamic, with climate acting as a primary architect of species distribution. As global temperatures continue to rise, similar biological boundaries may emerge or disappear, reshaping ecosystems in ways that scientists are only beginning to comprehend.

Wallace's 160-year-old observation has thus evolved from a geographical curiosity into a vital case study for understanding how climate, geology, and evolution interact to create the biological world we inhabit today—and how that world might transform tomorrow.