The Winter Phenomenon: Understanding Frost Cracking in Trees

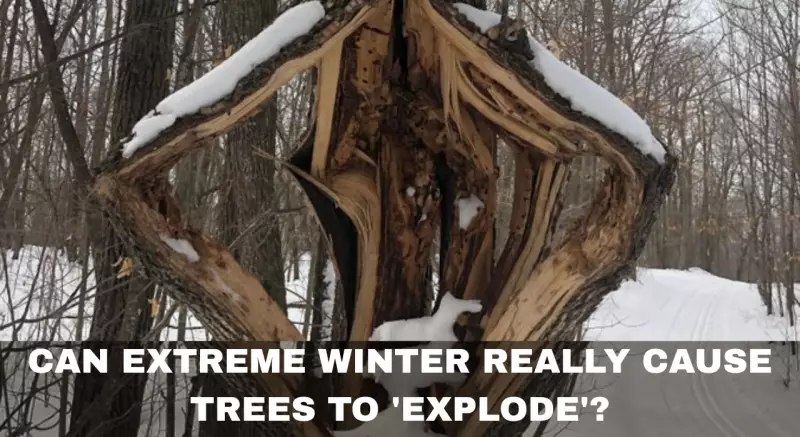

Across various parts of the world, winter has firmly established its presence with intense conditions. Sub-zero temperatures, sudden freezes, and heavy snowfall are impacting numerous regions, bringing with them an unexpected auditory side effect: sharp, echoing cracking sounds resonating through parks, streets, and back gardens. Online, dramatic videos capturing these noises, ranging in intensity, have rapidly spread, often accompanied by sensational warnings that trees are "exploding" due to the cold. However, forestry experts clarify that this portrayal is misleading. While trees are indeed reacting to the harsh weather, the sounds are attributed to a well-documented phenomenon known as frost cracking, which is dramatic, sometimes startling, but widely misunderstood.

The Science Behind the Sounds

John Seiler, a professor and tree physiology specialist at Virginia Tech, emphasized to CNN that while winter weather can certainly damage trees, the viral framing has outpaced scientific understanding. "They're not actually exploding, at least not in the way the phrase suggests," he stated. When temperatures plummet suddenly, trees often lack sufficient time to acclimatize. Water and sap within their tissues begin to freeze, and as freezing water expands, it creates internal stress. This effect is particularly pronounced when the outer layers of the tree cool faster than the inner wood.

Doug Aubrey, a professor at the University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, explained, "That water expands as it freezes, and it can happen usually under very, very drastic drops in temperature." The situation is exacerbated by uneven contraction. According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, rapid temperature declines can cause the bark to shrink faster than the interior wood, leading to what the agency terms "unequal contraction" between a tree's outer and inner tissues.

Bill McNee, a forest health specialist with the Wisconsin DNR, likened the process to ice expanding in a freezer. "When it does that, like ice cubes in your freezer, it expands very quickly," he noted. The resulting physical pressure, he elaborated, can cause the wood to split, producing the loud cracks audible to people and occasionally leading to branches shedding.

Loud, Dramatic, and Typically Harmless

The sound of frost cracking can be jarring, often resembling a gunshot or sudden bang in the quiet of winter. While proximity during such events is not advisable, documented effects are generally limited to frost cracks and falling branches. Truly dramatic occurrences, such as trees "exploding" as depicted in some viral videos, remain extremely rare. Experts caution that some clips may even be AI-generated or staged for views, advising viewers to approach them with skepticism.

Most frost cracks are harmless, as emphasized by specialists. "While frost cracks can be loud and cause branches to fall off, it would be extremely rare for a tree to fully explode because of it," McNee affirmed. More commonly, the split integrates into the tree's structure over time. Simon Peacock, an ISA-certified arborist with Green Drop Tree Care in Winnipeg, told CBC Canada that these cracks typically close once temperatures rise. "The break doesn't harm the tree and will heal when the temperature warms up in the summer," he said, though he noted that the same crack might reopen in subsequent winters. Serious damage cases are unusual, and it is "extremely rare" to witness the destruction shown in some social media posts. Many people may never notice a frost crack unless they happen to hear it. "It's going to be loud, but it's not dangerous," Peacock reassured. "Wood doesn't go flying through the area." For the tree itself, the split is not fatal, although damaged bark can potentially allow insects, fungi, or bacteria to enter.

Which Trees Are Most Vulnerable?

Frost cracks tend to develop along existing weak points in a tree's bark. Eric Otto, a forest health specialist at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, explained to The New York Times, "These cracks tend to happen at a previous weak spot in the bark." Thin-barked species, such as maples, lindens, and birches, are more susceptible, though frost cracking can occur across various tree types. Trees not native to a region may face higher risks if they are unadapted to extreme cold. "Native trees can get frost cracks, but nonnative trees can be more susceptible if they are not adapted to the area," Otto noted. "I suspect that in areas that don't typically have below-zero temperatures, those trees would also be more prone to frost cracks."

Why Most Trees Survive Winter Intact

Trees are not passive during winter; many shed much of their internal water before cold sets in, entering a dehydrated, dormant state that enhances their ability to withstand freezing conditions. Their internal structure also provides redundancy. "A tree has thousands of vessels, or pipes," Otto elaborated, "so if one bursts, the tree can continue to function." Only in extreme cases, typically involving severe and rapid temperature swings, do frost cracks fail to heal and significantly compromise a tree's health.

As winter deepens, experts assure that these unsettling noises are not indicators of catastrophe. They are simply the sound of living material responding to cold—dramatic, brief, and, in most instances, nothing to fear.