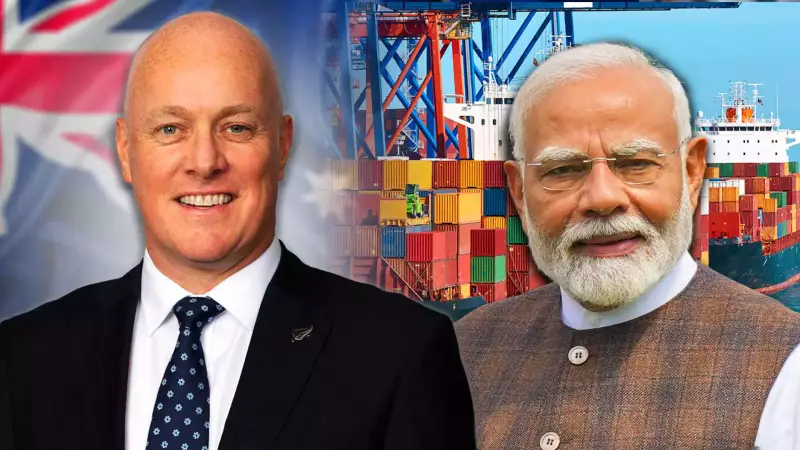

New Zealand's proposed free trade agreement (FTA) with India, hailed as a landmark deal by Prime Minister Christopher Luxon, has immediately run into political turbulence within the country's ruling coalition. The pact, which aims to secure New Zealand's position in India's massive future economy, is facing outright rejection from the government's partner, the NZ First party.

Coalition Rift Over Dairy and Immigration

The core of the disagreement lies in two sensitive areas: dairy market access and immigration rules. While the Luxon-led government asserts the agreement delivers significant benefits for sectors like agriculture, forestry, seafood, and services, NZ First has dismissed it as a bad deal for New Zealand. The party's opposition suggests the concessions made, potentially in dairy, are too great, and it may also be concerned about immigration provisions linked to the pact.

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon is vigorously defending the agreement. He argues that the FTA is crucial to prevent New Zealand exporters from losing ground to competitors like Australia, which already has a trade deal with India. Luxon emphasizes the strategic importance of positioning New Zealand inside India's $12 trillion future economy, viewing the agreement as a historic opportunity for long-term growth.

The Legislative Battle Ahead

With the agreement yet to be formally signed and the necessary legislation still to be passed in parliament, its fate is now uncertain. The government requires broad support to enact the deal into law. The public rejection by NZ First, a key coalition partner, has exposed significant cracks in the ruling alliance.

The future of the New Zealand-India FTA now hinges on whether Prime Minister Luxon can muster enough bipartisan support from opposition parties to overcome the resistance from within his own coalition. This internal conflict sets the stage for a challenging political debate in New Zealand, with a major trade relationship with India hanging in the balance.

What This Means for the Deal

The timing of this rift, emerging even before the deal's official signing, is a major setback for the government's trade agenda. It highlights the difficulties of negotiating comprehensive agreements that satisfy diverse political interests. The stalemate means:

- Delay or renegotiation: The process could be delayed, or parts of the deal may need to be revisited to placate NZ First.

- Reliance on opposition: The government may be forced to seek votes from the Labour opposition, a politically tricky maneuver.

- Uncertainty for businesses: Exporters and industries anticipating gains from the FTA are left in a state of limbo.

The coming weeks will be critical in determining if this promised historic partnership with India can survive New Zealand's domestic politics.