Every year on December 22, India celebrates National Mathematics Day to honour the legacy of Srinivasa Ramanujan, a man whose mind seemed to grasp the infinite. While popular narratives often paint him as an inscrutable genius, a closer look at a single number—1729, known as the Hardy–Ramanujan number—reveals a more profound truth about his work ethic and intellectual rigour.

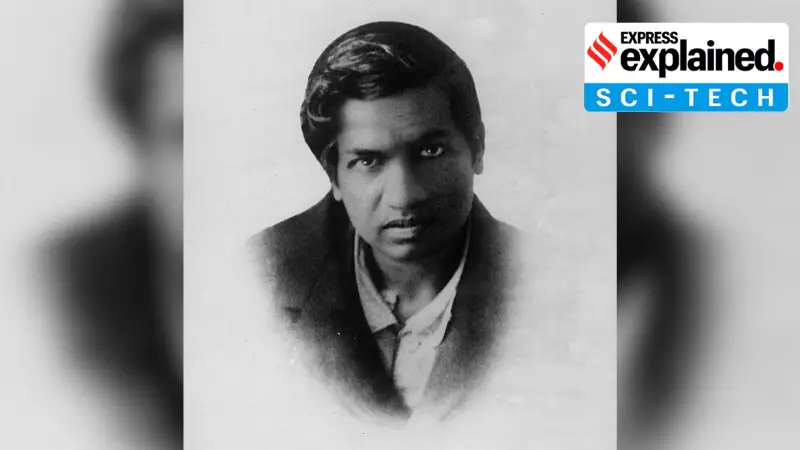

The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Brief Portrait

Srinivasa Ramanujan was born in 1887 into a Tamil Brahmin Iyengar family in Erode, and grew up in the temple town of Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu. Despite dying at the young age of 32 due to ill health, his contributions to mathematics were monumental. He became one of the youngest Fellows of the Royal Society and the first Indian to be elected a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge.

His journey to recognition began in 1913 when he wrote letters to the renowned British mathematician G. H. Hardy. Hardy, recognising the extraordinary talent in the self-taught Indian, invited him to England. However, Ramanujan's time there was marred by poor health, exacerbated by the cold climate and difficulties in maintaining a nutritious vegetarian diet, leading to frequent hospitalisations.

The Tale of a "Dull" Taxicab Number: 1729

The story of the Hardy–Ramanujan number originates from one such hospital visit in Putney. Hardy arrived in a taxi numbered 1729 and remarked to Ramanujan that the number seemed rather dull and uninteresting. Ramanujan's instantaneous reply has become legendary: "No, Hardy, it is a very interesting number; it is the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways."

He was referring to the unique property:

1³ + 12³ = 1 + 1728 = 1729

and

9³ + 10³ = 729 + 1000 = 1729.

This immediate insight into a seemingly random number is often cited as the ultimate proof of his intuitive genius. It appeared as if patterns and connections revealed themselves to him magically, a notion reinforced by his own accounts of visions from the family deity, Goddess Namagiri.

Beyond Intuition: The Rigorous Mind Behind the Magic

However, the story of 1729 reveals more than just flashy intuition. It underscores a lifetime of deep, unconventional study. Mathematicians like Ken Ono and Amir D. Aczel, in their book "My Search for Ramanujan: How I Learned to Count", point out that Ramanujan's recognition was not a random divination.

He was already deeply familiar with the properties of 1729 because of his prior work on problems studied by the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler. Furthermore, the number appears in Ramanujan's exploration of Fermat's Last Theorem—Pierre de Fermat's famous assertion that no two cubes can add up to another cube.

Ramanujan was fascinated by "near misses" to this theorem. For instance, if 9³ + 10³ had equaled 1728 (which is 12³), it would have violated Fermat's centuries-old claim. The fact that it equaled 1729, just one unit away, was a tantalising near-violation that captivated his analytical mind. His instant recall in the hospital was, therefore, the result of a preoccupied and deeply studied fascination with numerical rules and patterns.

Conclusion: Demystifying the Genius

The Hardy–Ramanujan number serves as a perfect metaphor for the mathematician himself. On the surface, it speaks to an almost supernatural ability to see patterns. But digging deeper, it reveals the rigorous, innovative, and relentless thinker who trained his mind through obsessive study. Ramanujan was not merely "unusually blessed"; he was a dedicated scholar whose notebooks were filled with the evidence of his labour.

On his 138th birth anniversary, the number 1729 reminds us that true genius often lies at the intersection of innate talent and disciplined work. Celebrating Srinivasa Ramanujan means looking beyond the myth of the dream-inspired sage to understand the profound and methodical intellect that continues to inspire mathematicians and non-mathematicians alike.