Greek filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos continues to push cinematic boundaries with his latest film Bugonia, starring Jesse Plemons and Emma Stone. This new release reinforces his position as the leading voice of the Greek Weird Wave, an extraordinary film movement that emerged from Greece's financial turmoil in the late 2000s.

The Unconventional World of Bugonia

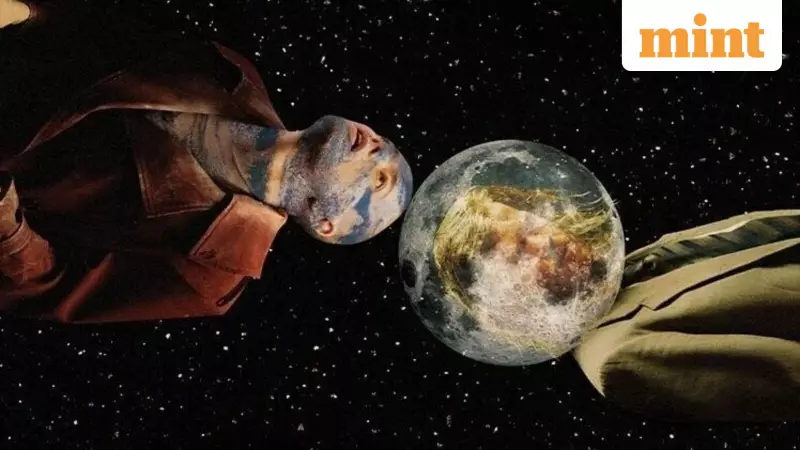

In Bugonia, Jesse Plemons delivers a compelling performance as Teddy, a grimy conspiracy theorist and beekeeper who becomes convinced that pharmaceutical CEO Michelle Fuller, played by Emma Stone, is an alien plotting humanity's destruction. The film's premise bears resemblance to Martin Scorsese's The King of Comedy, where a delusional individual kidnaps a celebrity, creating a narrative that keeps audiences constantly guessing about the story's direction.

What makes Lanthimos's work distinctive is his fearless approach to storytelling. He constructs intricate plots around expansive, fantastical concepts while maintaining a unique visual and narrative style. This characteristic uncertainty about where the story will ultimately lead has become a hallmark of his filmmaking, with each destination proving stranger and darker than viewers might anticipate.

The Greek Weird Wave Movement

The Greek Weird Wave represents a significant departure from traditional Mediterranean cinema. Born during Greece's severe economic collapse and social unrest, this movement rejected conventional storytelling and visual exuberance in favor of deadpan absurdism and gritty explorations of contemporary issues.

Lanthimos stands at the forefront of this movement, but he's joined by other notable filmmakers including Athina Rachel Tsangari, Panos H. Koutras, Yannis Economides, and Argyris Papadimitropoulos. These directors have created a body of work that examines sex, gender, politics, and family through unconventional lenses.

Tsangari's Chevalier presents a savage satire of toxic masculinity aboard a boat where six men engage in competitive measuring contests with ambiguous stakes. Meanwhile, Babis Makridis's Pity explores how grieving individuals can become addicted to receiving sympathy. These films don't claim to provide solutions to Greece's complex problems but instead offer unsettling, unorthodox perspectives on contemporary life.

Lanthimos's Cinematic Evolution

Lanthimos first gained international recognition with Dogtooth in 2009, a disturbing examination of manipulative parenting that earned an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. The film follows parents who keep their children completely isolated from the outside world, creating an unnervingly original narrative that established Lanthimos's distinctive style.

His 2015 English-language breakthrough The Lobster presented a ridiculous dystopian premise where single people have 45 days to find partners or be transformed into animals. The film finds humor in uncomfortable situations, particularly breakfast scenes where newly coupled individuals taunt desperate singles, creating what amounts to motivational torture.

With The Favourite in 2018, Lanthimos adopted a more playful yet equally acidic tone. This period satire exploring femininity and power in Queen Anne's court utilized fisheye and wide-angle lenses that transformed palatial rooms into both playgrounds and prisons.

His 2023 masterpiece Poor Things arrived as a cinematic revelation. Featuring steampunk aesthetics, retro-futuristic technology, lavish sets, and Emma Stone's tour de force performance as Bella Baxter—a woman reanimated with an infant's brain—the film made conventional Frankenstein adaptations appear tired and timid by comparison.

The Lanthimos-Stone Collaboration

Emma Stone has emerged as Lanthimos's most significant collaborator, a performer equally fearless in her approach to challenging roles. Their partnership began with The Favourite, where Stone played the ambitious and conniving Abigail. This collaboration continued through the surreal black-and-white short Bleat, then Poor Things, where Stone remarkably depicted Bella's psychological and psychosexual development.

Their creative partnership has extended to Kinds of Kindness and now Bugonia, where Stone portrays a steely Big Pharma executive confronting passionate adversaries. Stone's willingness to surrender vanity, to appear physically ungainly and morally compromised, makes her the ideal vessel for Lanthimos's vision—a performer who treats transformation not as risk but as liberation.

Throughout Lanthimos's work, there exists an extraordinary beauty and melancholy that often hides beneath the surface absurdity. In Poor Things, Bella's journey from reanimated curiosity to self-actualized woman carries bittersweet weight as she witnesses socioeconomic inequality, grapples with philosophical pessimism, and rejects assigned rules and cynicism. Her attempts to create change don't always succeed, and these beautiful, human failures become where the melancholy resides.

This emotional complexity explains why Lanthimos uses Marlene Dietrich's Where Have All the Flowers Gone? at the conclusion of Bugonia. The director consistently finds humor in uncomfortable situations while using comedy to mock detestable characters, as seen in Poor Things where Duncan's "furious jumping" with the mentally underaged Bella becomes a condemnation of patriarchal possession.

Lanthimos represents a rare filmmaker who refuses to repeat himself, treating each project as an opportunity to reinvent not just his aesthetic but his entire approach to storytelling. His fearlessness extends to content—he doesn't shy away from sex, violence, cruelty, or the grotesque but instead leans into these elements, forcing audiences to confront what they'd rather ignore.

As an absurdist, Lanthimos refuses to look away from the mess humanity has created. He highlights our frailties and insecurities, our remarkable ability to complicate everything. His films serve as forensic examinations of human failure, with conclusions so horrifying they become inevitably hilarious. We find ourselves entertained while simultaneously reckoning with the realization of being laboratory rats—and not particularly competent ones at that.

Lanthimos uses cinema to emphasize that tragedy isn't always noble or redemptive—it's simply what occurs when flawed creatures refuse to learn. In his cinematic universe, everybody hurts, and that universal pain becomes both the subject and the punchline.