The Physical Life of Words: Uncovering Hindi's Material Past

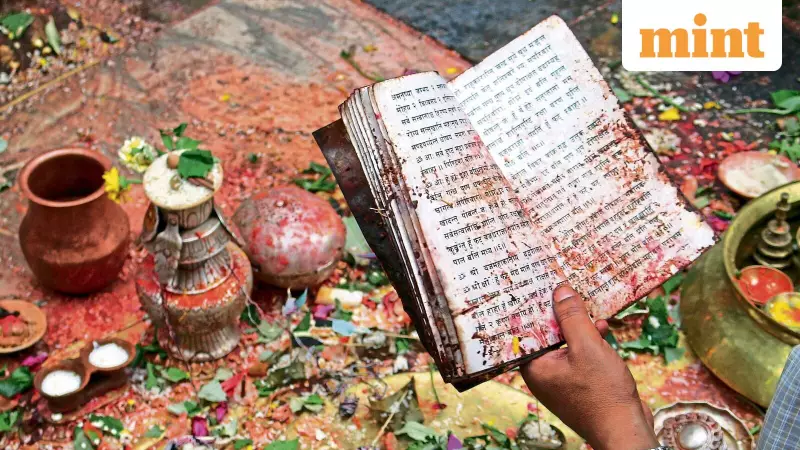

For students at an Arya Samaj school in Ranchi, Saturday mornings meant participating in a traditional havan ceremony. One curious student once peeked into the teacher's book and made a fascinating discovery. Instead of a printed text, it contained handwritten mantras with colloquial Hindi instructions for emphasis and tone, revealing how the physical form of texts carries meaning beyond their words.

This personal anecdote opens a window into the central argument of Tyler W. Williams' groundbreaking book "If All the World Were Paper: A History of Writing in Hindi." The physical form of books and the social circumstances of their production play a crucial role in understanding Hindi's evolution as a language.

The Making of Modern Hindi: Political and Cultural Forces

As Williams demonstrates, Hindi publishing as an organized industry is barely 100 years old. Its standardization emerged largely from the demand for a common language during India's freedom movement. These political necessities ultimately shaped Hindi into the versatile mass language we know today—capable of expressing poetry, politics, devotion, and even revolution.

The book reconstructs four distinct "scenes" of vernacular writing in early modern north India, examining how ideologies of writing, textual genres, and material artefacts formed organic wholes. Williams analyzes specific genres including the pem-katha (epic romance), pothi (scholastic book), gutaka (handwritten personal notebooks), and granth or vani (Sikh scriptures).

Multilingual Roots and Material Clues

In his examination of the pem-katha, Williams analyzes 14th-century poet Maulana Daud's epic Sufi romance "Candāyan" from 1379. Daud incorporated linguistic influences from Amir Khusrau's rekhta verses that mixed Hindi and Persian lines. This reflects the ideal of the polyglot emperor, well-versed in multiple languages including Sanskrit and Persian.

Scholars like Sheldon Pollock and Christian Novetzke identify this period as the beginning of the subcontinent's multilingual literary culture, propagated through Sultanate courts. Similarly, the chapter on the pothi reveals how 17th to early 19th century nirgun Bhakti writings created a new "written vernacular" that used Sanskrit phrases to evoke classical authority.

Williams pays particular attention to handwritten idiosyncrasies, noting how red ink was used for meta-textual commentary, continuing older traditions where texts were copied in multiple languages for different rulers. Premodern Hindi manuscripts contain unusually detailed meta-text, with various phrases describing the physical act of writing—racha (create), granth-bandh, gaanth (to tie)—each indicating different production methods.

Why Materiality Matters: From Samizdat to Gita Press

Williams employs three research methods: physical inspection of manuscripts, close reading, and "distant reading"—computer-led analysis of large text collections. This interdisciplinary approach allows him to track word frequency patterns and develop substantive hypotheses about literary evolution.

But why does studying the materiality of books matter? The answer becomes clear when examining historical examples worldwide. At the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights in Vilnius, Lithuania, samizdat exhibits reveal how banned publications were produced under Soviet regimes—handwritten texts hidden in bindings, encrypted newspaper passages, and invisible ink all tell stories of political resistance.

Closer to home, Akshaya Mukul's "Gita Press and the Making of Hindu India" demonstrates how the Gorakhpur-based publisher shaped Hindu consciousness among north Indian middle-class families. Similarly, Aakriti Mandhwani's research shows how Hindi magazines like Sarita and Dharmyug in the 1940s influenced post-independence middle-class aspirations.

For contemporary historians, reading the words alone is insufficient. One must investigate the economics of production, examine ink, typeface, binding, and other publishing accoutrements. A book remains a physical artefact, and upon its body lies imprinted the story of its life—waiting for persistent researchers to connect the dots and reveal the secret history of how we write and read.