For 136 years, the identity of Jack the Ripper has remained one of history's most chilling unsolved mysteries. The shadowy figure who terrorised London's Whitechapel district in the autumn of 1888, brutally murdering at least five women—Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly—vanished without a trace, leaving behind a puzzle that continues to captivate and frustrate.

The Controversial Shawl and the DNA Claim

In 2007, a London businessman named Russell Edwards purchased a piece of fabric he believed was a shawl from the murder scene of Catherine Eddowes, the Ripper's fourth victim. Edwards later claimed that advanced DNA analysis on the shawl revealed genetic material linked to Eddowes and, crucially, to a living relative of Aaron Kosminski, a Polish immigrant who was a prime suspect for Victorian police in 1888. Edwards presented this as definitive proof in his 2014 book, Naming Jack the Ripper, arguing the DNA match solved the case.

However, the scientific community greeted these claims with immediate and deep scepticism. When experts requested the technical data behind the DNA analysis, they found no hard data or published methodology to review. While more information surfaced in 2019, including a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) link to a Kosminski relative, experts like Hansi Weissensteiner clarified its limitations. "Mitochondrial DNA isn't a fingerprint," he explained. It is a broad genetic marker shared by potentially thousands of people, meaning it cannot pinpoint a single individual like Aaron Kosminski.

Why Experts Are Not Convinced

Forensic and historical criticisms of the shawl evidence are extensive. Firstly, the authenticity of the shawl itself is questionable. Having passed through countless hands over 137 years, the potential for contamination is enormous. Forensic DNA interpretation expert Jarrett Ambeau emphasised that the science cannot determine when the DNA was deposited or by whom.

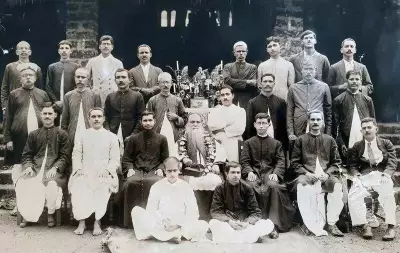

Furthermore, the choice of Aaron Kosminski as the suspect is not new. He was already on the police radar in 1888—a Whitechapel resident with mental illness who was later institutionalised. While some officers privately suspected him, the evidence was always circumstantial. The shaky DNA from the shawl does nothing to strengthen that old theory.

A Mystery That Refuses to Die

The Ripper case, lacking preserved physical evidence and reliable witnesses, seems destined to remain open. Its enduring appeal lies in the vacuum of certainty, which invites endless speculation. Just last year, author Sarah Bax Horton proposed a completely different suspect: Hyam Hyams, an epileptic and alcoholic cigar maker from Whitechapel. In her book, she argues that witness descriptions align with Hyams' physical impairments.

This cycle of new "solutions" only highlights the case's ultimate unsolvability. From local criminals to royalty, the list of accused is long and varied. The name "Jack the Ripper" itself originated from a likely hoax letter sent to the press, cementing a sensational myth that outlived the facts.

While the quest to name the killer is a macabre fascination, the truth is that Jack the Ripper has transcended a historical criminal to become an enduring story—a dark legend stubbornly resistant to a final chapter. Edwards may believe he has his man, but science and history insist the fog of Victorian London still hides the real answer.