In the heart of Rajasthan, a silent cultural erosion is taking place. Mandana, a centuries-old ritual floor art form, is battling for its very existence, caught between the march of modernity and fading collective memory. At 74, artist Vidya Devi Soni from Bhilwara stands as a passionate guardian of this tradition, her life's work a poignant window into a world where art was not decoration but a sacred language marking life's milestones.

More Than Floor Decoration: A Ritual in Red and White

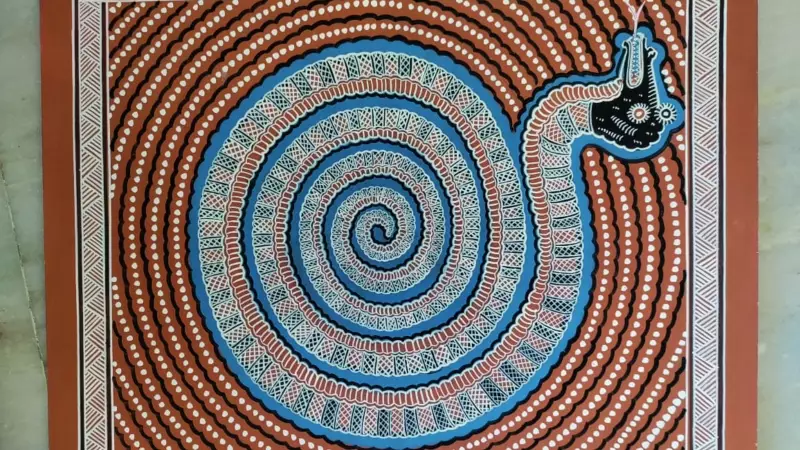

To the untrained eye, Mandana might resemble a rangoli. But as Vidya Devi Soni emphatically clarifies, the difference is profound. Mandana is a ritual art, traditionally created on freshly plastered mud floors using only natural pigments: geru (red-brown earth) and khadiya (white clay). Its purpose was never merely ornamental.

"It marked life itself," Vidya explains. From Diwali and seasonal changes to marriages and childbirth, specific Mandana designs appeared on household floors as expressions of belief, protection, and continuity. When a bride entered a new home or a daughter visited her maternal house, the floor would tell the story through symbolic motifs—chariots, birds, cows, lamps—each with a strict name and purpose passed down through generations.

"I learned it from my mother. In those days, every house in Bhilwara made Mandana. It was part of daily life," she recalls with nostalgia. Today, that ubiquitous practice has shrunk to a handful of families like the Sonis, who remember its true significance.

Concrete Floors and a Crisis of Identity

The decline of Mandana is intrinsically linked to the disappearance of its canvas: the kuchcha (mud) house. The rough, absorbent mud floors, smeared with a mix of soil and cow dung, allowed the natural pigments to merge and last for months. The shift to pucca (concrete) homes has been devastating for the art form.

"On concrete, the art is swept or washed away in a day. It has no permanence," laments Vidya. This physical displacement was accompanied by a cultural one. The art form began to be confused with the more decorative, commercially-driven rangoli, which uses bright, readymade powders and lacks the embedded ritual symbolism.

"People like it, they admire it, but they don't really understand it," says Vidya. "They don't know why it was made, on which occasion, or what each design symbolised." This loss of meaning, coupled with the convenience of ready-made stickers and stencils, has pushed Mandana to the margins.

Adapting to Survive: From Floors to Canvas Walls

Confronted with this existential threat, Vidya and her son, Dinesh Soni—a Pichwai artist by profession—made a strategic decision. To ensure survival, they adapted the medium but staunchly preserved the method and meaning. Mandana has now moved from ephemeral floors to permanent surfaces like cotton cloth and hard sheets.

"The art form is the same," Vidya insists. "Only the surface has changed." These portable works serve as wall art, allowing urban audiences in cities like Mumbai, Surat, and Delhi to engage with the tradition. Dinesh notes a growing, curious interest, with learners from Gen Z seeking rooted, meaningful connections to heritage.

However, challenges persist. Teaching Mandana online is difficult, as the art relies heavily on physical demonstration, texture, and the feel of natural materials. "It doesn't translate easily to a screen," Dinesh admits.

A Quiet Resistance Awaits Recognition

Despite its deep cultural value, Mandana remains largely unrecognized and unsupported at an institutional level. Dinesh Soni reveals that while surveys were conducted and questions were raised in Parliament about classifying it as an endangered art form, no concrete protective measures or sustained government support ever materialized.

"If this continues, many such arts will simply vanish," he warns. The Soni family's work is thus a quiet, resilient resistance. They are not just preserving a museum piece; they envision a living tradition. "We don't just want to preserve it," Vidya states. "We want it to travel. We want young people to learn it, earn from it, innovate with it—without losing its soul."

Mandana's strength, as Vidya points out, was its universality. It wasn't tied to a single caste or community but was once a shared visual language known in every household, much like mehendi. Its potential disappearance represents not just the loss of an art form, but the fraying of a cultural thread that wove together ritual, memory, and identity for generations in Rajasthan.