Sagada's Cliff Coffins: The Igorot Tradition of Hanging the Dead for 2,000 Years

Death is the universal human experience that every culture acknowledges, yet the ways in which societies bid farewell to their loved ones vary dramatically across the globe. While some traditions involve quiet burials beneath orderly rows of gravestones, others return bodies to fire, rivers, or faith-based rituals. Despite these differences, each farewell is imbued with common emotions: love, grief, and a hopeful belief that death is not the final end. In a small mountain town in the Philippines, however, death takes a form so unique that it leaves an indelible impression on all who witness it.

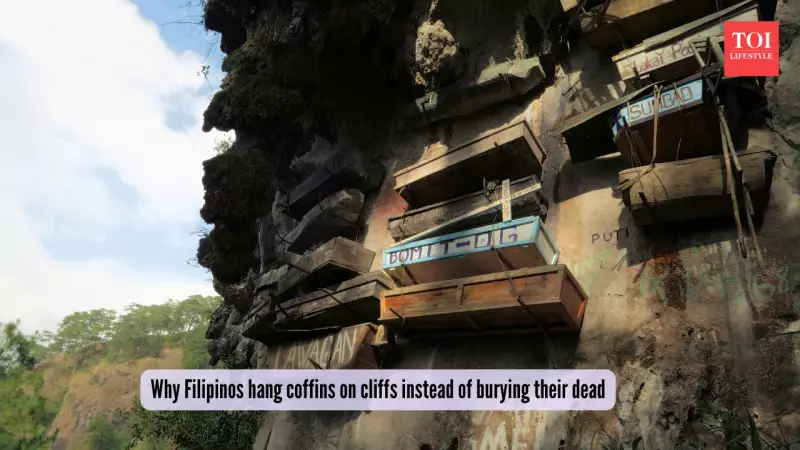

The Unforgettable Sight of Hanging Coffins

High in the cliffs of Sagada, nestled within the Cordillera mountains of northern Luzon, the Igorot people practice a burial method that defies conventional expectations. Here, coffins are not laid to rest underground; instead, they hang from sheer rock walls, clinging to the cliffs like birds' nests. These tiny wooden caskets, secured by nails, vines, and centuries-old tradition, have been part of this community's way of life for over 2,000 years. To visitors, the sight of weather-beaten coffins dotting the rugged landscape is both strange and profoundly moving—a quiet, haunting reminder of a different approach to mortality.

A Journey to Sacred Ground

Reaching Sagada is an adventure in itself, involving an eight-hour drive from Manila through narrow, winding roads that eventually open up to reveal the majestic mountains. When the cliffs come into view, adorned with these ancient coffins, the experience is arresting. For the Igorot, particularly the Kankanaey people who call this region home, there is nothing unusual about this practice. This is sacred ground, where burial traditions are deeply intertwined with spiritual beliefs and a connection to the natural world.

Why Cliffs Instead of Ground?

The choice to hang coffins on cliffs stems from practical and spiritual reasons. The Igorot believed that burying bodies in the earth exposed them to water, animals, and decay, making cliffs a safer, higher alternative. More importantly, elevation held symbolic significance: the higher the coffin, the closer the soul was to immortality and the ancestors. As local guide Bangyay once explained, this practice mirrors a return to the beginning—the body is folded into a foetal position, symbolising rebirth and readiness for the next journey. This belief in death as a crossing, rather than an end, finds echoes in other global customs, such as tree burials in Indonesia or dances with the dead in Madagascar.

The Rituals of Mourning and Placement

When an Igorot passes away, mourning begins with a gathering of families that lasts for days. Feasts are prepared, often involving pigs and chickens—three pigs and two chickens for elders—as part of the ceremonial offerings. The body is placed upright on a special chair called the sangadil, facing the doorway as if awaiting a final journey. Wrapped in blankets and tied with rattan vines, it is slowly smoked to delay decay and reduce odour, while relatives maintain a vigil.

One of the most surprising aspects for outsiders is the preparation of the body: the bones are gently broken to allow it to be curled into a foetal shape, compact enough to fit into a coffin barely a metre long. Young men then undertake the perilous task of climbing the cliffs with ropes and nails to fix the coffin high above the valley floor. Vines are used to seal it in place, and mourners often reach out to touch the procession for luck, with some even allowing funeral fluids to fall on them, believing it brings blessings.

A Living Reminder of Life and Death

Near the hanging coffins, wooden chairs sometimes dangle beside them, serving as personal signs and quiet reminders of lives once lived. In a world where death is often concealed behind hospital walls or polished marble monuments, Sagada offers a rare, open display of mortality. It approaches death spiritually and meaningfully, showing that the departed are not hidden away but elevated—watching from the cliffs, closer to the sky and ancestors. This ancient tradition underscores that even in death, there are endless, beautiful ways to honour life, preserving a cultural heritage that continues to inspire awe and reflection.