As auction prices for Raja Ravi Varma's paintings reach unprecedented heights, a renewed appreciation is emerging for the work of his largely forgotten son, Rama Varma Raja. This revival strangely mirrors the complex dynamic the two artists shared during their lifetimes, with the son forever working in the shadow of his legendary father.

The Promising Heir

In 1907, barely a year after the death of the celebrated Raja Ravi Varma, the Madras press was already praising another artist bearing the same prestigious last name. The Patriot newspaper observed that while the nation mourned Ravi Varma's passing, it was a source of genuine pleasure that he had left behind an heir who, despite his youth, had demonstrated brilliant possibilities with his inherited brush.

Several years later, The Hindu would note that this younger Varma displayed the same perfect drawing, wealth of imagination, and profusion of color in his canvases as his famous father. The publication declared that the mantle of Ravi Varma had surely fallen on the son.

Rama Varma Raja (1880-1970) represented perhaps the first instance of a nepo baby in India's art scene. On the surface, his life appeared to be one of pure privilege and powerful connections. His father was a popular figure across colonial India with access to everyone from British viceroys to nationalist leaders. Through his mother, Mahaprabha, Rama Varma was descended from royalty and was nephew to the maharani of Travancore.

A Life Behind the Glamour

Despite the aristocratic appearances, Rama Varma's life contained significant struggles and smudges. He was born at a time when his father's career was taking off, meaning Ravi Varma was frequently away from home due to his extensive travels. His parents had a tempestuous marriage, with his mother described by one relative as a great drunkard.

The family history included unusual dramas—one of his grandfathers in the 1860s was involved in a criminal case involving a jackfruit as a murder weapon, an incident that attracted newspaper attention as far away as Britain. Rama Varma also witnessed his own brother succumb to alcoholism; this sibling vanished in 1912 and was never heard from again.

Unlike his primarily self-taught father, Rama Varma received formal training at the Sir JJ School of Art in Bombay, followed by studies at the Madras School of Art. This educational path came with its own complications, as his elite milieu frowned upon men of their class pursuing painting as a vocation rather than a hobby.

An 1899 diary entry by his uncle reveals that the boy's aunt, the Travancore maharani, was greatly annoyed at his resolution to give up his studies and dedicate himself to painting. Even within his family, Ravi Varma was not universally seen as a role model for his own son.

Forging His Own Path

Defying these pressures, by his twenties, Rama Varma began occasionally traveling and painting with his father. Genuine affection existed between the two, and Ravi Varma felt particular anxiety about his son's fragile health—Rama Varma was asthmatic and suffered a life-threatening attack of dysentery that caused grave concern.

The younger Varma recovered and in the last two years of his father's life became his primary assistant. He was present when Ravi Varma completed his final set of paintings for the Maharajah of Mysore. Then in 1906, when Rama Varma was just 26, his illustrious father died, leaving the son to craft his artistic reputation independently.

Initially, the Varma brand proved helpful. As Sharat Sunder Rajeev, author of the forthcoming book The Forgotten Atelier: Painters, Patrons, and the Artistic Legacy of the Travancore Court notes, The Ravi Varma tag was very important for Rama Varma. This wasn't mere careerism—there was an entire circle of Ravi Varma's disciples who took pride in that association.

Royal clients were generous to Rama Varma in the early years, with commissions from durbars in Baroda and Rewa. For some years through the 1910s and 1920s, he painted pictures based on epics and Sanskrit literature, including scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata.

He not only pursued his father's style but sometimes incorporated actual figures from Ravi Varma's canvases into his own works, subtly suggesting continuity. He also made copies of his father's work—including Ravi Varma's Aja's Lament—that were nearly indistinguishable from the originals.

The Changing Tides of Indian Art

Despite his skill and promising beginnings, Rama Varma would never achieve his father's pan-India celebrity. One significant factor was timing—Ravi Varma's death coincided with Indian nationalism assuming a more aggressive form. In this age of swadeshi, Western influences in art became increasingly resented.

It no longer mattered if artists painted Indian themes; if they practiced academic realism and European oil painting techniques, they were viewed with suspicion. Rama Varma seemed aware of this shift, with his son later writing defensively about how the artist never cared to paint pictures for pleasing anybody or for acquiring popularity.

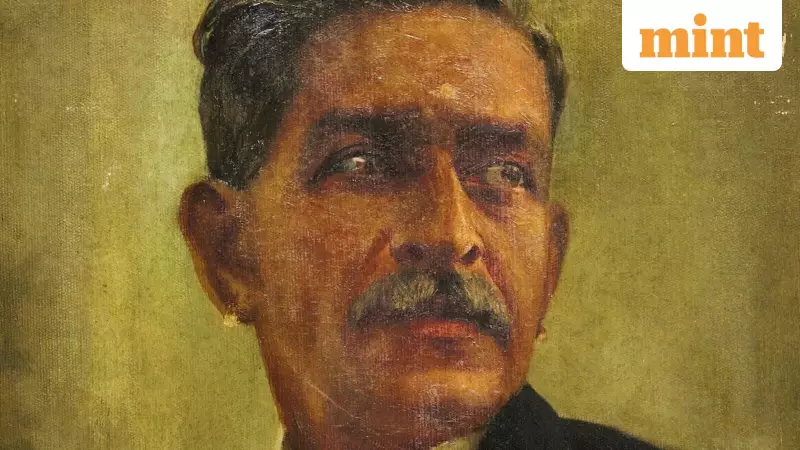

Where Rama Varma truly excelled was in portraiture. Several of his portraits hang in the collection of the Kerala Museum in Kochi, depicting subjects ranging from judges to friends in traditional dress. He was also a skilled photographer who held a franchise from Kodak to sell camera equipment, and many of his portraits were created from photographs rather than live sittings.

Despite being largely forgotten outside Kerala, Rama Varma kept the flame of his father's artistic style alive in his home state. He established the Ravi Vilas Studio, which became the cradle for several generations of Malayali artists. His financial security allowed him to paint as he wished, ignoring emerging avant-garde trends.

In the 1930s, while India was discovering artists like Amrita Sher-Gil, Rama Varma traveled to Europe to study Renaissance masters. The establishment continued to respect him—in 1921 he served on a committee to reorganize his alma mater in Madras, and in the 1960s he headed the Kerala Lalithakala Akademi.

Rediscovery and Legacy

Today, renewed interest is growing in Rama Varma's work. One reason is that his paintings now hold historical significance, and the nationalist anti-Western sentiment that once marginalized him has faded. Market dynamics also play a role—with Ravi Varma's works becoming prohibitively expensive (his Mohini sold for nearly ₹20 crore in 2024), collectors with smaller budgets are looking at other artists from the Varma circle.

Rama Varma has become an attractive alternative—his painting of Shakuntala sold for just over ₹2 crore in 2021. In this sense, the artist continues to exist in his father's shadow, a position he likely wouldn't have minded given his career choices and arc.

One of his last paintings was a copy of Ravi Varma's Mahananda. Created in 1968 when the artist was elderly, the work lacks some intricate details present in the original, including the garden background. Most tellingly, as Rama Varma explained to the painting's recipient, his shaking hands prevented him from painting the strings on the veena.

The signature at the bottom of the canvas perfectly encapsulates the artist's entire career: After Ravi Varma, Rama Varma. This simple inscription acknowledges both his artistic debt and his permanent position in relation to his legendary father, whose shadow he both worked within and contributed to throughout his long and complex artistic journey.