For decades, the story of early human weaponry was told as a simple, step-by-step progression. The narrative suggested our ancestors first used basic handheld spears, then invented spear-throwers for greater range, and finally mastered the bow and arrow much later. However, groundbreaking new research is shattering this linear timeline, painting a picture of early Homo sapiens as versatile engineers who likely used multiple weapon systems simultaneously.

Rethinking the Linear Progression of Ancient Arms

A major study led by researcher Keiko Kitagawa from the University of Tübingen is challenging long-held archaeological beliefs. Published on December 18 in the journal iScience, the research argues that hunting technologies did not develop in a straightforward sequence. Instead, early humans in Europe were experimenting with complex systems, including bow-and-arrow technology, far earlier than previously documented.

The biggest hurdle for archaeologists has always been the scarcity of direct evidence. Most prehistoric hunting tools were crafted from organic materials like wood and sinew, which decay over millennia. What survives are usually just the stone, bone, or antler tips—mere fragments of a larger, sophisticated technological kit.

A New Method: Reading the Story in Fractures

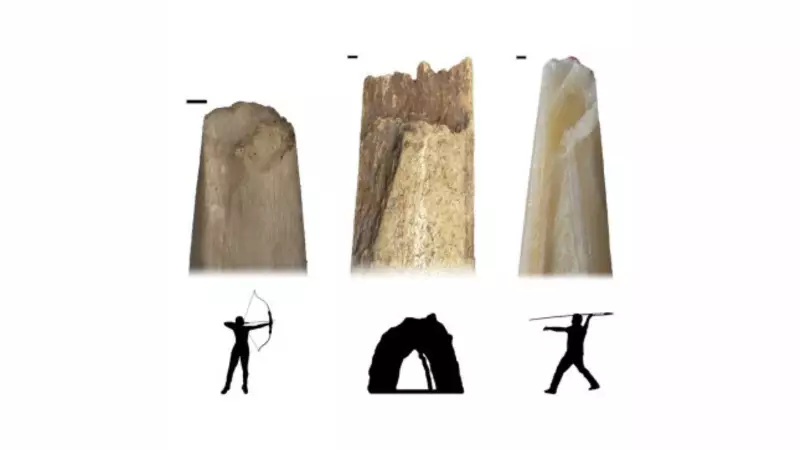

Since complete ancient weapons are rare, Kitagawa's team adopted an innovative approach. They focused on analysing the damage and fracture patterns on surviving projectile points, primarily those made from antler and bone from the Aurignacian period (40,000 to 33,000 years ago).

The researchers created replica points and launched them using different weapons—thrusting spears, spear-throwers, and bows. By comparing the resulting impact marks and breakages with those found on genuine archaeological artefacts, they could infer the likely launching mechanism. Their findings revealed specific fracture signatures that strongly suggest the use of bows and arrows during the Upper Palaeolithic era in Europe.

This pushes back the timeline for bow use significantly. Previously, the earliest clear evidence in Europe came from sites like Mannheim-Vogelstang and Stellmoor in Germany, dating to about 12,000 years ago, and Lilla Loshults Mosse in Sweden from roughly 8,500 years ago. In contrast, the earliest known wooden spears in Europe are much older, dating back 337,000 to 300,000 years.

Implications: Early Humans as Adaptive Hunters

This research fundamentally changes our understanding of prehistoric ingenuity. It indicates that early humans were not slowly progressing from one technology to the next. They were likely pragmatic and adaptive, employing a "multi-tool" arsenal suited to different prey, terrains, and situations. A hunter might carry a thrusting spear for close encounters, a spear-thrower for medium-range game, and a bow for silent, long-distance strikes.

The study underscores the complexity of reconstructing ancient life from partial evidence. Factors like the raw material's properties, the angle of impact, and post-depositional damage all influence how a point breaks. By moving the focus from hunting for intact artefacts to meticulously analysing microscopic wear and tear, archaeologists can extract far more information from the existing record.

This revelation places early Homo sapiens in Europe as highly capable and innovative engineers much earlier in our shared history. It dismantles the outdated idea of linear progression and replaces it with a dynamic portrait of versatile problem-solvers, expertly crafting and using a suite of technologies to thrive in a challenging world.