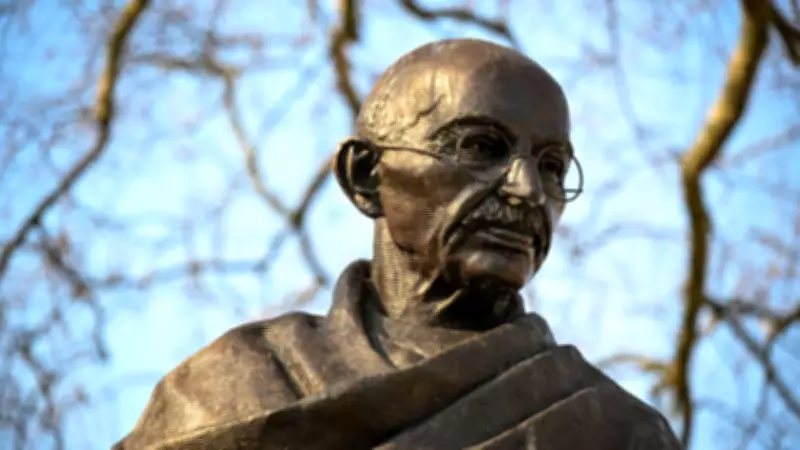

The Nobel Peace Prize's Most Puzzling Omission: Mahatma Gandhi

It is frequently stated that the most significant oversight in the history of the Nobel Peace Prize is Mahatma Gandhi. The common belief is strong: a worldwide ambassador of non-violence, nominated on multiple occasions, was refused recognition by a cautious or politically hesitant committee. In public consciousness, this narrative has solidified into a moral shortcoming. Gandhi represents the twentieth century's ultimate symbol of peace; the Nobel Committee seems to have overlooked the apparent candidate.

The Educational Paradox: Classroom Teaching Versus Institutional Recognition

For numerous students learning about Gandhi in their textbooks, this exclusion appears even more perplexing. School syllabi frequently portray him as the quintessential figure of non-violent opposition in contemporary history. When pupils discover that he never obtained the Nobel Peace Prize, their response is typically one of astonishment. The disparity between educational instruction and formal institutional acknowledgment becomes a subject of intrigue and occasional silent bewilderment.

Nevertheless, the historical documentation challenges that straightforward conclusion. Gandhi was not disregarded. He received five nominations. He underwent thorough assessment. He was included on shortlists. The factors preventing his receipt of the award were neither trivial nor exclusively political. They originated from the Nobel Committee's interpretation of "peace work," its understanding of Alfred Nobel's testament, and its evaluation of Gandhi's political function during periods of severe turmoil. The conflict exists not between excellence and ignorance, but between public symbolism and institutional benchmarks.

The Public Perception: A Logical Laureate Denied

The widespread account proceeds as follows: Gandhi introduced satyagraha, organized millions without promoting armed rebellion, suffered incarceration, and motivated movements ranging from the American civil rights struggle to anti-colonial initiatives globally. His murder in 1948 established his position as a peace martyr. The Nobel Peace Prize, created to acknowledge endeavors promoting brotherhood among nations and decreasing military confrontation, should rationally have acknowledged him.

In hindsight, the reasoning seems undeniable. Gandhi's ethical standing is seldom contested. Subsequent Nobel representatives personally conveyed remorse that he was never honored. In 1989, when the Dalai Lama obtained the Peace Prize, the committee chairman characterized the award as partially an homage to Gandhi's legacy. Such declarations strengthened the view that a historical mistake had transpired.

However, the committee that evaluated Gandhi functioned within an alternative conceptual structure.

The Institutional Challenge: A Mismatch of Templates

Until the mid-twentieth century, the Nobel Peace Prize was granted mainly to European and American diplomats, legal experts, humanitarian coordinators, and designers of international law. Recipients generally operated via treaties, arbitration systems, relief agencies, or cross-border organizations. The prize mirrored a liberal internationalist custom based on legal formalism and organized diplomacy.

Gandhi did not conform to this model. He was not a state mediator. He did not establish international legal structures. He did not head a worldwide entity dedicated to conflict resolution. He was the pivotal personality in a national liberation movement opposing British colonial authority.

This differentiation was significant. To many supporters, India's fight for independence personified the ethical rationale of peace. To the committee, though, anti-colonial nationalism prompted inquiries. Was a freedom campaign, even one founded on non-violence, comparable to international peace endeavors? Could a leader involved in direct opposition to a colonial power be appraised separately from the political outcomes of that struggle?

The committee's internal documents indicate prudence rather than antagonism. In 1937, advisor Jacob Worm-Müller recognized Gandhi's moral integrity but depicted him as a multifaceted political participant. He mentioned what he perceived as contradictions and the potential that non-violent initiatives might incite violence among adherents. Such remarks did not reject Gandhi's dedication to non-violence. They demonstrated anxiety about accountability in mass movements.

The Nobel Committee was not appraising Gandhi as an emblem. It was examining him as a political leader whose campaigns developed in unstable circumstances.

The Evidence Conundrum: Outcomes and Ambiguity

A repeated criticism during Gandhi's early nominations involved the connection between his philosophy and its results. Satyagraha required disciplined non-violence and acceptance of legal penalties. Yet specific campaigns, particularly throughout the Non-Cooperation Movement, witnessed instances of crowd violence. Opponents contended that widespread civil disobedience could not be shielded from disorder.

The committee's consultants did not charge Gandhi with supporting violence. They doubted whether his techniques could dependably avert it. In the interwar era, pacifism was frequently characterized in absolute terms. Any uncertainty caused discomfort.

An additional matter was the extent of Gandhi's activism. Some examiners questioned whether his initiatives were chiefly national instead of universal. In South Africa, he championed Indian rights, not for the wider African community. Within India, his main goal was independence. For the committee, whose mission stressed fraternity among nations, the difference between national liberation and international harmony was notable.

These concerns do not invalidate Gandhi's accomplishments. They clarify the standards employed by assessors working within a particular institutional environment.

1947: The Critical Juncture

By 1947, India had gained independence. Gandhi's reputation was at its zenith. Yet independence occurred simultaneously with partition and extensive communal violence between Hindus and Muslims. Hundreds of thousands perished. Millions were uprooted.

The Nobel Committee reviewed Gandhi again that year. Two members favored granting him the prize. Three objected. Their reluctance arose from the continuing conflict between India and Pakistan and from public remarks Gandhi had delivered concerning the possibility of war if justice could not be ensured.

Although Gandhi explained that he personally remained devoted to non-violence, the context was crucial. The committee confronted a predicament. To bestow the prize on a figure linked to one side of a recently divided subcontinent, amid active hostilities, risked seeming biased. The prize had not earlier been utilized as a tool to affect unfolding regional disputes.

Ultimately, the committee presented the 1947 Peace Prize to the Quakers. The choice indicated caution rather than rejection.

1948: The Procedural Limitation

Gandhi was assassinated in January 1948, shortly before the nomination deadline. He was nominated once more that year. The committee placed him on its shortlist and contemplated the option of a posthumous award.

Here the hindrance was procedural. No Peace Prize had been awarded posthumously. Gandhi did not belong to an official organization that could accept the prize on his behalf. He left no will specifying recipients. Advisors consulted other Nobel-awarding bodies, which advised against posthumous acknowledgment unless death happened after the decision.

In November 1948, the committee announced that there was "no suitable living candidate." No prize was awarded that year.

Looking back, it seems probable that had Gandhi survived longer, he would have received the honor. But institutional regulations restricted the committee's alternatives at that time.

Public Acclaim Versus Expert Judgment: A Broader Phenomenon

The divergence between public anticipation and committee analysis demonstrates a wider occurrence. Public admiration tends to solidify around ethical narratives. Expert judgment functions within codified mandates, precedents, and interpretive traditions.

By the late twentieth century, the Nobel Peace Prize broadened its conceptual limits. It acknowledged human rights advocates, environmental activists, and leaders of non-violent resistance. In that expanded structure, Gandhi appears an undeniable laureate.

In the 1930s and 1940s, however, the prize's criteria were more confined. Anti-colonial movements were not automatically equated with international peace endeavors. Pacifism was assessed through rigorous lenses. Political involvement in active conflicts produced caution.

The omission reflects institutional traditionalism rather than mere neglect.

What This Genuinely Discloses: Evolving Recognition and Institutional Norms

The instance of Gandhi reveals how acknowledgment progresses alongside institutional standards. It emphasizes that awards do not simply reward moral eminence; they codify specific interpretations of peace at distinct historical moments.

Gandhi's impact did not rely on Nobel endorsement. His methods transformed political opposition globally. Yet the Nobel Committee's hesitation reveals the tension between emerging forms of political action and established evaluative frameworks.

Historical judgment tends to reduce complexity into conclusions. The archival record opposes that reduction. It displays deliberation, uncertainty, and adherence to procedural limits. It shows a committee struggling with categories that were changing under the strain of decolonization and global conflict.

The wider lesson is not that institutions are inevitably myopic. It is that institutions mirror the intellectual boundaries of their era. As those boundaries expand, earlier decisions can appear limited. Recognition follows interpretation, and interpretation is historically situated.

Gandhi's absence from the list of Nobel laureates has become symbolic. Yet the narrative is less about a moral deficiency than about the developing definition of peace itself. What constituted peace work in 1937 or 1947 was not identical to what constitutes it today.

The misunderstanding endures because hindsight clarifies what contemporaries could not entirely perceive. Gandhi's legacy has expanded beyond the political contingencies that complicated his candidacy. The Nobel Committee's framework has widened beyond the legalistic tradition that once molded its selections.

In that divergence lies a lasting insight: moral authority and institutional recognition do not always coincide in real time. They align gradually, as standards evolve and categories broaden. History does not merely record greatness. It also records the confines within which greatness is assessed.