The Crushing Burden on Delhi's Court Ahlmads: Nightmares, Suicides, and a Cry for Relief

In the heart of Delhi's bustling judicial system, an ahlmad—a keeper of court records—paints a harrowing picture of overwork and despair. "I have nightmares about files… I can't even sleep properly," she confesses, her voice echoing the trauma faced by many in this critical cadre. This middle-aged professional, who wishes to remain anonymous, starts her day at 9 am, hauling piles of files from a cramped, cubbyhole-sized room just to make space to sit. The room, meant for two ahlmads, is so packed with files, a desk, a computer, a printer, a chair, and three almirahs that it barely accommodates one person.

The Nerve Centre of Judiciary Under Strain

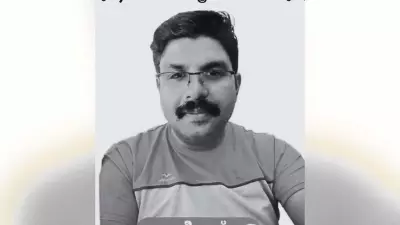

Ahlmads serve as the nerve centre of the judiciary at the district level, tasked with maintaining records of all files, preparing reports on pending cases for the Delhi High Court, and filling in for court readers and stenographers on leave. However, the burden has become overwhelming. Harish Singh Mahar, a 43-year-old ahlmad, tragically jumped to his death on January 9 at the Saket courts complex, leaving a note citing his 60% disability and unbearable work pressure. Mahar was posted at a digital traffic challan court with about 9,000 pending cases, where each of the two digital traffic courts in Saket handles an average of 300 cases daily.

Protest and Judicial Response

Following Mahar's suicide, court staff staged protests, drawing attention to the systemic issues. In response, the Delhi High Court acknowledged on Wednesday that it is "conscious" of the need to fill numerous vacancies for clerk posts in district courts, awaiting an audited report on vacant positions and required workforce strength. The woman ahlmad reflects grimly on the situation: "Pehle log government job ke liye marte the, ab government job ko paane ke baad mar rahe hain (People would die for a government job, but now they're dying literally.)."

Daily Grind and Mounting Pressure

Her court alone has almost 34,500 pending cases. On a typical day, the causelist—the list of cases to be heard—contains 311 entries, with around 200 new cases registered daily through the e-filing portal. Ahlmads must review these, potentially transfer cases to other courts, and handle up to a hundred public queries from litigants and lawyers. "Each one of us is expected to do the work of dozens of people. It's insane," she laments. "If only I had a pension to fall back on, I'd have left long ago, I am so frustrated."

By 5 pm, as most day workers head home, her work intensifies, preparing for the 300-odd cases listed for the next day. Additional tasks include filing monthly pendency reports for the High Court and preparing replies under the Right to Information (RTI) Act. Her day often ends at 8 pm, totaling 11 grueling hours. Driven by Mahar's death, she recently requested a transfer, stating, "After seeing what Mahar was driven to, I could delay it no longer."

Statistical Insights and Systemic Shortfalls

Statistical reports reveal a stark reality: pending cases in Delhi's district courts have surged from 4.7 lakh in January 2005 to nearly 16 lakh in January 2026. Over the last seven years, pendency has increased by an average of 1.3 lakh cases annually, despite record disposals of older cases. Meanwhile, the sanctioned strength of court staff remains stagnant, with 733 of 4,011 posts for ahlmads, assistant ahlmads, and readers vacant, according to court staff associations.

In May 2025, leaves were cancelled to keep courts running, and in December 2024, circulars highlighted stenographer shortages—only 1,200 of 1,600 sanctioned posts are filled. Data from the National Judicial Data Grid shows that over 26,000 cases are heard daily by more than 700 trial court judges in Delhi, with each stenographer typing about 40 orders on average. This systemic strain underscores the urgent need for reform and support for those at the frontline of India's judicial machinery.