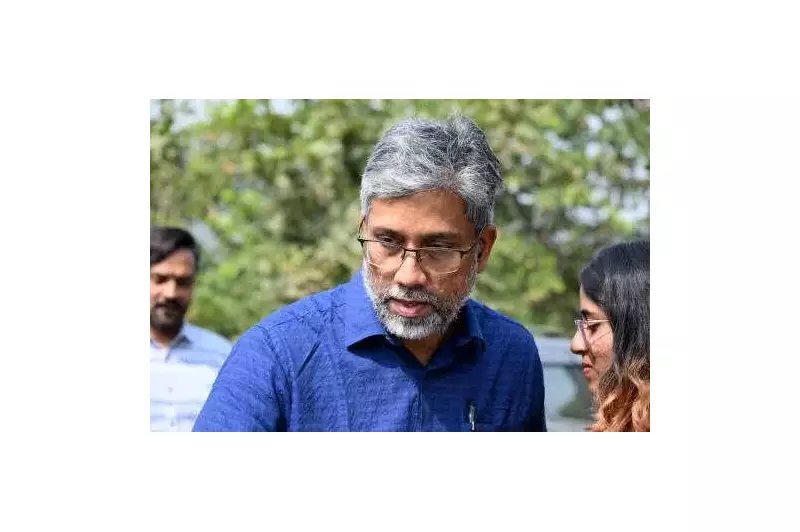

Two prominent academics, arrested in connection with the 2018 Bhima Koregaon case, have detailed the grim reality of India's prison system after spending years behind bars as undertrials without facing trial. Hany Babu, a Delhi University professor, entered Navi Mumbai's Taloja prison in July 2020 and was released on bail after five years. Scholar and writer Anand Teltumbde followed the same year and was released in 2022 after about two-and-a-half years of incarceration.

The Crushing Weight of Pre-Trial Detention

Their personal stories reflect a national crisis highlighted by the India Justice Report 2025. The report states that undertrials now constitute around 75% of India's prison population. By the end of 2022, a staggering figure of more than 11,000 prisoners had spent over five years in pre-trial detention, a number that has seen a steady rise over the past decade.

In conversations, Babu and Teltumbde painted a picture of life defined by interminable waiting for court dates that never arrived. Their days were governed by severely restricted communication with families, inadequate medical care, and an informal internal economy that dictated living conditions.

Overcrowding and the Illusion of Privilege

Babu was housed in a barrack officially meant for 22 inmates. "At no point during my stay was the occupancy less than 30," he revealed. "At one point, 60 prisoners were crammed into the 500 sq ft space." The most profound loss, he said, was the simple freedom to speak with loved ones. Phone access was ruthlessly rationed, often reduced to a single 10-minute call every 10 to 15 days, forcing heartbreaking choices between calling a wife or a mother.

Both men acknowledged a relative privilege due to their profiles, which spared them from the worst harassment. "Prison authorities dislike negative media coverage, so they mostly left us alone," Babu noted. However, he emphasized that this privilege merely meant receiving what was due by law. "Others are denied even that," he stated, pointing out that caste and class hierarchies from the outside world are meticulously reproduced inside prison walls.

Those without resources, Babu explained, routinely face denial of basic legal access or medical attention. "Some prisoners are inside for six or seven years without ever being produced in court. Families don't have the resources to visit, so they just rot," he said.

Medical Neglect and Systemic Indifference

The perilous state of healthcare became starkly clear when Babu developed a severe eye infection in May 2021. "I thought I would die there," he recalled. Prison authorities initially dismissed his condition, and the available doctor was an Ayurvedic practitioner unauthorized to prescribe needed allopathic medicine. Only after his situation deteriorated was he taken to Vashi Civil Hospital as an outpatient.

When antibiotics failed, authorities refused to readmit him, insisting he complete the course outside. He was finally moved to JJ Hospital only after his wife, professor Jenny Rowena, petitioned the Bombay High Court. "The doctor told me that any further delay would have spread the infection to my brain," Babu shared. He summarized prison medical care as "rock bottom," cynically observing, "No one dies in jail. They die on the way to hospital."

Controlled Communication and Human Adaptation

For Teltumbde, the most brutal deprivation was communication, exacerbated during the Covid-19 pandemic when newspapers stopped arriving. Phone access was tightly controlled in a manner he described as deliberately punitive. Inmates were marched to a phone room under the sun, a practice he labeled "absolute sadism" for a problem easily solvable with better management.

Reflecting on the human capacity to endure, Teltumbde recalled not eating or drinking for three days upon confinement. "Then they moved me to a private cell. I slept, ate, and told myself I could survive this," he said. His release on bail was met with scepticism, feeling he was being "moved from a small jail to a big jail."

In his 2025 memoir 'Cell and the Soul', Teltumbde describes a forced "humanitarian ethic" of sharing inside, but also reveals the prison as a plutocracy where money buys access, comfort, and influence. Wealthier inmates bypass canteen limits and build power networks, reinforcing social hierarchies instead of dismantling them. His pre-incarceration assumption that his stature would protect him proved utterly wrong.

The accounts of Babu and Teltumbde serve as a powerful indictment of a justice system where pre-trial detention becomes a punishment in itself, inflicted within overcrowded facilities that mirror and magnify the inequalities of the society outside.