Bengaluru Shifts to Paper Ballots for Municipal Elections

Bengaluru voters will mark paper ballots when they cast votes in the upcoming Greater Bengaluru Authority elections. The State Election Commission confirmed this decision on Monday. This move returns the city to traditional voting methods amid renewed political debate over electronic voting machines.

The change carries a quiet irony. Bengaluru first designed and built India's electronic voting machines. Now, the city will not use them in its own municipal elections.

The EVM Journey Begins in Bengaluru

The EVM story is closely tied to Bengaluru. Bharat Electronics Limited developed the devices here. These machines would eventually reshape India's entire electoral process. Yet, from their earliest trials, EVMs carried controversy alongside innovation.

Political parties across the spectrum have questioned EVM credibility at various points. They have also endorsed their use at other times. Concerns about EVM security actually date back to the late 1980s.

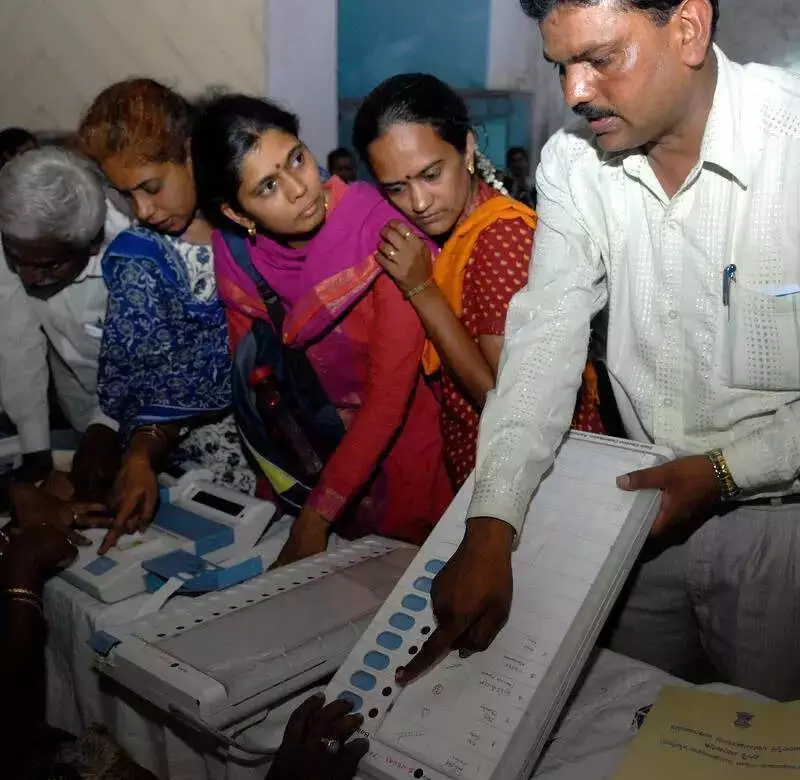

Colonel GK Rao laid the technical groundwork in Bengaluru. He served as director of research and development at BEL. Rao led development of a rudimentary EVM. The device was first tested successfully in trade union elections within the company itself.

Early Exploration and Implementation

RVS Peri Sastri first formally explored automating elections. He served as chief election commissioner from 1986 to 1990. Sastri studied election practices worldwide before making his proposal.

His approach was cautious. He wanted to modernize the ballot paper system while retaining the familiar act of voting itself. BEL subsequently produced about one hundred semi-production models.

These early EVMs were deployed in the 1986 Kerala assembly elections. The experiment was widely seen as successful. This success paved the way for important legislative changes.

With Sastri's backing and support from the law ministry, Parliament amended the Representation of the People Act. The amendment permitted the use of electronic voting machines in Indian elections.

A Key Safeguard Emerges

A crucial moment arrived in mid-1988. Then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi called for a live demonstration of the device. The presentation team included senior BEL officials and engineers.

Among them was the project head, software specialists, and the late Rangarajan. Readers might better know Rangarajan as the Tamil writer Sujatha.

Gandhi's response was not uncritical. He raised a practical concern rooted in electoral realities. Parts of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh experienced ballot-box snatching and rapid stuffing of votes.

His question was simple. Could the same be done with an electronic voting machine? His solution would ultimately shape the machine's design.

Gandhi suggested a mandatory time gap between successive button presses on the ballot unit. This change limited the speed at which votes could be cast. The design ensured no more than two votes could be polled per minute.

This safeguard reduced the scope for mass rigging even if a booth were briefly captured. With this feature incorporated, Gandhi announced that EVMs would be used in about thirty percent of constituencies during the 1989 general elections.

Political Resistance Follows

Political resistance followed swiftly. Opposition leaders including VP Singh and George Fernandes alleged that Congress intended to manipulate elections through software-controlled machines.

They staged a public demonstration using a general-purpose computer. The computer was programmed to produce incorrect results. Their argument claimed any electronic system could be tampered with.

Their specific claim suggested EVMs could be designed to divert votes to a particular party regardless of which button a voter pressed. In response, Gandhi constituted a high-level committee headed by LK Advani.

The committee's brief was clear. Test whether electronic voting machines could be manipulated. The panel included experts from IITs, the Institution of Electronics and Telecommunication Engineers, and DRDO.

They received just five days to attempt tampering with the machines. At IIT Delhi, a team led by Professor PV Indiresan worked continuously with advanced testing equipment and simulators.

Despite Indiresan's own view that any electronic device is theoretically hackable, the team failed to alter or manipulate the EVMs within the stipulated time. This exercise helped defuse immediate political opposition.

Large-scale production of indigenous electronic voting machines proceeded afterward.

The Current Irony

Over the decades, EVMs have become a fixture of Indian elections. Debates over their transparency and trustworthiness resurface periodically.

Ironically, those debates notwithstanding, Bengaluru has now reverted to paper ballots. The state election commission says its choice was backed by legislation and bereft of other considerations.

This leaves the city temporarily disconnected from a technology it helped create. That same technology continues to be used across much of the country today.