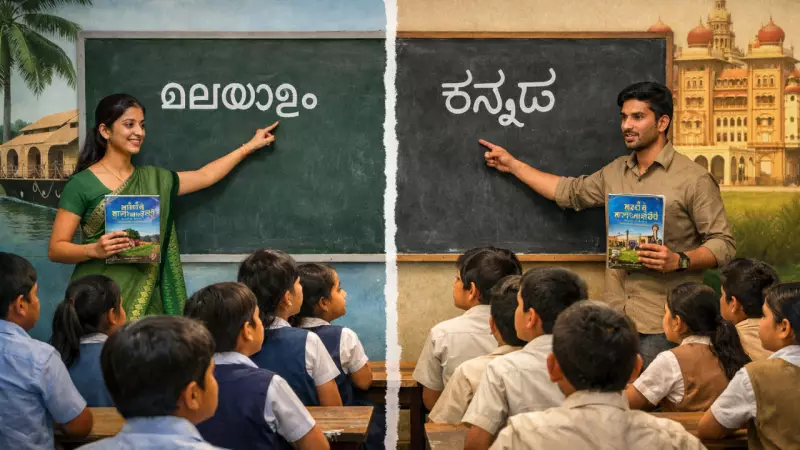

A proposed law in Kerala to strengthen the official status of Malayalam has escalated into an interstate schooling conflict, highlighting the complex realities of India's linguistic borders. The dispute centers not on the promotion of Malayalam within Kerala's heartland, but on its compulsory application in classrooms along the state's northern frontier with Karnataka.

Interstate Objections and the Core of the Bill

On January 9, 2025, Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah formally wrote to his Kerala counterpart, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, objecting to the Malayalam Language Bill passed by the Kerala Assembly. Siddaramaiah also urged Kerala Governor Rajendra Vishwanath Arlekar to withhold assent to the legislation. The Governor is now expected to review the Bill following objections from Karnataka’s Border Areas Development Authority.

The Bill, at its essence, performs two key functions. First, it formalizes Malayalam as Kerala's official language for all government business. Second, and more controversially, it mandates Malayalam as the compulsory first language from Classes 1 to 10 in schools. While the legislation includes a safeguarding clause for notified linguistic minorities like Kannada and Tamil, the practical enforcement in border regions has become the flashpoint.

Kasaragod: Where Policy Meets Ground Reality

The epicenter of the tension is Kasaragod, Kerala's northernmost district which shares a long border with Karnataka. Here, Malayalam is the official administrative language, but Kannada is woven deeply into the social and cultural fabric of many communities. For such border districts, a "first language" rule is never merely an academic decision; it is a policy that decides which linguistic identity becomes the default in the classroom.

Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan has dismissed Karnataka's concerns as "not based on facts," pointing to the Bill's inbuilt protections. Siddaramaiah, however, frames it as an attack on linguistic freedom, with Kasaragod as the primary example. This raises a critical administrative question: who bears the burden of invoking "safeguards" when the default rule is one of compulsion? A clause can promise protection, but a classroom has to live with its daily reality.

Beyond Symbolism: When Language Law Reorganizes Education

This episode stands out because it moves beyond symbolic pride to the reorganization of education. While states asserting linguistic identity is routine in India, it is unusual for one state to ask another's Governor to stop a law because it directly alters school curricula. The Bill shifts language from being a medium of administration to a foundational element of learning architecture.

The designation of a "first language" determines textbook ecosystems, teacher recruitment, assessment patterns, and the emotional ease with which a child engages with school. For a Kannada-speaking child in Kasaragod, this policy dictates what they must study, internalize, and be evaluated in during their formative years. Even with exemptions, compulsion often manifests through practical constraints: which languages schools are equipped to teach, which teachers are available, and which options the timetable prioritizes.

Karnataka's objection leans on constitutional safeguards. Articles 29 and 30 protect the rights of linguistic minorities, while Articles 350A and 350B obligate states to provide mother-tongue instruction at the primary level and to protect minority interests. The argument is that when a state law reorganizes the language of schooling in districts with recognized linguistic minorities, it enters territory the Constitution treats with significant caution.

A Recurring Indian Dynamic

India has witnessed similar tensions before. Kerala itself saw a previous Malayalam promotion Bill passed in 2015 languish without receiving assent. The state of Tamil Nadu famously rejected the national three-language formula in the 1960s, institutionalizing a two-language system to protect Tamil primacy in education, understanding how mandated languages reshape school systems over time.

Karnataka's own recent history is instructive. The state has made several attempts to make Kannada compulsory even in CBSE and ICSE schools, facing resistance from parents and legal scrutiny over state overreach into nationally affiliated boards.

Ultimately, border districts like Kasaragod expose what uniform laws often smooth over. Language here is not an abstract cultural marker but a daily negotiation affecting school admissions, teacher appointments, and a child's sense of belonging. The success of the Malayalam Language Bill's safeguards will not be measured by its careful drafting alone, but by how easily minority children and parents can navigate the education system without having to persistently claim their rights. In education, legitimacy is experiential—learned early and remembered long.